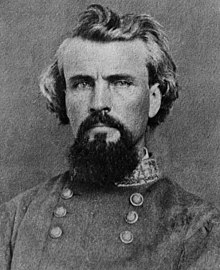

Nathan Bedford Forrest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Nathan Bedford Forrest |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Bed"[1] "Wizard of the Saddle"[2] |

| Born | July 13, 1821 Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | October 29, 1877 (aged 56) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Buried | Columbia, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Unit |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations |

|

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 – October 29, 1877) was a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War and later the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869.

Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth as a cotton plantation owner, horse and cattle trader, real estate broker, and slave trader. In June 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army and became one of the few soldiers during the war to enlist as a private and be promoted to general without previous military training. An expert cavalry leader, Forrest was given command of a corps and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle". He used his cavalry troops as mounted infantry and often deployed artillery as the lead in battle, thus helping to "revolutionize cavalry tactics".[3][4] While scholars generally acknowledge Forrest's skills and acumen as a cavalry leader and tactician, he is a controversial figure in U.S. history for prewar slave trading, his role in the massacre of several hundred U.S. Army soldiers at Fort Pillow, a majority of them black, and his postwar leadership of the Klan.

In April 1864, in what has been called "one of the bleakest, saddest events of American military history",[5] troops under Forrest's command at the Battle of Fort Pillow massacred hundreds of surrendered troops, composed of black soldiers and white Tennessean Southern Unionists fighting for the United States. Forrest was blamed for the slaughter in the U.S. press, and this news may have strengthened the United States's resolve to win the war. Forrest's level of responsibility for the massacre is still debated by historians.[6]

Forrest joined the Ku Klux Klan in 1867 (two years after its founding) and was elected its first Grand Wizard.[7] The group was a loose collection of local factions throughout the former Confederacy that used violence or threats of violence to maintain white control over the newly enfranchised, formerly enslaved people. The Klan, with Forrest at the lead, suppressed the voting rights of blacks in the Southern United States through violence and intimidation during the elections of 1868. In 1869, Forrest expressed disillusionment with the lack of discipline in the white supremacist terrorist group across the South,[8] and issued a letter ordering the dissolution of the Ku Klux Klan as well as the destruction of its costumes; he then withdrew from the organization.[9] In the last years of his life, Forrest denied being a Klan member[10] and, disturbed by anti-black violence, made statements in support of racial harmony and black dignity.[11]

In June 2021, the remains of Forrest and his wife were exhumed from Health Sciences Park, where they had been buried for over 100 years, and where a monument of him once stood. They were later reburied in Columbia, Tennessee. In July 2021, Tennessee officials voted to move Forrest's bust from the State Capitol to the Tennessee State Museum.[12]

- ^ Wright, John D. (2001), The Language of the Civil War, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 210, ISBN 978-1573561358, archived from the original on May 9, 2024, retrieved April 17, 2018

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 326

- ^ A.W.R. Hawkins III; Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr.; Spencer C. Tucker (2014). "Forrest, Nathan Bedford (1821–1877)". In Tucker, Spencer C. (ed.). 500 Great Military Leaders [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-758-1. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Stephen Z. Starr (2007). The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: The War in the West, 1861–1865. LSU Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8071-3293-7. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

...Nathan Bedford Forrest, whom his superiors did not recognize for the military genius he was until it was too late...

- ^ David J Eicher (2002). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 657–. ISBN 978-0-7432-1846-7. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Gwynne, S. C. (2020). Hymns of the Republic: The Story of the Final Year of the American Civil War. Simon and Schuster. p. 332. ISBN 978-1-5011-1623-0. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

Forrest's responsibility for the massacre has been actively debated for a century and a half. Forrest spent much time after the war trying to clear his name. No direct evidence suggests that he ordered the shooting of surrendering or unarmed men, but to fully exonerate him from responsibility is also impossible.

- ^ Tabbert, Mark A. (2006). American Freemasons: Three Centuries of Building Communities. NYU Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780814783023. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ J. Michael Martinez (2012). Terrorist Attacks on American Soil From the Civil War Era to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4422-0324-2. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

Although Forrest repudiated the group's activities after less than two years, he transformed the budding terrorist organization into an effective mechanism for promoting white supremacy in the Old South.

- ^ James Michael Martinez (2007). Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7425-5078-0. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Chester L. Quarles (1999). The Ku Klux Klan and Related American Racialist and Antisemitic Organizations: A History and Analysis. McFarland. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7864-0647-0. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

memphis-appealwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Aya Elamroussi; Rebekah Riess (July 23, 2021). "Tennessee to remove bust of Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest from state Capitol". CNN. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021.