| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

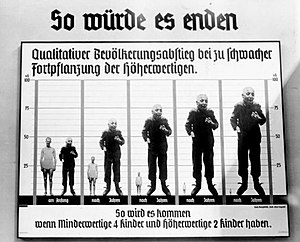

The social policies of eugenics in Nazi Germany were composed of various ideas about genetics. The racial ideology of Nazism placed the biological improvement of the German people by selective breeding of "Nordic" or "Aryan" traits at its center.[1] These policies were used to justify the involuntary sterilization and mass-murder of those deemed "undesirable".

Eugenics research in Germany before and during the Nazi period was similar to that in the United States, by which it had been heavily inspired. However, its prominence rose sharply under Adolf Hitler's leadership when wealthy Nazi supporters started heavily investing in it. The programs were subsequently shaped to complement Nazi racial policies.[2]

Those targeted for murder under Nazi eugenics policies were largely people living in private and state-operated institutions, identified as "life unworthy of life" (Lebensunwertes Leben). They included prisoners, degenerates, dissidents, and people with congenital cognitive and physical disabilities (Erbkranken) – people who were considered to be feeble-minded. In fact being diagnosed with "feeblemindedness" (German: Schwachsinn) was the main label approved in forced sterilization,[3] which included people who were diagnosed by a doctor as, or otherwise seemed to be:

- Epileptic

- Schizophrenic[4]

- Manic-depressive (now known as bipolar)

- Suffering from Cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy

- Deaf and/or blind

- Homosexual or "transvestites" (which at the time was used to refer to intersex and transgender people, particularly trans women[5][6])

- Anyone else considered to be idle, insane, and/or weak as per "feeblemindedness"

All of these were targeted for elimination from the chain of heredity. More than 400,000 people were sterilized against their will, while up to 300,000 were murdered under the Aktion T4 euthanasia program.[7][8][9][10] Thousands more also died from complications of the forced surgeries, the majority being women from forced tubal ligations.[3] In June 1935, Hitler and his cabinet made a list of seven new decrees, in which number 5 was to speed up the investigations of sterilization.[11]

An attempt to relieve the overcrowding of psychiatric hospitals, in fact, played a significant role in Germany's decision to institute compulsory sterilization and, later, the killing of psychiatric patients. [...] Hitler's letter authorizing the program to kill mental patients was dated September 1, 1939, the day German forces invaded Poland. Although the program never officially became law, Hitler guaranteed legal immunity for everyone who took part in it.[4]

In German, the concept of "eugenics" was mostly known under the term of Rassenhygiene or "racial hygiene". The loanword Eugenik was in occasional use, as was its closer loan-translation of Erbpflege. An alternative term was Volksaufartung (approximately "racial improvement").[12][13]

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

murphywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Nazi Persecution of the Mentally & Physically Disabled". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ a b Torrey, E. Fuller; Yolken, Robert H. (1 January 2010). "Psychiatric Genocide: Nazi Attempts to Eradicate Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp097. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2800142. PMID 19759092.

- ^ "2008 Houston Transgender Day of Remembrance: Transgenders and Nazi Germany". 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Illuminating the Darkness". OutSmart Magazine. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Close-up of Richard Jenne, the last child killed by the head nurse at the Kaufbeuren-Irsee euthanasia facility". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Profile in Power, Chapter VI, first section (London, 1991, rev. 2001)

- ^ Snyder, S. & D. Mitchell. Cultural Locations of Disability. University of Michigan Press. 2006.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Proctor, Robert (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674745780.

Racial Hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis.

- ^ Stefferud, A. D. (27 June 1935). "New Limitations Further limit liberty of citizens who are told what they can do: Strengthens Nazi Control". The Evening Independent Newspaper. Associated Press.

- ^ Jaeckel, Petra (2002). "Rassenhygiene in der Weimarer Zeit. Das Beispiel der »Zeitschrift für Volksaufartung« (1926–1933)". Vokus, Volkskundlich-kulturwissenschaftliche Schriften. 1 (1).

- ^ Schmitz-Berning, Cornelia (2000). Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 382.