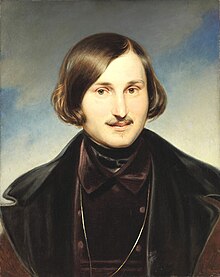

Portrait of Nikolai Gogol by Otto Friedrich Theodor von Möller (early 1840s) | |

| Born | Nikolai Vasilyevich Yanovsky 20 March 1809[a] (OS)/1 April 1809 (NS) Sorochyntsi, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 February 1852 (aged 42) Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery |

| Occupation | Playwright, short story writer, novelist |

| Language | Russian |

| Period | 1840–51 |

| Notable works |

Petersburg Tales (1833–1842)

|

| Signature | |

| |

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol[b] (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1809[a] – 4 March [O.S. 21 February] 1852) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example in his works "The Nose", "Viy", "The Overcoat", and "Nevsky Prospekt". These stories, and others such as "Diary of a Madman", have also been noted for their proto-surrealist qualities. According to Viktor Shklovsky, Gogol used the technique of defamiliarization when a writer presents common things in an unfamiliar or strange way so that the reader can gain new perspectives and see the world differently.[10] His early works, such as Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, were influenced by his Ukrainian upbringing, Ukrainian culture and folklore.[11][12] His later writing satirised political corruption in contemporary Russia (The Government Inspector, Dead Souls), although Gogol also enjoyed the patronage of Tsar Nicholas I who liked his work.[13] The novel Taras Bulba (1835), the play Marriage (1842), and the short stories "The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich", "The Portrait" and "The Carriage", are also among his best-known works.

Many writers and critics have recognized Gogol's huge influence on Russian, Ukrainian and world literature. Gogol's influence was acknowledged by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Franz Kafka, Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Nabokov, Flannery O'Connor and others.[14][15] Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé said: "We all came out from under Gogol's Overcoat."

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "Gogol". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Bojanowska, Edyta M. (2007). "Introduction". Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 9780674022911.

- ^ Lavrin, Janko (27 March 2021). "Nikolay Gogol: Ukrainian-born writer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

Ukrainian-born humorist, dramatist, and novelist whose works, written in Russian, significantly influenced the direction of Russian literature. His novel Myortvye dushi (1842; Dead Souls) and his short story "Shinel" (1842; "The Overcoat") are considered the foundations of the great 19th-century tradition of Russian realism . . . member of the petty Ukrainian gentry and a subject of the Russian Empire

- ^ Fanger, Donald (30 June 2009). The Creation of Nikolai Gogol. Harvard University Press. pp. 24, 87–88. ISBN 9780674036697. pp. 24, 87–88:

Gogol left Russian literature on the brink of that golden age of fiction which many deemed him to have originated, and to which he did, very clearly, open the way. The literary situation he entered, however, was very different, and one cannot understand the shape and sense of Gogol's career—the peripeties of his lifelong devotion to being a Russian writer, the singularity and depth of his achievement—without knowing something of that situation. ... Romantic theory exalted ethnography and folk poetry as expressions of the Volksgeist, and the Ukraine was particularly appealing to a Russian audience in this respect, being, as Gippius observes, a country both '"ours" and "not ours," neighboring, related, and yet lending itself to presentation in the light of a semi-realistic romanticism, a sort of Slavic Ausonia.' Gogol capitalized on this appeal as a mediator; by embracing his Ukrainian heritage, he became a Russian writer.

- ^ Vaag, Irina (9 April 2009). "Gogol: russe et ukrainien en même temps" [Gogol: Russian and Ukrainian at the same time]. L'Express (Interview with Vladimir Voropaev) (in French). Retrieved 2 April 2021.

Il ne faut pas diviser Gogol. Il appartient en même temps à deux cultures, russe et ukrainienne...Gogol se percevait lui-même comme russe, mêlé à la grande culture russe...En outre, à son époque, les mots "Ukraine" et "ukrainien" avaient un sens administratif et territorial, mais pas national. Le terme "ukrainien" n'était presque pas employé. Au XIXe siècle, l'empire de Russie réunissait la Russie, la Malorossia (la petite Russie) et la Biélorussie. Toute la population de ses régions se nommait et se percevait comme russe.

[We must not divide Gogol. He belongs at the same time to two cultures, Russian and Ukrainian...Gogol perceived himself as Russian, mingled with the great Russian culture...Furthermore, in his era, the words "Ukraine" and "Ukrainian" had an administrative and territorial meaning, but not national. The term "Ukrainian" was almost never used. In the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire comprised Russia, Malorossia (Little Russia) and Byelorussia. The whole population of these regions called themselves, and perceived themselves as, Russian.] - ^ Gippius, V. V. (1989). Robert A. Maguire (ed.). Gogol. Translated by Robert A. Maguire. Duke University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780822309079. p. 7:

Gogol is the one great Russian writer who has most puzzled English-speaking readers.

- ^ Joe Andrew (1995). Writers and society during the rise of Russian realism. The Macmillan Press LTD. pp. 13, 76. ISBN 9781349044214. p. 76:

He was to remain the least educated of all great Russian writers.

- ^ Amy C. Singleton (1997). Noplace Like Home: The Literary Artist and Russia's Search for Cultural Identity. SUNY Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7914-3399-7. p. 65:

In 1847 Gogol wrote that Russian literature would call forth a truly 'Russian Russia.' The clarity of this image would unite the country 'in one voice' to proclaim its long-awaited homecoming. '[Our literature] will call forth our Russia for us—our Russian Russia[...] It will elicit [Russia] from us and thus show that all of us to a man, no matter that we be of different minds, upbringing, and opinions, will say in one voice "This is our Russia; we are comfortable [priiutno] and warm here, and now we are truly at home [u sebia doma], under our native roof, and not in a foreign land."'

- ^ Postoutenko, Kirill (Summer 2000). "Gogol's eloquentia corporis: Einverleibung, Identitaet und die Grenzen der Figuration by Natasha Drubek-Meyer". The Slavic and East European Journal. 44 (2): 319–320. doi:10.2307/309969. ISSN 0037-6752. JSTOR 309969. Retrieved 5 October 2022. p. 319:

Natasha Drubek-Meyer applies this reconstructive approach (mostly in its psychological version) to a widely known yet barely explained phenomenon of Russian culture -- the retreat of the main Russian writers (Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky) from literature.

- ^ Viktor Shklovsky. String: On the dissimilarity of the similar. Moscow: Sovetsky Pisatel, 1970. – p. 230.

- ^ Ilnytzkyj, Oleh. "The Nationalism of Nikolai Gogol': Betwixt and Between?", Canadian Slavonic Papers Sep–Dec 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Karpuk, Paul A. "Gogol's Research on Ukrainian Customs for the Dikan'ka Tales". Russian Review, Vol. 56, No. 2 (April 1997), pp. 209–232.

- ^ "Очень нервный вечер. Как Николай I и Гоголь постановку «Ревизора» смотрели" (in Russian). Argumenty i Fakty. 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Natural School (Натуральная школа)". Brief Literary Encyclopedia in 9 Volumes. Moscow. 1968. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Nikolai Gogol // Concise Literary Encyclopedia in 9 volumes.