After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the sultans of the Ottoman Empire laid claim to represent the legitimate Roman emperors. This claim was based on the right of conquest and mainly rested on possession of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire for over a millennium. The sultans could also claim to be rulers of the Romans since they ruled over the former Byzantine populace, which continued to identify as such. Various titles were used by the sultans to stress their claim, including kayser-i Rûm ("Caesar of Rome") and basileus (the Byzantine ruling title).

The early sultans after the conquest of Constantinople—Mehmed II, Bayezid II, Selim I and Suleiman I—staunchly maintained that they were Roman emperors and went to great lengths to legitimize themselves as such. Constantinople was maintained as the imperial capital, Greek aristocrats (descendants of Byzantine nobility) were promoted to senior administrative positions, and architecture and culture experienced profound Byzantine influence. The claim of succession to the Roman Empire was also used to justify campaigns of conquest against Western Europe, including attempts to conquer Italy.

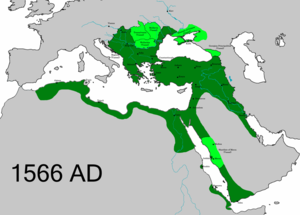

The Ottomans never formally dropped their claim to Roman imperial succession and never formally abandoned their Roman imperial titles, though the claim gradually faded and ceased to be stressed by the sultans. This development was a result of the Ottoman Empire increasingly claiming Islamic political legitimacy from the sixteenth century onwards, a result of Ottoman conquests in the Levant, Arabia, and North Africa having turned the empire from a multi-religious state to a state with a clear Muslim majority population. In turn, this necessitated a claim to legitimate political power rooted in Islamic rather than Roman tradition. Kayser-i Rûm was last used officially in the eighteenth century and sultans ceased to be referred to as basileus in Greek-language documents in the nineteenth century.

Recognition of the Ottoman claim to be Roman emperors was variable, both outside and within the Ottoman Empire. In the Islamic world, the Ottoman sultans were widely recognized as Roman emperors. The majority of the empire's Christian populace also recognized the sultans as their new emperors, though views were more variable among the cultural elite. From at least 1474 onwards, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople recognized the sultans by the title basileus. The Christian populace of the empire generally did not see the Ottoman Empire as a seamless continuation of the Byzantine Empire, but rather as an heir or successor of sorts, inheriting the former empire's legitimacy and right to universal rule. In Western Europe, the sultans were generally recognized as emperors, but not Roman emperors, an approach similar to how Western Europeans had treated the Byzantine emperors. The Ottoman claim to Roman emperorship and universal rule was challenged for centuries by the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and the Russian Empire, both of whom claimed this dignity for themselves.