Paracelsus | |

|---|---|

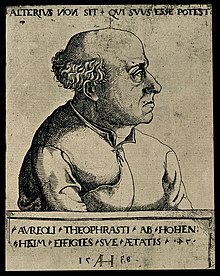

1538 portrait by Augustin Hirschvogel | |

| Born | Theophrastus von Hohenheim c. 1493[1] |

| Died | 24 September 1541 (aged 47) Salzburg, Archbishopric of Salzburg (present-day Austria) |

| Other names | Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus, Doctor Paracelsus |

| Education |

|

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Renaissance humanism |

Notable ideas | |

Preview warning: Page using Template:Infobox philosopher with unknown parameter "influences"

Preview warning: Page using Template:Infobox philosopher with unknown parameter "influenced"

| Part of a series on |

| Esotericism |

|---|

|

Paracelsus (/ˌpærəˈsɛlsəs/; German: [paʁaˈtsɛlzʊs]; c. 1493[1] – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim[11][12]), was a Swiss[13] physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.[14][15]

He was a pioneer in several aspects of the "medical revolution" of the Renaissance, emphasizing the value of observation in combination with received wisdom. He is credited as the "father of toxicology".[16] Paracelsus also had a substantial influence as a prophet or diviner, his "Prognostications" being studied by Rosicrucians in the 17th century. Paracelsianism is the early modern medical movement inspired by the study of his works.[17]

- ^ a b Pagel (1982) p. 6, citing K. Bittel, "Ist Paracelsus 1493 oder 1494 geboren?", Med. Welt 16 (1942), p. 1163, J. Strebel, Theophrastus von Hohenheim: Sämtliche Werke vol. 1 (1944), p. 38. The most frequently cited assumption that Paracelsus was born in late 1493 is due to Sudhoff, Paracelsus. Ein deutsches Lebensbild aus den Tagen der Renaissance (1936), p. 11.

- ^ Einsiedeln was under the jurisdiction of Schwyz from 1394 onward; see Einsiedeln in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Jung, C. G. (18 December 2014). The Spirit of Man in Art and Literature. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-317-53356-6.

- ^ Geoffrey Davenport, Ian McDonald, Caroline Moss-Gibbons (Editors), The Royal College of Physicians and Its Collections: An Illustrated History, Royal College of Physicians, 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Digitaal Wetenschapshistorisch Centrum (DWC) – KNAW: "Franciscus dele Boë" Archived 11 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Manchester Guardian, 19 October 1905

- ^ "The physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne". www.levity.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-226-40336-6. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ "CISSC Lecture Series: Jane Bennett, Johns Hopkins University: Impersonal Sympathy". Center for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture, Concordia University, Montreal. 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Josephson-Storm (2017), 238

- ^ Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Paracelsus, genannt Bombast von Hohenheim: ein schweizerischer Medicus, gestorben 1541, Hilscher, 1764, p. 13.

- ^ The name Philippus is only found posthumously, first on Paracelsus's tombstone. Publications during his lifetime were under the name Theophrastus ab Hohenheim or Theophrastus Paracelsus, the additional name Aureolus is recorded in 1538. Pagel (1982), 5ff.

- ^ Paracelsus self-identifies as Swiss (ich bin von Einsidlen, dess Lands ein Schweizer) in grosse Wundartznei (vol. 1, p. 56) and names Carinthia as his "second fatherland" (das ander mein Vatterland). Karl F. H. Marx, Zur Würdigung des Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1842), p. 3.

- ^ Allen G. Debus, "Paracelsus and the medical revolution of the Renaissance" Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine—A 500th Anniversary Celebration from the National Library of Medicine (1993), p. 3.

- ^ "Paracelsus", Britannica, archived from the original on 25 November 2011, retrieved 24 November 2011

- ^ "Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology". Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ De Vries, Lyke; Spruit, Leen (2017). "Paracelsus and Roman censorship – Johannes Faber's 1616 report in context". Intellectual History Review. 28 (2): 5. doi:10.1080/17496977.2017.1361060. hdl:2066/182018.