Peak oil is the point when global oil production reaches its maximum rate, after which it will begin to decline irreversibly.[2][3][4][need quotation to verify] The main concern is that global transportation relies heavily on gasoline and diesel. Transitioning to electric vehicles, biofuels, or more efficient transport (like trains and waterways) could help reduce oil demand.[5]

Peak oil relates closely to oil depletion; while petroleum reserves are finite, the key issue is the economic viability of extraction at current prices.[6][7] Initially, it was believed that oil production would decline due to reserve depletion, but a new theory suggests that reduced oil demand could lower prices, impacting extraction costs. Demand may also decline due to persistent high prices.[6][8]

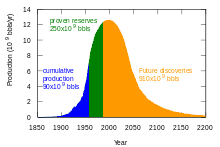

Over the last century, many predictions of peak oil timing have been made, often later proven incorrect due to increased extraction rates.[9] M. King Hubbert introduced the concept in a 1956 paper, predicting U.S. production would peak between 1965 and 1971, but his global peak oil predictions were premature because of improved drilling technology.[10] Current forecasts for the year of peak oil range from 2028 to 2050.[11] These estimates depend on future economic trends, technological advances, and efforts to mitigate climate change.[8][12][13]

- ^ "International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Peak oil theory". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Executive summary – Oil 2023 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Giles, Chris (21 December 2023). "Transatlantic resilience brings peak oil within sight". Financial Times. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Transport biofuels – Renewables 2023 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

Biofuels and renewable electricity are set to reduce transport sector oil demand by near 4 mboe/d by 2028, more than 7% of forecast transport oil demand, and when electricity from non-renewable sources such as nuclear, natural gas and coal is taken into account, this value rises to nearly 9%.

- ^ a b "Petroleum - Status of the world oil supply". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Clemente, Jude. "U.S. Oil Reserves, Resources, and Unlimited Future Supply". Forbes. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Wells, Wires, and Wheels - EROCI and the Tough Road Ahead for Oil". Investors' Corner. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Kenneth S. Deffeyes, Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage (Princeton University Press, 2001).

- ^ Hubbert, Marion King (June 1956). Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' (PDF). American Petroleum Institute. San Antonio, Texas: Shell Development Company. pp. 22–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ^ "Standard Chartered Says Peak Oil Demand Is Not Imminent". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Global oil demand may have passed peak, says BP energy report". The Guardian. 13 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Now near 100 million bpd, when will oil demand peak?". Sustainability. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.