| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

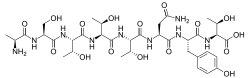

L-Alanyl-L-seryl-L-threonyl-L-threonyl-L-threonyl-L-asparaginyl-L-tyrosyl-L-threonine

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C35H55N9O16 | |

| Molar mass | 857.872 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Peptide T is an HIV entry inhibitor discovered in 1986 by Candace Pert and Michael Ruff, a US neuroscientist and immunologist.[1] Peptide T, and its modified analog Dala1-peptide T-amide (DAPTA), a drug in clinical trials, is a short peptide derived from the HIV envelope protein gp120 which blocks binding[2] and infection[3] of viral strains which use the CCR5 receptor to infect cells.

Peptide T has several positive effects related to HIV disease and Neuro-AIDS.[4] A FDG-PET neuro-imaging study in an individual with AIDS dementia who completed a 12-wk treatment with intranasal DAPTA, showed remission in 34 out of 35 brain regions after treatment.[5] A placebo-controlled, three site, 200+ patient NIH-funded clinical trial, which focused on neurocognitive improvements, was conducted between 1990 and 1995. The results showed that DAPTA was not significantly different from placebo on the study primary end points. However, 2 of 7 domains, abstract thinking and speed of information processing, did show improvement in the DAPTA group (p<.05). Furthermore, twice as many DAPTA-treated patients improved, whereas twice as many placebo patients deteriorated (P=.02). A sub-group analysis showed that DAPTA had a treatment effect and improved global cognitive performance (P=.02) in the patients who had more severe cognitive impairment.[6]

An analysis of antiviral effects from the 1996 NIH study showed peripheral viral load (combined plasma and serum) was significantly reduced in the DAPTA-treated group.[7] An eleven-person study for peptide T effects on cellular viral load showed reductions in the persistently infected monocyte reservoir to undetectable levels in most of the patients.[8] Elimination of viral reservoirs, such as the persistently infected monocytes or brain microglia, is an important treatment goal.[9]

Peptide T clinical development was stopped due to the propensity of the liquid nasal spray to lose potency upon storage and shifted to its shorter oral analog, the pentapeptide CCR2/CCR5 antagonist RAP-103 (Receptor Active Peptide) for neuropathic pain and neurodegeneration.[10] RAP-103 also blocks CCR8,[11] which may be important in neuropathic pain.[12] Inhibitors of CCR5, including DAPTA,[13][14] prevent and reverse neurodegeneration and are therapeutic targets in stroke/brain injury[15] and dementia, such as in Parkinsons Disease.[16]

- ^ Pert CB, Hill JM, Ruff MR, et al. (Dec 1986). "Octapeptides deduced from the neuropeptide receptor-like pattern of antigen T4 in brain potently inhibit human immunodeficiency virus receptor binding and T-cell infectivity". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 83 (23): 9254–8. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.9254P. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.23.9254. PMC 387114. PMID 3097649.

- ^ Polianova MT, Ruscetti FW, Pert CB, Ruff MR (Aug 2005). "Chemokine receptor-5 (CCR5) is a receptor for the HIV entry inhibitor peptide T (DAPTA)". Antiviral Res. 67 (2): 83–92. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.03.007. PMID 16002156.

- ^ Ruff MR, Melendez-Guerrero LM, Yang QE, et al. (Oct 2001). "Peptide T inhibits HIV-1 infection mediated by the chemokine receptor-5 (CCR5)". Antiviral Res. 52 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1016/S0166-3542(01)00163-2. PMID 11530189.

- ^ Ruff MR, Polianova M, Yang QE, Leoung GS, Ruscetti FW, Pert CB (Jan 2003). "Update on D-ala-peptide T-amide (DAPTA): a viral entry inhibitor that blocks CCR5 chemokine receptors". Curr. HIV Res. 1 (1): 51–67. doi:10.2174/1570162033352066. PMID 15043212. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Villemagne VL, Phillips RL, Liu X, Gilson SF, Dannals RF, Wong DF, Harris PJ, Ruff M, Pert C, Bridge P, London ED (July 1996). "Peptide T and glucose metabolism in AIDS dementia complex". J. Nucl. Med. 37 (7): 1177–80. PMID 8965193.

- ^ Heseltine PN, Goodkin K, Atkinson JH, Vitiello B, Rochon J, Heaton RK, Eaton EM, Wilkie FL, Sobel E, Brown SJ, Feaster D, Schneider L, Goldschmidts WL, Stover ES (January 1998). "Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of peptide T for HIV-associated cognitive impairment". Arch. Neurol. 55 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.55.1.41. PMID 9443710.

- ^ Goodkin K, Vitiello B, Lyman WD, et al. (Jun 2006). "Cerebrospinal and peripheral human immunodeficiency virus type 1 load in a multisite, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of D-Ala1-peptide T-amide for HIV-1-associated cognitive-motor impairment". J. Neurovirol. 12 (3): 178–89. doi:10.1080/13550280600827344. PMID 16877299. S2CID 12925475.

- ^ Polianova MT, Ruscetti FW, Pert CB, et al. (Jul 2003). "Antiviral and immunological benefits in HIV patients receiving intranasal peptide T (DAPTA)". Peptides. 24 (7): 1093–8. doi:10.1016/S0196-9781(03)00176-1. PMID 14499289. S2CID 40797488.

- ^ Crowe SM, Sonza S (Sep 2000). "HIV-1 can be recovered from a variety of cells including peripheral blood monocytes of patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a further obstacle to eradication". J. Leukoc. Biol. 68 (3): 345–50. PMID 10985250.

- ^ Padi SSV; Shi, X. Q.; Zhao, Y. Q.; Ruff, M. R.; Baichoo, N.; Pert, C. B.; Zhang, J. (2012). "Attenuation of rodent neuropathic pain by an orally active peptide, RAP-103, which potently blocks CCR2- and CCR5-mediated monocyte chemotaxis and inflammation". Pain. 153 (1): 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.022. PMID 22033364. S2CID 28310179.

- ^ Noda, M.; Tomonaga, D.; Kitazono, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Liu, J.; Rousseau, J. P.; Kinkead, R.; Ruff, M. R.; Pert, C. B. (2018). "Neuropathic pain inhibitor, RAP-103, is a potent inhibitor of microglial CCL1/CCR8". Neurochemistry International. 119: 184–189. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2017.12.005. PMID 29248693. S2CID 23454214.

- ^ Zychowska, M.; Rojewska, E.; Piotrowska, A.; Kreiner, G.; Nalepa, I.; Mika, J. (2017). "Spinal CCL1/CCR8 signaling interplay as a potential therapeutic target - Evidence from a mouse diabetic neuropathy model". International Immunopharmacology. 52: 261–271. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2017.09.021. PMID 28961489. S2CID 25901496.

- ^ Hill, J. M.; Mervis, R. F.; Avidor, R.; Moody, T. W.; Brenneman, D. E. (1993). "HIV envelope protein-induced neuronal damage and retardation of behavioral development in rat neonates". Brain Research. 603 (2): 222–233. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)91241-j. PMID 8461978. S2CID 29222082.

- ^ Socci, D. J.; Pert, C. B.; Ruff, M. R.; Arendash, G. W. (1996). "Peptide T prevents NBM lesion-induced cortical atrophy in aged rats". Peptides. 17 (5): 831–837. doi:10.1016/0196-9781(96)00106-4. PMID 8844774. S2CID 28570986.

- ^ Joy, M. T.; Ben Assayag, E.; Shabashov-Stone, D.; Liraz-Zaltsman, S.; Mazzitelli, J.; Arenas, M.; Abduljawad, N.; Kliper, E.; Korczyn, A. D.; Thareja, N. S.; Kesner, E. L.; Zhou, M.; Huang, S.; Silva, T. K.; Katz, N.; Bornstein, N. M.; Silva, A. J.; Shohami, E.; Carmichael, S. T. (2019). "CCR5 is a Therapeutic Target for Recovery after Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury". Cell. 176 (5): 1143–1157.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.044. PMC 7259116. PMID 30794775.

- ^ Mondal, S.; Rangasamy, S. B.; Roy, A.; Dasarathy, S.; Kordower, J. H.; Pahan, K. (2019). "Low-Dose Maraviroc, an Antiretroviral Drug, Attenuates the Infiltration of T Cells into the Central Nervous System and Protects the Nigrostriatum in Hemiparkinsonian Monkeys". Journal of Immunology. 202 (12): 3412–3422. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1800587. PMC 6824976. PMID 31043478.