| Inverse | perfect fourth |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Other names | diapente |

| Abbreviation | P5 |

| Size | |

| Semitones | 7 |

| Interval class | 5 |

| Just interval | 3:2 |

| Cents | |

| 12-Tone equal temperament | 700 |

| Just intonation | 701.955[1] |

In music theory, a perfect fifth is the musical interval corresponding to a pair of pitches with a frequency ratio of 3:2, or very nearly so.

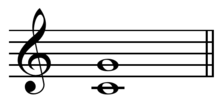

In classical music from Western culture, a fifth is the interval from the first to the last of the first five consecutive notes in a diatonic scale.[2] The perfect fifth (often abbreviated P5) spans seven semitones, while the diminished fifth spans six and the augmented fifth spans eight semitones. For example, the interval from C to G is a perfect fifth, as the note G lies seven semitones above C.

The perfect fifth may be derived from the harmonic series as the interval between the second and third harmonics. In a diatonic scale, the dominant note is a perfect fifth above the tonic note.

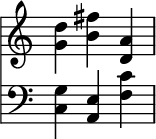

The perfect fifth is more consonant, or stable, than any other interval except the unison and the octave. It occurs above the root of all major and minor chords (triads) and their extensions. Until the late 19th century, it was often referred to by one of its Greek names, diapente.[3] Its inversion is the perfect fourth. The octave of the fifth is the twelfth.

A perfect fifth is at the start of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star"; the pitch of the first "twinkle" is the root note and the pitch of the second "twinkle" is a perfect fifth above it.

- ^

- ^ Don Michael Randel (2003), "Interval", Harvard Dictionary of Music, fourth edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press): p. 413.

- ^ William Smith; Samuel Cheetham (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities. London: John Murray. p. 550. ISBN 9780790582290.