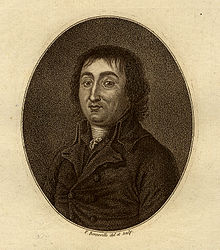

Pierre-Joseph Cambon | |

|---|---|

| |

| 27th President of the National Convention | |

| In office 19 September 1793 – 3 October 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne |

| Succeeded by | Louis-Joseph Charlier |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 June 1756 Montpellier, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 15 February 1820 (aged 63) Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| Political party | The Mountain |

Pierre-Joseph Cambon (French pronunciation: [pjɛʁ ʒozɛf kɑ̃bɔ̃], 10 June 1756 – 15 February 1820) was a French statesman. He is perhaps best known for speaking up against Maximilien Robespierre at the National Convention, sparking the end of Robespierre's reign.

Born in Montpellier, Cambon was the son of a wealthy cotton merchant. In 1785, his father retired, leaving Pierre and his two brothers to run the business, but in 1788 Pierre entered politics, and was sent by his fellow-citizens as deputy suppliant to the Estates-General, where he was mostly a spectator. In January 1790 he returned to Montpellier, was elected a member of the municipality, co-founded the Jacobin Club in that city, and on the flight to Varennes of King Louis XVI in 1791, he drew up a petition to invite the National Constituent Assembly to proclaim a Republic —the first in date of such petitions.

Elected to the Legislative Assembly, Cambon was viewed as independent, honest, and talented in the financial domain. He was the most active member of the committee of finance and was often charged to verify the state of the treasury. His analytical skills were recorded in his remarkable speech of 24 November 1791.

It was Cambon who made the initial suggestion for the state debt to be "rendered republican and uniform" and it was he who proposed to convert all the contracts of the creditors of the state into an inscription in a great book, which should be called the "Great Book of the Public Debt".[1] This proposal was implemented in 1792 when the Great Book of the Public Debt was created as a consolidation of all the states debts.[2][3]

He held his distance from political clubs and even factions, but nonetheless defended the new institutions of the state. On 9 February 1792, he succeeded in having a law passed confiscating the possessions of the émigrés, and tried to arrange the deportation of non-juring priests to French Guiana. He was the last president of the Legislative Assembly.

Re-elected to the National Convention, Cambon opposed the pretensions of the Paris Commune and the proposed grant of money to the municipality of Paris by the state. On 15 December 1792, he persuaded the convention to adopt a proclamation to all nations in favour of a universal republic. In the year after he denounced Jean-Paul Marat's placards as inciting to murder, summoned Georges Danton to give an account of his ministry, supervised the furnishing of military supplies to the French Revolutionary Army, and was a strong opponent of Charles François Dumouriez, in spite of the general's great popularity.

Cambon incurred the hatred of the theist Maximilien Robespierre (see Cult of the Supreme Being) by proposing the suppression of the pay to the clergy, which would have meant the separation of church and state. His authority grew steadily.

Although he took part in toppling Robespierre in July 1794, Cambon was targeted and pursued by the Thermidorian Reaction, and had to live in hiding in Montpellier. During the Hundred Days, he was a deputy to the lower chamber, but only took part in debates over the budget. Proscribed by the Bourbon Restoration in 1816, he died at Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, near Brussels.

- ^ Adolphe Thiers, George Thomas, Frederic Shoberl. The History of the French Revolution, Vickers, 1845 p. 329

- ^ Staff. The New Encyclopædia Britannica Encyclopædia Britannica, 1986 ISBN 0-85229-443-3, ISBN 978-0-85229-443-7. p. 758

- ^ Florin Aftalion, Martin Thom (contribution and translation), The French Revolution, Cambridge University Press, 1990, ISBN 0-521-36810-3, ISBN 978-0-521-36810-0 pp. 143,144