Pipe organ in the collegiate church of St. Michael in Neunkirchen am Brand | |

| Keyboard instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Organ, Church organ (used only for organs in houses of worship) |

| Classification | Aerophone |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | |

| Inventor(s) | Ctesibius |

| Developed | 3rd century BC |

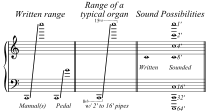

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| see Organ | |

| Builders | |

| see List of pipe organ builders and Category:Pipe organ builders | |

| Sound sample | |

|

| |

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called wind) through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ranks, each of which has a common timbre, volume, and construction throughout the keyboard compass. Most organs have many ranks of pipes of differing pitch, timbre, and volume that the player can employ singly or in combination through the use of controls called stops.

A pipe organ has one or more keyboards (called manuals) played by the hands, and a pedal clavier played by the feet; each keyboard controls its own division (group of stops). The keyboard(s), pedalboard, and stops are housed in the organ's console. The organ's continuous supply of wind allows it to sustain notes for as long as the corresponding keys are pressed, unlike the piano and harpsichord whose sound begins to dissipate immediately after a key is depressed. The smallest portable pipe organs may have only one or two dozen pipes and one manual; the largest organs may have over 33,000 pipes and as many as seven manuals.[1] A list of some of the most notable and largest pipe organs in the world can be viewed at List of pipe organs. A ranking of the largest organs in the world—based on the criterion constructed by Michał Szostak, i.e. 'the number of ranks and additional equipment managed from a single console'—can be found in the quarterly magazine The Organ[2] and in the online journal Vox Humana.[3]

The origins of the pipe organ can be traced back to the hydraulis in Ancient Greece, in the 3rd century BC,[4] in which the wind supply was created by the weight of displaced water in an airtight container. By the 6th or 7th century AD, bellows were used to supply Byzantine organs with wind.[4][5] A pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent to the West by the Byzantine emperor Constantine V as a gift to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks, in 757.[6] Pepin's son Charlemagne requested a similar organ for his chapel in Aachen in 812, beginning the pipe organ's establishment in Western European church music.[7] In England, "The first organ of which any detailed record exists was built in Winchester Cathedral in the 10th century. It was a huge machine with 400 pipes, which needed two men to play it and 70 men to blow it, and its sound could be heard throughout the city."[8] Beginning in the 12th century, the organ began to evolve into a complex instrument capable of producing different timbres. By the 17th century, most of the sounds available on the modern classical organ had been developed.[9] At that time, the pipe organ was the most complex human-made device[10]—a distinction it retained until it was displaced by the telephone exchange in the late 19th century.[11]

Pipe organs are installed in churches, synagogues, concert halls, schools, mansions, other public buildings and in private properties. They are used in the performance of classical music, sacred music, secular music, and popular music. In the early 20th century, pipe organs were installed in theaters to accompany the screening of films during the silent movie era; in municipal auditoria, where orchestral transcriptions were popular; and in the homes of the wealthy.[12] The beginning of the 21st century has seen a resurgence in installations in concert halls. A substantial organ repertoire spans over 500 years.[13]

- ^ Willey, David (2001). "The World's Largest Organs". Retrieved on 3 March 2008.

- ^ Szostak, Michał (November 2017 – January 2018). "The World's Largest Organs". The Organ. 382. The Musical Opinion Ltd: 12–28. ISSN 0030-4883. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Szostak, Michał (30 September 2018). "The Largest Pipe Organs in the World". Vox Humana. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ a b Randel "Organ", 583.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew Taste of Byzantium. IB Tauris, 2010, ISBN 9781848851658, p. 118. "the narrative of the Syrian hostage Harun Ibn Yahya...'This is what happens at Christmas...they bring what is called an organon. It is a remarkable wooden object like an oil-press, and covered with solid leather. Sixty copper pipes are placed in it, so that they project above the leather, and where they are visible above the leather they are gilded. You can only see a small part of some of them, as they are of different lengths. On one side of this structure there is a hole in which they place a bellows like a blacksmith's. three crosses are placed at the two extremities and in the middle of the organon. Two men come in to work the bellows, and the master stands and bidding to press on the pipes, and each pipe, according to its tuning and the master's playing, sounds the parsed of the Emperor. The guests are meanwhile seated at their tables, and twenty men enter with cymbals in their hands. The miscue continues while the guests continue their meal.' "

- ^ Willis, Henry. "The Organ, Its History and Development." Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. Vol. 73. No. 1. Taylor & Francis Group, 1946. p. 60

- ^ Douglas Bush and Richard Kassel eds., "The Organ, an Encyclopedia." Routledge. 2006. p. 327.

- ^ Winchester Cathedral http://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/worship-and-music/music-choir/the-cathedral-organ/ Archived 29 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Randel "Organ", 584–585.

- ^ Michael Woods, "Strange ills afflict pipe organs of Europe". Post-Gazette, 26 April 2005. Archived 22 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ N. Pippenger, "Complexity Theory", Scientific American, 239:90–100 (1978).

- ^ Smith, Rollin (1998). The Aeolian pipe organ and its music. Richmond VA USA: The Organ Historical Society. ISBN 0-913499-16-1.

- ^ Thomas, Steve, 2003. Pipe organs 101: an introduction to pipe organ basics Archived 26 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 6 May 2007.