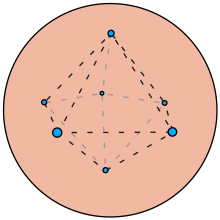

The plum pudding model was the first scientific model of the atom to describe an internal structure. It was first proposed by J. J. Thomson in 1904 following his discovery of the electron in 1897, and was rendered obsolete by Ernest Rutherford's discovery of the atomic nucleus in 1911. The model tried to account for two properties of atoms then known: that there are electrons, and that atoms have no net electric charge. Logically there had to be an equal amount of positive charge to balance out the negative charge of the electrons. As Thomson had no idea as to the source of this positive charge, he tentatively proposed that it was everywhere in the atom, and that the atom was spherical—this was the mathematically simplest hypothesis to fit the available evidence, or lack thereof. In such a sphere, the negatively charged electrons would distribute themselves in a more or less even manner throughout the volume, simultaneously repelling each other while being attracted to the positive sphere's center.[1]

Thomson attempted without success to develop a complete model that could predict other known properties of the atom, such as emission spectra and valencies. Based on experimental studies of alpha particle scattering, Ernest Rutherford developed an alternative model for the atom featuring a compact nucleus where the positive charge is concentrated.

Thomson's model is popularly referred to as the "plum pudding model" with the notion that the electrons are distributed uniformly like raisins in a plum pudding. Neither Thomson nor his colleagues ever used this analogy.[2] It seems to have been coined by popular science writers to make the model easier to understand for the layman. The analogy is perhaps misleading because Thomson likened the positive sphere to a liquid rather than a solid since he thought the electrons moved around in it.[3]

- ^ Thomson 1907, p. 103 "In default of exact knowledge of the nature of the way in which positive electricity occurs in the atom, we shall consider a case in which the positive electricity is distributed in the way most amenable to mathematical calculation, i.e., when it occurs as a sphere of uniform density, throughout which the corpuscles are distributed."

- ^ Hon, Giora; Goldstein, Bernard R. (6 September 2013). "J. J. Thomson's plum-pudding atomic model: The making of a scientific myth". Annalen der Physik. 525 (8–9): A129–A133. Bibcode:2013AnP...525A.129H. doi:10.1002/andp.201300732.

- ^ Letter from J. J. Thomson to Oliver Lodge dated 11 April 1904, quoted in Davis & Falconer 1997, p. 153:

"With regard to positive electrification I have been in the habit of using the crude analogy of a liquid with a certain amount of cohesion, enough to keep it from flying to bits under its own repulsion. I have however always tried to keep the physical conception of the positive electricity in the background because I have always had hopes (not yet realised) of being able to do without positive electrification as a separate entity and to replace it by some property of the corpuscles."