| |

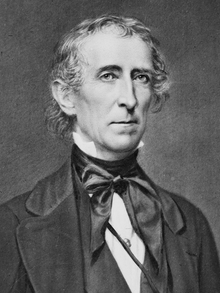

| Presidency of John Tyler April 4, 1841 – March 4, 1845 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Whig (1841) Independent (1841–1844) Democratic-Republican (1844) Independent (1844–1845) |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

The presidency of John Tyler began on April 4, 1841, when John Tyler became President of the United States upon the death of President William Henry Harrison, and ended on March 4, 1845. He had been Vice President of the United States for only 31 days when he assumed the presidency. The tenth United States president, he was the first to succeed to the office intra-term without being elected to it. To forestall constitutional uncertainty, Tyler took the presidential oath of office on April 6, assumed full presidential powers, and served out the balance of Harrison's four-year term, a precedent that would govern future extraordinary successions and eventually become codified in the Twenty-fifth Amendment. He was succeeded by James Polk of the Democratic Party.

Although nominated for the vice presidency on the Whig Party ticket in 1840, Tyler did not share the views held by some members of his party on several issues. That did not, however, become a problem until after the 1840 election, because during that campaign, the party had not taken clear stands on specific issues such as a national bank and protective tariff. Instead, it had emphasized attacking incumbent Democratic President Martin Van Buren and proclaiming colorful slogans about log cabins and hard cider. After the election, however, as a strict constructionist, Tyler found some of the program then introduced by the Whigs in Congress unconstitutional and thus vetoed several bills favored by party leader Henry Clay. Among the bills vetoed by Tyler was a measure to re-establish a national bank. In response to these vetoes, most of Tyler's cabinet resigned, and Whig congressmen expelled Tyler from the party. A resolution calling for his impeachment was introduced in the House, though it was later defeated. Despite his disagreements with Congress, Tyler did sign the Tariff of 1842, which provided needed revenue to a government still dealing with the effects of the Panic of 1837.

Tyler had more success in international affairs. His administration negotiated the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, which settled a contentious territorial dispute with the United Kingdom. Tyler also emphasized American interests in the Pacific Ocean, and he reached a commercial treaty with Qing China, known as the Treaty of Whangia. He also extended the principles of the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii, in a policy that became known as the "Tyler Doctrine." During his last two years in office Tyler pressed for the annexation of Texas, thereby introducing the annexation issue into the 1844 presidential election. Because of his injection of that issue, pro-annexation Democrats blocked the renomination of former President Van Buren, who opposed annexation and nominated instead the previously little known James K. Polk, who went on to defeat Clay, the Whig candidate, in the general election. On March 1, 1845, three days before turning the presidency over to Polk, Tyler signed a Texas annexation bill into law, and Texas would be admitted as a state in the first year of Polk's presidency.

Tyler's presidency has provoked highly divided responses, but he is generally held in low esteem by historians. Edward P. Crapol began his biography John Tyler, the Accidental President (2006) by noting: "Other biographers and historians have argued that John Tyler was a hapless and inept chief executive whose presidency was seriously flawed."[1] In The Republican Vision of John Tyler (2003), Dan Monroe observed that the Tyler presidency "is generally ranked as one of the least successful".[2] But both of those authors used those statements as a preface to their presenting a more balanced view of Tyler's presidency. Some historians and commentators have praised Tyler's foreign policy, personal conduct, and the precedent he set with regards to presidential succession.