Pseudo-Geber (or "Latin pseudo-Geber") is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (died c. 806–816, latinized as Geber),[1] an early alchemist of the Islamic Golden Age.

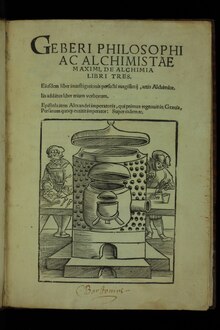

The most important work of the Latin pseudo-Geber corpus is the Summa perfectionis magisterii ("The Height of the Perfection of Mastery"), which was likely written slightly before 1310. Its actual author has been tentatively identified as Paul of Taranto.[2] The work was influential in the domain of alchemy and metallurgy in late medieval Europe. The work contains experimental demonstrations of the corpuscular nature of matter that were still being used by seventeenth-century chemists such as Daniel Sennert, who in turn influenced Robert Boyle.[3] The work is among the first to describe nitric acid, aqua regia, and aqua fortis.[4]

The existence of Jabir ibn Hayyan as a historical figure is itself in question,[5] and most of the numerous Arabic works attributed to him are, themselves, pseudepigrapha dating to c. 850–950.[6] It is common practice among historians of alchemy to refer to the earlier body of Islamic alchemy texts as the Corpus Jabirianum or Jabirian Corpus, and to the later, 13th to 14th century Latin corpus as pseudo-Geber or Latin pseudo-Geber, a term introduced by Marcellin Berthelot. The "pseudo-Geber problem" is the question of a possible relation between the two corpora. This question has long been controversially discussed. It is now mostly thought that at least parts of the Latin pseudo-Geber works are based on earlier Islamic authors such as Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925).

- ^ Delva 2017, pp. 36−37, note 6.

- ^ Newman 1985a; Newman 1985b; Newman 1991, pp. 57–103. Cf. Karpenko & Norris 2002, p. 1002; Norris 2006, p. 52, note 48; Principe 2013, pp. 55, 223 (note 10); Delva 2017, p. 38. Newman's position is rejected by Al-Hassan 2009 (also online), who argues that the work was translated from an Arabic original.

- ^ Newman 2001; Newman 2006.

- ^ Ross 1911.

- ^ Delva 2017, p. 38, 53–54.

- ^ This is the dating put forward by Kraus 1942–1943, vol. I, p. lxv. For its acceptance by other scholars, see the references in Delva 2017, p. 38, note 14. Cf. Lory 2008, also referring to Kraus 1942–1943.