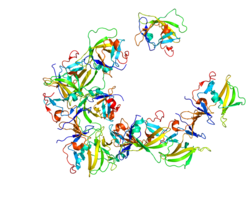

RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene I) is a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor (PRR) that can mediate induction of a type-I interferon (IFN1) response.[5] RIG-I is an essential molecule in the innate immune system for recognizing cells that have been infected with a virus. These viruses can include West Nile virus, Japanese Encephalitis virus, influenza A, Sendai virus, flavivirus, and coronaviruses.[5][6]

RIG-I is an ATP-dependent DExD/H box RNA helicase that is activated by immunostimulatory RNAs from viruses as well as RNAs of other origins. RIG-I recognizes short double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) in the cytosol with a 5' tri- or di-phosphate end or a 5' 7-methyl guanosine (m7G) cap (cap-0), but not RNA with a 5' m7G cap having a ribose 2′-O-methyl modification (cap-1).[7][8] These are often generated during a viral infection but can also be host-derived.[5][9][10][11][12] Once activated by the dsRNA, the N-terminus caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs) migrate and bind with CARDs attached to mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) to activate the signaling pathway for IFN1.[5][9]

Type-I IFNs have three main functions: to limit the virus from spreading to nearby cells, promote an innate immune response, including inflammatory responses, and help activate the adaptive immune system.[13] Other studies have shown that in different microenvironments, such as in cancerous cells, RIG-I has more functions other than viral recognition.[10] RIG-I orthologs are found in mammals, geese, ducks, some fish, and some reptiles.[9] RIG-I is in most cells, including various innate immune system cells, and is usually in an inactive state.[5][9] Knockout mice that have been designed to have a deleted or non-functioning RIG-I gene are not healthy and typically die embryonically. If they survive, the mice have serious developmental dysfunction.[9] The stimulator of interferon genes STING antagonizes RIG-I by binding its N-terminus, probably as to avoid overactivation of RIG-I signaling and the associated autoimmunity.[14]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000107201 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000040296 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d e Kell AM, Gale M (May 2015). "RIG-I in RNA virus recognition". Virology. 479–480: 110–121. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.017. PMC 4424084. PMID 25749629.

- ^ Solis M, Nakhaei P, Jalalirad M, Lacoste J, Douville R, Arguello M, et al. (February 2011). "RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling is inhibited in HIV-1 infection by a protease-mediated sequestration of RIG-I". Journal of Virology. 85 (3): 1224–1236. doi:10.1128/JVI.01635-10. PMC 3020501. PMID 21084468.

- ^ Goubau D, Schlee M, Deddouche S, Pruijssers AJ, Zillinger T, Goldeck M, et al. (October 2014). "Antiviral immunity via RIG-I-mediated recognition of RNA bearing 5'-diphosphates". Nature. 514 (7522): 372–375. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..372G. doi:10.1038/nature13590. PMC 4201573. PMID 25119032.

- ^ Devarkar SC, Wang C, Miller MT, Ramanathan A, Jiang F, Khan AG, et al. (January 2016). "Structural basis for m7G recognition and 2'-O-methyl discrimination in capped RNAs by the innate immune receptor RIG-I". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (3): 596–601. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..596D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1515152113. PMC 4725518. PMID 26733676.

- ^ a b c d e Brisse M, Ly H (2019). "Comparative Structure and Function Analysis of the RIG-I-Like Receptors: RIG-I and MDA5". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 1586. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01586. PMC 6652118. PMID 31379819.

- ^ a b Xu XX, Wan H, Nie L, Shao T, Xiang LX, Shao JZ (March 2018). "RIG-I: a multifunctional protein beyond a pattern recognition receptor". Protein & Cell. 9 (3): 246–253. doi:10.1007/s13238-017-0431-5. PMC 5829270. PMID 28593618.

- ^ Chiang JJ, Sparrer KM, van Gent M, Lässig C, Huang T, Osterrieder N, et al. (January 2018). "Viral unmasking of cellular 5S rRNA pseudogene transcripts induces RIG-I-mediated immunity". Nature Immunology. 19 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1038/s41590-017-0005-y. PMC 5815369. PMID 29180807.

- ^ Zhao Y, Ye X, Dunker W, Song Y, Karijolich J (November 2018). "RIG-I like receptor sensing of host RNAs facilitates the cell-intrinsic immune response to KSHV infection". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4841. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4841Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07314-7. PMC 6242832. PMID 30451863.

- ^ Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT (January 2014). "Regulation of type I interferon responses". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 14 (1): 36–49. doi:10.1038/nri3581. PMC 4084561. PMID 24362405.

- ^ Yu P, Miao Z, Li Y, Bansal R, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q (January 2021). "cGAS-STING effectively restricts murine norovirus infection but antagonizes the antiviral action of N-terminus of RIG-I in mouse macrophages". Gut Microbes. 13 (1): 1959839. doi:10.1080/19490976.2021.1959839. PMC 8344765. PMID 34347572.