| Rosalia | |

|---|---|

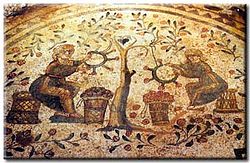

Mosaic depicting the weaving of rose wreaths.(Villa del Casale, 4th century) | |

| Observed by | Roman Empire |

| Type | Pluralistic within the context of Classical Roman religion and Imperial cult |

| Date | Varying dates mainly in May and June |

| Related to | Roman Ancestor Cult, Dionysia, Adonia, Religion in the Roman Military, Cult of the Saints, Pentecost, Green Week |

In the Roman Empire, Rosalia or Rosaria was a festival of roses celebrated on various dates, primarily in May, but scattered through mid-July. The observance is sometimes called a rosatio ("rose-adornment") or the dies rosationis, "day of rose-adornment," and could be celebrated also with violets (violatio, an adorning with violets, also dies violae or dies violationis, "day of the violet[-adornment]").[1] As a commemoration of the dead, the rosatio developed from the custom of placing flowers at burial sites. It was among the extensive private religious practices by means of which the Romans cared for their dead, reflecting the value placed on tradition (mos maiorum, "the way of the ancestors"), family lineage, and memorials ranging from simple inscriptions to grand public works. Several dates on the Roman calendar were set aside as public holidays or memorial days devoted to the dead.[2]

As a religious expression, a rosatio might also be offered to the cult statue of a deity or to other revered objects. In May, the Roman army celebrated the Rosaliae signorum, rose festivals at which they adorned the military standards with garlands. The rose festivals of private associations and clubs are documented by at least forty-one inscriptions in Latin and sixteen in Greek, where the observance is often called a rhodismos.[3]

Flowers were traditional symbols of rejuvenation, rebirth, and memory, with the red and purple of roses and violets felt to evoke the color of blood as a form of propitiation.[4] Their blooming period framed the season of spring, with roses the last of the flowers to bloom and violets the earliest.[5] As part of both festive and funerary banquets, roses adorned "a strange repast ... of life and death together, considered as two aspects of the same endless, unknown process."[6] In some areas of the Empire, the Rosalia was assimilated to floral elements of spring festivals for Dionysus, Adonis and others, but rose-adornment as a practice was not strictly tied to the cultivation of particular deities, and thus lent itself to Jewish and Christian commemoration.[7] Early Christian writers transferred the imagery of garlands and crowns of roses and violets to the cult of the saints.

- ^ C.R. Phillips, The Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by Simon Hornblower and Anthony Spawforth (Oxford University Press, 1996, 3rd edition), p. 1335; CIL 6.10264, 10239, 10248 and others. Other names include dies rosalis, dies rosae and dies rosaliorum: CIL 3.7576, 6.10234, 6.10239, 6. 10248.

- ^ Peter Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 366–367.

- ^ Christina Kokkinia, "Rosen für die Toten im griechischen Raum und eine neue Rodismos Bithynien," Museum Helveticum 56 (1999), pp. 209–210, noting that rhodismos is attested in glosses as equivalent to rosalia.

- ^ Patricia Cox Miller, The Corporeal Imagination: Signifying the Holy in Late Ancient Christianity (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), p. 74.

- ^ Christer Henriksén, A Commentary on Martial, Epigrams Book 9 (Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 59, citing Pliny, Natural History 21.64–65 and Martial, Epigram 9.11.1.

- ^ Marcu Beza, Paganism in Romanian Folklore (J.M. Dent, 1928), p. 43.

- ^ A.S. Hooey, "Rosaliae signorum," Harvard Theological Review 30.1 (1937), p. 30; Kathleen E. Corley, Marantha: Women's Funerary Rituals and Christian Origins (Fortress Press, 2010), p. 19; Kokkinia, "Rosen für die Toten," p. 208; on Jewish commemoration, Paul Trebilco, Jewish Communities in Asia Minor (Cambridge University Press, 1991, 1994 reprint), pp. 78–81.