| Sabra and Shatila massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Lebanese Civil War | |

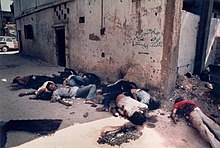

Bodies of victims of the massacre in the Sabra neighbourhood and Shatila refugee camp[1] | |

Site of the attack in Lebanon | |

| Location | Beirut, Lebanon |

| Coordinates | 33°51′46″N 35°29′54″E / 33.8628°N 35.4984°E |

| Date | 16–18 September 1982 |

| Target | Sabra neighbourhood and the Shatila refugee camp |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | 1,300 to 3,500+ |

| Victims | Palestinians and Lebanese Shias |

| Perpetrators | |

The Sabra and Shatila massacre was the 16–18 September 1982 killing of between 1,300 and 3,500 civilians—mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shias—in the city of Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. It was perpetrated by the Lebanese Forces, one of the main Christian militias in Lebanon, and supported by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) that had surrounded Beirut's Sabra neighbourhood and the adjacent Shatila refugee camp.[2]

In June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon with the intention of rooting out the PLO. By 30 August 1982, under the supervision of the Multinational Force, the PLO withdrew from Lebanon following weeks of battles in West Beirut and shortly before the massacre took place. Various forces—Israeli, Lebanese Forces and possibly also the South Lebanon Army (SLA)—were in the vicinity of Sabra and Shatila at the time of the slaughter, taking advantage of the fact that the Multinational Force had removed barracks and mines that had encircled Beirut's predominantly Muslim neighborhoods and kept the Israelis at bay during the siege of Beirut.[3] The Israeli advance over West Beirut in the wake of the PLO withdrawal, which enabled the Lebanese Forces raid, was in violation of the ceasefire agreement between the various forces.[4]

The killings are widely believed to have taken place under the command of Lebanese politician Elie Hobeika, whose family and fiancée had been murdered by Palestinian militants and left-wing Lebanese militias during the Damour massacre in 1976, itself a response to the Karantina massacre of Palestinians and Lebanese Shias at the hands of Christian militias.[5][6][7][8] In total, between 300 and 400 militiamen were involved in the massacre, including some from the South Lebanon Army.[9] As the massacre unfolded, the IDF received reports of atrocities being committed, but did not take any action to stop it.[10] Instead, Israeli troops were stationed at the exits of the area to prevent the camp's residents from leaving and, at the request of the Lebanese Forces,[11] shot flares to illuminate Sabra and Shatila through the night during the massacre.[12][13]

In February 1983, an independent commission chaired by Irish diplomat Seán MacBride, assistant to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, concluded that the IDF, as the then occupying power over Sabra and Shatila, bore responsibility for the militia's massacre.[14] The commission also stated that the massacre was a form of genocide.[15] And in February 1983, the Israeli Kahan Commission found that Israeli military personnel had failed to take serious steps to stop the killings despite being aware of the militia's actions, and deemed that the IDF was indirectly responsible for the events, and forced erstwhile Israeli defense minister Ariel Sharon to resign from his position "for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge" during the massacre.[16]

- ^ "1982, Robin Moyer, World Press Photo of the Year, World Press Photo of the Year". archive.worldpressphoto.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Fisk 2001, pp. 382–383; Quandt 1993, p. 266; Alpher 2015, p. 48; Gonzalez 2013, p. 113

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 154.

- ^ Anziska, Seth (17 September 2012). "A Preventable Massacre". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Mostyn, Trevor (25 January 2002). "Obituary: Elie Hobeika". The Guardian. guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Friedman 1982. Also articles in The New York Times on the 20, 21, and 27 September 1982.

- ^ Harris, William W. (2006). The New Face of Lebanon: History's Revenge. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-55876-392-0. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

the massacre of 1,500 Palestinians, Shi'is, and others in Karantina and Maslakh, and the revenge killings of hundreds of Christians in Damour

- ^ Hassan, Maher (24 January 2010). "Politics and war of Elie Hobeika". Egypt Independent. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Bulloch, John (1983). Final Conflict: The War in Lebanon. Century London. p. 231. ISBN 0-7126-0171-6.

- ^ Malone, Linda A. (1985). "The Kahan Report, Ariel Sharon and the Sabra Shatilla Massacres in Lebanon: Responsibility Under International Law for Massacres of Civilian Populations". Utah Law Review: 373–433. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 157: "The carnage began immediately. It was to continue without interruption till Saturday noon. Night brought no respite; the Lebanses Forces liaison officer asked for illumination and the Israelis duly obliged with flares, first from mortars and then from planes."

- ^ Friedman, Thomas (1995). From Beirut to Jerusalem. Macmillan. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-385-41372-5.

From there, small units of Lebanese Forces militiamen, roughly 150 men each, were sent into Sabra and Shatila, which the Israeli army kept illuminated through the night with flares.

- ^ Cobban, Helena (1984). The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: people, power, and politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-27216-2.

and while Israeli troops fired a stream of flares over the Palestinian refugee camps in the Sabra and Shatila districts of West Beirut, the Israeli's Christian Lebanese allies carried out a massacre of innocents there which was to shock the whole world.

- ^ MacBride et al. 1983, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Schiff & Ya'ari 1985, pp. 283–284.