| Salmonellosis | |

|---|---|

| |

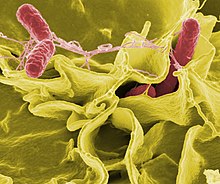

| Electron micrograph showing Salmonella typhimurium (red) invading cultured human cells | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps, vomiting[1] |

| Complications | Reactive arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome[2] |

| Usual onset | 0.5–3 days post exposure[1] |

| Duration | 4–7 days[1] |

| Types | Typhoidal, nontyphoidal[1] |

| Causes | Salmonella[1] |

| Risk factors | Old, young, weak immune system, bottle feeding, proton pump inhibitors[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Stool test, blood tests[3][1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other types of gastroenteritis[2] |

| Prevention | Proper preparation and cooking of food and supervising contact between young children and pets[4] |

| Treatment | Fluids by mouth, intravenous fluids, antibiotics[1] |

| Frequency | 1.35 million non–typhoidal cases per year (US)[1] |

| Deaths | 90,300 (2015)[5] |

Salmonellosis is a symptomatic infection caused by bacteria of the Salmonella type.[1] It is the most common disease to be known as food poisoning (though the name refers to food-borne illness in general), these are defined as diseases, usually either infectious or toxic in nature, caused by agents that enter the body through the ingestion of food. In humans, the most common symptoms are diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps, and vomiting.[1] Symptoms typically occur between 12 hours and 36 hours after exposure, and last from two to seven days.[4] Occasionally more significant disease can result in dehydration.[4] The old, young, and others with a weakened immune system are more likely to develop severe disease.[1] Specific types of Salmonella can result in typhoid fever or paratyphoid fever.[1][3] Typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever are specific types of salmonellosis, known collectively as enteric fever,[6] and are, respectively, caused by salmonella typhi and paratyphi bacteria, which are only found in humans.[7] Most commonly, salmonellosis cases arise from salmonella bacteria from animals,[8] and chicken is a major source for these infections.[9]

There are two species of Salmonella: Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica with many subspecies.[4] However, subgroups and serovars within a species may be substantially different in their ability to cause disease. This suggests that epidemiologic classification of organisms at the subspecies level may improve management of Salmonella and similar pathogens.[10][11][12]

Both vegetarian and non-vegetarian populations are susceptible to Salmonella infections due to the consumption of contaminated meat and milk.[13] Infection is usually spread by consuming contaminated meat, eggs, water or milk.[14] Other foods may spread the disease if they have come into contact with manure.[4] A number of pets including cats, dogs, and reptiles can also carry and spread the infection.[4] Diagnosis is by a stool test or blood tests.[1][3]

Efforts to prevent the disease include the proper washing, preparation, and cooking of food to appropriate temperature.[4] Mild disease typically does not require specific treatment.[4] More significant cases may require treatment of electrolyte problems and intravenous fluid replacement.[1][4] In those at high risk or in whom the disease has spread outside the intestines, antibiotics are recommended.[4]

Salmonellosis is one of the most common causes of diarrhea globally.[2] In 2015, 90,300 deaths occurred from nontyphoidal salmonellosis, and 178,000 deaths from typhoidal salmonellosis.[5] In the United States, about 1.35 million cases and 450 deaths occur from non-typhoidal salmonellosis a year.[1] In Europe, it is the second most common foodborne disease after campylobacteriosis.[2]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Salmonella". CDC. 13 November 2019. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Hald T (2013). Advances in microbial food safety: 2. Pathogen update: Salmonella. Elsevier Inc. Chapters. p. 2.2. ISBN 9780128089606. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- ^ a b c "Salmonella Infections". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Salmonella (non-typhoidal)". World Health Organization. December 2016. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ a b Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Qamar FN, Hussain W, Qureshi S (2022). "Salmonellosis Including Enteric Fever". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 69 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2021.09.007. PMID 34794677. S2CID 244281295.

- ^ "Typhoid & Paratyphoid Fever | CDC Yellow Book 2024".

- ^ "Salmonella and Food". 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Chicken and Food Poisoning". 14 November 2023.

- ^ Cohn AR, Cheng RA, Orsi RH, Wiedmann M (13 May 2021). "Moving Past Species Classifications for Risk-Based Approaches to Food Safety: Salmonella as a Case Study". Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 5: 652132. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.652132.

- ^ O'Hagan M (10 September 2021). "Salmonella: Why it's a chicken and egg thing". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-091021-1. S2CID 239248124. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Ricke SC (February 2021). "Strategies to Improve Poultry Food Safety, a Landscape Review". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 9 (1): 379–400. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-061220-023200. PMID 33156992. S2CID 226275729.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (June 2002). "Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella newport--United States, January-April 2002". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 51 (25): 545–548. PMID 12118534.

- ^ "Salmonella". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.