| Marine habitats |

|---|

|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

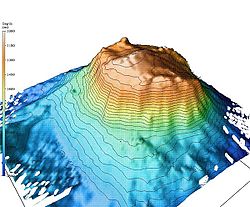

A seamount is a large submarine landform that rises from the ocean floor without reaching the water surface (sea level), and thus is not an island, islet, or cliff-rock. Seamounts are typically formed from extinct volcanoes that rise abruptly and are usually found rising from the seafloor to 1,000–4,000 m (3,300–13,100 ft) in height. They are defined by oceanographers as independent features that rise to at least 1,000 m (3,281 ft) above the seafloor, characteristically of conical form.[1] The peaks are often found hundreds to thousands of meters below the surface, and are therefore considered to be within the deep sea.[2] During their evolution over geologic time, the largest seamounts may reach the sea surface where wave action erodes the summit to form a flat surface. After they have subsided and sunk below the sea surface, such flat-top seamounts are called "guyots" or "tablemounts".[1]

Earth's oceans contain more than 14,500 identified seamounts,[3] of which 9,951 seamounts and 283 guyots, covering a total area of 8,796,150 km2 (3,396,210 sq mi), have been mapped[4] but only a few have been studied in detail by scientists. Seamounts and guyots are most abundant in the North Pacific Ocean, and follow a distinctive evolutionary pattern of eruption, build-up, subsidence and erosion. In recent years, several active seamounts have been observed, for example Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Lōʻihi) in the Hawaiian Islands.

Because of their abundance, seamounts are one of the most common marine ecosystems in the world. Interactions between seamounts and underwater currents, as well as their elevated position in the water, attract plankton, corals, fish, and marine mammals alike. Their aggregational effect has been noted by the commercial fishing industry, and many seamounts support extensive fisheries. There are ongoing concerns on the negative impact of fishing on seamount ecosystems, and well-documented cases of stock decline, for example with the orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus). 95% of ecological damage is done by bottom trawling, which scrapes whole ecosystems off seamounts.

Because of their large numbers, many seamounts remain to be properly studied, and even mapped. Bathymetry and satellite altimetry are two technologies working to close the gap. There have been instances where naval vessels have collided with uncharted seamounts; for example, Muirfield Seamount is named after the ship that struck it in 1973. However, the greatest danger from seamounts are flank collapses; as they get older, extrusions seeping in the seamounts put pressure on their sides, causing landslides that have the potential to generate massive tsunamis.

- ^ a b IHO, 2008. Standardization of Undersea Feature Names: Guidelines Proposal form Terminology, 4th ed. International Hydrographic Organization and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Monaco.

- ^ Nybakken, James W. and Bertness, Mark D., 2008. Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach. Sixth Edition. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco

- ^ Watts, T. (August 2019). "Science, Seamounts and Society". Geoscientist: 10–16.

- ^ Harris, P. T.; MacMillan-Lawler, M.; Rupp, J.; Baker, E. K. (2014). "Geomorphology of the oceans". Marine Geology. 352: 4–24. Bibcode:2014MGeol.352....4H. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.01.011.