The Tunnel entrance on the English side. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

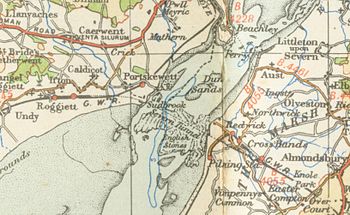

| Location | River Severn |

| Coordinates | 51°34′30″N 2°41′20″W / 51.575°N 2.6889°W |

| Start | South Gloucestershire |

| End | Monmouthshire |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 1873 |

| Opened | 1886 |

| Traffic | Railway |

| Technical | |

| Design engineer | Sir John Hawkshaw |

| Length | 7,008 m (4.355 mi) |

The Severn Tunnel (Welsh: Twnnel Hafren) is a railway tunnel in the United Kingdom, linking South Gloucestershire in the west of England to Monmouthshire in south Wales under the estuary of the River Severn. It was constructed by the Great Western Railway (GWR) between 1873 and 1886 for the purpose of dramatically shortening the journey times of their trains, passenger and goods alike, between South Wales and Western England. It has often been regarded as the crowning achievement of GWR's chief engineer Sir John Hawkshaw.[1]

Prior to the tunnel's construction, lengthy detours were necessary for all traffic between South Wales and Western England, which either used ship or a lengthy diversion upriver via Gloucester. Recognising the value of such a tunnel, the GWR sought its development, tasking Hawkshaw with its design and later contracting the civil engineer Thomas A. Walker to undertake its construction, which commenced in March 1873. Work proceeded smoothly until October 1879, at which point significant flooding of the tunnel occurred from what is now known as “The Great Spring”. Through strenuous and innovative efforts, the flooding was contained and work was able to continue, albeit with a great emphasis on drainage. Structurally completed during 1885, the first passenger train was run through the tunnel on 1 December 1886, nearly 14 years after the commencement of work.

Following its opening, the tunnel quickly formed a key element of the main trunk railway line between southern England and South Wales. Amongst other services, the GWR operated a car shuttle train service through the tunnel for many decades. However, the tunnel has also presented especially difficult conditions, both operationally and in terms of infrastructure and structural maintenance. On average, around 50 million litres of water per day infiltrates the tunnel, necessitating the permanent operation of several large pumping engines. Originally, during much of the steam era, a large number of pilot and banking locomotives were required to assist heavy trains traverse the challenging gradients of the tunnel, which were deployed from nearby marshalling yards.

The tunnel is 7,008 m (4.355 mi) long, although only 3,621 m (2.250 mi) of its length are under the river. It was the longest underwater tunnel in the world until 1987 — when Japan’s Seikan Tunnel linking the islands of Honshu and Hokkaido took the title — and, for more than 100 years, it was the longest mainline railway tunnel within the UK. It was finally exceeded in this capacity during 2007 with the opening of the two major tunnels of High Speed 1, forming a part of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link. In 2016, overhead line equipment (OHLE) was installed in the tunnel to allow the passage of electric traction; this work was undertaken as one element of the wider 21st-century modernisation of the Great Western main line.

- ^ Beaumont, Martin (2015). Sir John Hawkshaw 1811–1891. The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Society www.lyrs.org.uk. pp. 116–125. ISBN 978-0-9559467-7-6.