| Spirochaetes | |

|---|---|

| |

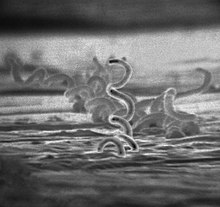

| Treponema pallidum, a spirochaete which causes syphilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Spirochaetota Garrity and Holt 2021[3] |

| Class: | Spirochaetia Paster 2020[1]: 471–563 [2] |

| Orders | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Fig. 2: A side-view of a spirochete cell which shows two axial filaments in opposing motion. One axial filament rotates in a clockwise orientation; an adjacent axial filament rotates in a counter-clockwise orientation. Rotation of the endoflagella creates torsion and drives the corkscrew rotation of the cell.

Fig. 3: An expanded view of the cellular membranes that surround endoflagellum. Both the inner and outer membrane contain a phospholipid bi-layer, with non-polar fatty acid chains in-ward of polar phosphorus heads. Peptidoglycan, the cell wall, provides structure in bacterial microorganisms. Axial filaments are superior to the peptidoglycan.

A spirochaete (/ˈspaɪroʊˌkiːt/)[4] or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (also called Spirochaetes[5] /ˌspaɪroʊˈkiːtiːz/), which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) Gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or spiraled, hence the name) cells.[6] Spirochaetes are chemoheterotrophic in nature, with lengths between 3 and 500 μm and diameters around 0.09 to at least 3 μm.[7]

Spirochaetes are distinguished from other bacterial phyla by the location of their flagella, called endoflagella, or periplasmic flagella, which are sometimes called axial filaments.[8][9] Endoflagella are anchored at each end (pole) of the bacterium within the periplasmic space (between the inner and outer membranes) where they project backwards to extend the length of the cell.[10] These cause a twisting motion which allows the spirochaete to move. When reproducing, a spirochaete will undergo asexual transverse binary fission. Most spirochaetes are free-living and anaerobic, but there are numerous exceptions. Spirochaete bacteria are diverse in their pathogenic capacity and the ecological niches that they inhabit, as well as molecular characteristics including guanine-cytosine content and genome size.[11][12]

- ^ Paster BJ (2010). "Class I. Spirochaetia class. nov.". In Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 4—The Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes (Mollicutes), Acidobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Dictyoglomi, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-68572-4. ISBN 978-0-387-95042-6.

- ^ Oren A, Garrity GM (2020). "Validation list no. 195. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 70 (9): 4844–4847. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004366. PMID 32993851. S2CID 222147003.

- ^ Oren A, Garrity GM (2021). "Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 71 (10): 5056. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.005056. PMID 34694987. S2CID 239887308.

- ^ "SPIROCHAETE | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021.

- ^ Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Elsevier.

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ Margulis L, Ashen JB, Solé M, Guerrero R (August 1993). "Composite, large spirochetes from microbial mats: spirochete structure review". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (15): 6966–6970. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.6966M. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.15.6966. PMC 47056. PMID 8346204.

- ^ Nakamura S (April 2020). "Spirochete Flagella and Motility". Biomolecules. 10 (4): 550. doi:10.3390/biom10040550. PMC 7225975. PMID 32260454.

- ^ Carroll KC, Hobden JA, Miller S (2019). "Spirochetes and Other Spiral Microorganisms". Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology. McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Madigan MT (2019). Brock biology of microorganisms (Fifteenth, Global ed.). NY, NY: Pearson. p. 519. ISBN 9781292235103.

- ^ Paster BJ (2011). "Phylum XV. Spirochaetes Garrity and Holt.". In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Garrity GM, Staley JT (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer. p. 471.

- ^ Paster BJ (2011). "Family I. Sprochaetes Swellengrebel 1907, 581AL.". In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Garrity GM, Staley JT (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer. pp. 473–531.