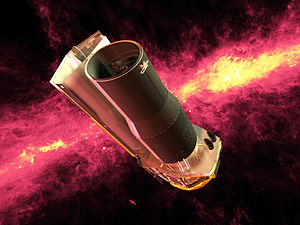

An artist rendering of the Spitzer Space Telescope | |||||||||

| Names | Space Infrared Telescope Facility | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Infrared space telescope | ||||||||

| Operator | NASA / JPL / Caltech | ||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2003-038A | ||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 27871 | ||||||||

| Website | www.spitzer.caltech.edu | ||||||||

| Mission duration | Planned: 2.5 to 5+ years[1] Primary mission: 5 years, 8 months, 19 days Final: 16 years, 5 months, 4 days | ||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Ball Aerospace | ||||||||

| Launch mass | 950 kg (2,094 lb)[1] | ||||||||

| Dry mass | 884 kg (1,949 lb) | ||||||||

| Payload mass | 851.5 kg (1,877 lb)[1] | ||||||||

| Power | 427 W[2] | ||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||

| Launch date | 25 August 2003, 05:35:39 UTC[3] | ||||||||

| Rocket | Delta II 7920H[4] | ||||||||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17B | ||||||||

| Entered service | 18 December 2003 | ||||||||

| End of mission | |||||||||

| Disposal | Deactivated in Earth-trailing orbit | ||||||||

| Deactivated | 30 January 2020[5] | ||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||

| Reference system | Heliocentric[1] | ||||||||

| Regime | Earth-trailing[1] | ||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.011[6] | ||||||||

| Perihelion altitude | 1.003 AU[6] | ||||||||

| Aphelion altitude | 1.026 AU[6] | ||||||||

| Inclination | 1.13°[6] | ||||||||

| Period | 373.2 days[6] | ||||||||

| Epoch | 16 March 2017 00:00:00 | ||||||||

| Main telescope | |||||||||

| Type | Ritchey–Chrétien[7] | ||||||||

| Diameter | 0.85 m (2.8 ft)[1] | ||||||||

| Focal length | 10.2 m (33 ft) | ||||||||

| Wavelengths | infrared, 3.6–160 μm[8] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

The Spitzer Space Telescope, formerly the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF), was an infrared space telescope launched in 2003, that was deactivated when operations ended on 30 January 2020.[5][9] Spitzer was the third space telescope dedicated to infrared astronomy, following IRAS (1983) and ISO (1995–1998). It was the first spacecraft to use an Earth-trailing orbit, later used by the Kepler planet-finder.

The planned mission period was to be 2.5 years with a pre-launch expectation that the mission could extend to five or slightly more years until the onboard liquid helium supply was exhausted. This occurred on 15 May 2009.[10] Without liquid helium to cool the telescope to the very low temperatures needed to operate, most of the instruments were no longer usable. However, the two shortest-wavelength modules of the IRAC camera continued to operate with the same sensitivity as before the helium was exhausted, and continued to be used into early 2020 in the Spitzer Warm Mission.[11][12]

During the warm mission, the two short wavelength channels of IRAC operated at 28.7 K and were predicted to experience little to no degradation at this temperature compared to the nominal mission. The Spitzer data, from both the primary and warm phases, are archived at the Infrared Science Archive (IRSA).

In keeping with NASA tradition, the telescope was renamed after its successful demonstration of operation, on 18 December 2003. Unlike most telescopes that are named by a board of scientists, typically after famous deceased astronomers, the new name for SIRTF was obtained from a contest open to the general public. The contest led to the telescope being named in honor of astronomer Lyman Spitzer, who had promoted the concept of space telescopes in the 1940s.[13] Spitzer wrote a 1946 report for RAND Corporation describing the advantages of an extraterrestrial observatory and how it could be realized with available or upcoming technology.[14][15] He has been cited for his pioneering contributions to rocketry and astronomy, as well as "his vision and leadership in articulating the advantages and benefits to be realized from the Space Telescope Program."[13]

The US$776 million[16] Spitzer was launched on 25 August 2003 at 05:35:39 UTC from Cape Canaveral SLC-17B aboard a Delta II 7920H rocket.[3] It was placed into a heliocentric (as opposed to a geocentric) orbit trailing and drifting away from Earth's orbit at approximately 0.1 astronomical units per year (an "Earth-trailing" orbit[1]).

The primary mirror is 85 centimeters (33 in) in diameter, f/12, made of beryllium and was cooled to 5.5 K (−268 °C; −450 °F). The satellite contains three instruments that allowed it to perform astronomical imaging and photometry from 3.6 to 160 micrometers, spectroscopy from 5.2 to 38 micrometers, and spectrophotometry from 55 to 95 micrometers.[8]

- ^ a b c d e f g "About Spitzer: Fast Facts". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2008. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- ^ "The Solar Panel Assembly". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b Harwood, William (25 August 2003). "300th Delta rocket launches new window on Universe". Spaceflight Now for CBS News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "Spitzer Space Telescope: Launch/Orbital Information". National Space Science Data Center. 2003-038A. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

SciAm 2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e "HORIZONS Web-Interface". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "About Spitzer: Spitzer's Telescope". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- ^ a b Van Dyk, Schuyler; Werner, Michael; Silbermann, Nancy (March 2013) [2010]. "3.2: Observatory Description". Spitzer Telescope Handbook. Infrared Science Archive. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Mann, Adam (30 January 2020). "NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope Ends 16-Year Mission of Discovery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (15 May 2009). "NASA's Spitzer Begins Warm Mission" (Press release). Pasadena, California: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. ssc2009-12, jpl2009-086. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Stauffer, John R.; Mannings, Vincent; Levine, Deborah; Chary, Ranga Ram; Wilson, Gillian; Lacy, Mark; Grillmair, Carl; Carey, Sean; Stolovy, Susan (August 2007). The Spitzer Warm Mission Science Prospects (PDF). Spitzer Warm Mission Workshop. AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 943. American Institute of Physics. pp. 43–66. Bibcode:2007AIPC..943...43S. doi:10.1063/1.2806787. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Cycle-6 Warm Mission". Spitzer Science Center. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ a b Applewhite, Denise (11 March 2004). "Lyman Spitzer Jr". Jet Propulsion Laboratory & Princeton University. Archived from the original on 21 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Carolyn Collins Petersen; John C. Brandt (1998). Hubble vision: further adventures with the Hubble Space Telescope. CUP Archive. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-521-59291-8.

- ^ Zimmerman, Robert (2008). The universe in a mirror: the saga of the Hubble Telescope and the visionaries who built it. Princeton University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-691-13297-6.

- ^ "Spitzer Space Telescope Fast Facts". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2020.