| Spring and Autumn Annals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

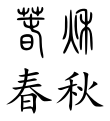

Chunqiu in seal script (top) and regular script (bottom) characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | springs and autumns | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Kinh Xuân Thu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 經春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 춘추 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | しゅんじゅう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Spring and Autumn Annals is an ancient Chinese chronicle that has been one of the core Chinese classics since ancient times. The Annals is the official chronicle of the State of Lu, and covers a 242-year period from 722 to 481 BCE. It is the earliest surviving Chinese historical text to be arranged in annals form.[1] Because it was traditionally regarded as having been compiled by Confucius—after a claim to this effect by Mencius—it was included as one of the Five Classics of Chinese literature.

The Annals records main events that occurred in Lu during each year, such as the accessions, marriages, deaths, and funerals of rulers, battles fought, sacrificial rituals observed, celestial phenomena considered ritually important, and natural disasters.[1] The entries are tersely written, averaging only 10 characters per entry, and contain no elaboration on events or recording of speeches.[1]

During the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), a number of commentaries to the Annals were created that attempted to elaborate on or find deeper meaning in the brief entries in the Annals. The Zuo Zhuan, the best known of these commentaries, became a classic in its own right, and is the source of more Chinese sayings and idioms than any other classical work.[1]

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson (2012), p. 612.