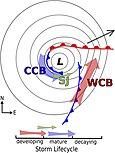

A sting jet is a narrow, transient and mesoscale airstream that descends from the mid-troposphere to the surface in some extratropical cyclones.[1] When present, sting jets produce some of the strongest surface-level winds in extratropical cyclones and can generate damaging wind gusts in excess of 50 m/s (180 km/h; 110 mph).[2][3][4] Sting jets are short-lived, lasting on the order of hours,[5] and the area subjected to their strong winds is typically no wider than 100 km (62 mi), making their effects highly localised. Studies have identified sting jets in mid-latitude cyclones primarily in the northern Atlantic and western Europe, though they may occur elsewhere. The storms that produce sting jets have tended to follow the Shapiro–Keyser model of extratropical cyclone development. Among these storms, sting jets tend to form following storm's highest rate of intensification.

Sting jets were first formally identified in 2004 by Keith Browning at the University of Reading in an analysis of the great storm of 1987, though forecasters have known of its effects since at least the late 1960s.[6] The sting jet emerges from within the end of an extratropical cyclone's cloud head – a hook-shaped region of cloudiness near the centre of low pressure – and accelerates as it descends to the surface. Multiple mechanisms explaining why sting jets form and why they accelerate during descent; frontolysis, the release of conditional symmetric instability, and evaporative cooling are often cited as influences on sting jet evolution. The presence of these factors can be used to forecast the jets themselves as sting jets are too small to be resolved by most globally-spanning weather models. The speed of the winds brought to the surface by a sting jet is dependent on the stability of the atmosphere within the layer of air near the surface. Sting jets can produce multiple areas of damaging winds, and a single cyclone can produce multiple sting jets.

- ^ Schultz & Browning 2017, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Schultz & Browning 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Baker 2009, p. 143.

- ^ Gliksman et al. 2023, p. 2174.

- ^ Clark & Gray 2018, p. 967.

- ^ Martínez-Alvarado, Weidle & Gray 2010, p. 4055.