Wayside crosses and Celtic inscribed stones are found in Cornwall in large numbers; the inscribed stones (about 40 in number) are thought to be earlier in date than the crosses and are a product of Celtic Christian society. It is likely that the crosses represent a development from the inscribed stones but nothing is certain about the dating of them. In the late Middle Ages it is likely that their erection was very common and they occur in locations of various types, e.g. by the wayside, in churchyards, and in moorlands. Those by roadsides and on moorlands were doubtless intended as route markings. A few may have served as boundary stones, and others like the wayside shrines found in Catholic European countries. Crosses to which inscriptions have been added must have been memorial stones. According to W. G. V. Balchin "The crosses are either plain or ornamented, invariably carved in granite, and the great majority are of the wheel-headed Celtic type." Their distribution shows a greater concentration in west Cornwall and a gradual diminution further east and further north. In the extreme northeast none are found because it had been settled by West Saxons. The cross in Perran Sands has been dated by Charles Henderson as before 960 AD; that in Morrab Gardens, Penzance, has been dated by R. A. S. Macalister as before 924 AD; and the Doniert Stone is thought to be a memorial to King Dumgarth (died 878).[1]

Celtic art is found in Cornwall, often in the form of stone crosses of various types. Cornwall boasts the highest density of traditional 'Celtic crosses' of any nation (some 400). Charles Henderson reported in 1930 that there were 390 ancient crosses and in the next forty years a number of others have come to light.[2] In the 1890s Arthur G. Langdon collected as much information as he could about these crosses (Old Cornish Crosses; Joseph Pollard, Truro, 1896) and one hundred years later Andrew G. Langdon has done a survey in the form of five volumes of Stone Crosses in Cornwall, each volume covering a region (e.g. Mid Cornwall) which the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies has published.[3]

Similar crosses are also found on Dartmoor in Devon.

In modern times many crosses were erected as war memorials and to celebrate events such as the millennium. "Here is an example of continuity in cultural traits extending over many generations: for we can look beyond the medieval cross to the inscribed stone and even farther back to the prehistoric mênhir, and yet bring the custom right up-to-date with the twentieth-century war memorial."—W. G. V. Balchin (1954).[4]

"The Celtic crosses found in their hundreds at the roadside, in churchyards, towns and in the open landscape ... are the most pervasive and memorable evidence of the presence of Christianity across medieval Cornwall. They were long considered to be pre-Conquest but it is now believed that they began to be erected in the 9th century with the majority dating between then and the 13th century, though documentary evidence suggests that some were still being put up as late as the mid 15th century. Two of the best pre-Conquest examples are St Piran's Cross near St Piran's Oratory, mentioned in a charter of 960, and King Doniert's Stone (a cross shaft) near St Cleer commemorating Doniert's death in 875. Most crosses are of granite and they are especially numerous ... in the Cardinham area and ... around Sancreed, with smaller clusters in Wendron and Lanivet. The most distinctive is the Celtic wheel-head design, which has many variants, but there are significant numbers of holed crosses that are pierced right through, and numerous Latin crosses. The most elaborate are the larger and more decorated churchyard crosses ... Their purpose is varied: the most common is the wayside cross to mark directions, and there are also a large number of boundary crosses... Some are memorial crosses and a few are true village or market crosses, though some of the latter have been adapted from wayside crosses. In situ crosses are rare, with many rediscovered, relocated and re-erected since the later 19th century, and more still coming to light today."--Peter Beacham.[5]

-

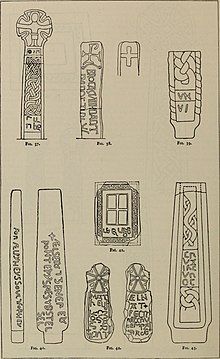

Fig. 3: some more stone crosses

-

Fig. 4: some more stone crosses

-

Fig. 5: some more stone crosses

-

Fig, 6: some more stone crosses

- ^ Balchin (1954), pp. 62–63

- ^ Hardy, Evelyn (1972, April/May) "Hardy's runic stone?", in: London Magazine; New series, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 85–91; citing Henderson's Cornwall: a Survey (1930), made for the Council for the Protection of Rural England

- ^ 1: North Cornwall; 2: Mid Cornwall; 3: East Cornwall; 4: West Penwith; 5: West Cornwall. There are 2nd eds. of nos. 1, 2 and 3. N.B. The two Langdons are unrelated.

- ^ Balchin, W. G. V. (1954) Cornwall: an illustrated essay on the history of the landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton; p. 63

- ^ Beacham, Peter & Pevsner, Nikolaus (2014) Cornwall. (The Buildings of England.) New Haven: Yale University Press; p. 23