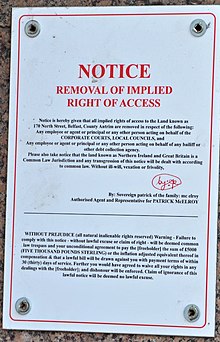

The strawman theory (also called the strawman illusion) is a pseudolegal conspiracy theory originating in the redemption/A4V movement and prevalent in antigovernment and tax protester movements such as sovereign citizens and freemen on the land. The theory holds that an individual has two personas, one of flesh and blood and the other a separate legal personality (i.e., the "strawman") and that one's legal responsibilities belong to the strawman rather than the physical individual.[1]

Pseudolaw advocates claim that it is possible, through the use of certain "redemption" procedures and documents, to separate oneself from the "strawman", therefore becoming free of the rule of law.[2][3] Hence, the main use of strawman theory is in escaping and denying liabilities and legal responsibility. Tax protesters, "commercial redemption" and "get out of debt free" scams claim that one's debts and taxes are the responsibility of the strawman and not of the real person. They back this claim by misreading the legal definition of person[4] and misunderstanding the distinction between a juridical person[5] and a natural person.[6]

Canadian legal scholar Donald J. Netolitzky has called the strawman theory "the most innovative component of the Pseudolaw Memeplex".[2]

Courts have uniformly rejected arguments relying on the strawman theory,[7][8] which is recognized in law as a scam; the FBI considers anyone promoting it a likely fraudster,[9] and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) considers it a frivolous argument and fines people who claim it on their tax returns.[10][11]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

SPLC1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Netolitzky, Donald (2018). "A Rebellion of Furious Paper: Pseudolaw As a Revolutionary Legal System". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3177484. ISSN 1556-5068. SSRN 3177484.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

peculiarwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Blacks_Personwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Blacks_Jpersonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Blacks_Npersonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Netolitzky, Donald J. (2018). "Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments as Magic and Ceremony". Alberta Law Review: 1045. doi:10.29173/alr2485. ISSN 1925-8356. S2CID 158051933. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ John D. Rooke (2012-09-18). "Reasons for Decision of the Associate Chief Justice J. D. Rooke". canlii.org. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

FBIwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

IRSwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Liiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).