| Subacromial bursitis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Shoulder joint | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

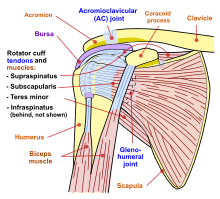

Subacromial bursitis is a condition caused by inflammation of the bursa that separates the superior surface of the supraspinatus tendon (one of the four tendons of the rotator cuff) from the overlying coraco-acromial ligament, acromion, and coracoid (the acromial arch) and from the deep surface of the deltoid muscle.[1] The subacromial bursa helps the motion of the supraspinatus tendon of the rotator cuff in activities such as overhead work.

Musculoskeletal complaints are one of the most common reasons for primary care office visits, and rotator cuff disorders are the most common source of shoulder pain.[2]

Primary inflammation of the subacromial bursa is relatively rare and may arise from autoimmune inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, crystal deposition disorders such as gout or pseudogout, calcific loose bodies, and infection.[1] More commonly, subacromial bursitis arises as a result of complex factors, thought to cause shoulder impingement symptoms. These factors are broadly classified as intrinsic (intratendinous) or extrinsic (extratendinous). They are further divided into primary or secondary causes of impingement. Secondary causes are thought to be part of another process such as shoulder instability or nerve injury.[3]

In 1983 Neer described three stages of impingement syndrome.[4] He noted that "the symptoms and physical signs in all three stages of impingement are almost identical, including the 'impingement sign'..., arc of pain, crepitus, and varying weakness". The Neer classification did not distinguish between partial-thickness and full-thickness rotator cuff tears in stage III.[4] This has led to some controversy about the ability of physical examination tests to accurately diagnose between bursitis, impingement, impingement with or without rotator cuff tear and impingement with partial versus complete tears.

In 2005, Park et al. published their findings which concluded that a combination of clinical tests were more useful than a single physical examination test. For the diagnosis of impingement disease, the best combination of tests were "any degree (of) a positive Hawkins–Kennedy test, a positive painful arc sign, and weakness in external rotation with the arm at the side", to diagnose a full thickness rotator cuff tear, the best combination of tests, when all three are positive, were the painful arc, the drop-arm sign, and weakness in external rotation.[5]

- ^ a b Salzman KL, Lillegard WA, Butcher JD (1997). "Upper extremity bursitis". Am Fam Physician. 56 (7): 1797–806, 1811–2. PMID 9371010.

- ^ Arcuni SE (2000). "Rotator cuff pathology and subacromial impingement". Nurse Pract. 25 (5): 58, 61, 65–6 passim. doi:10.1097/00006205-200025050-00005. PMID 10826138.

- ^ Bigliani LU, Levine WN (1997). "Subacromial impingement syndrome". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 79 (12): 1854–68. doi:10.2106/00004623-199712000-00012. PMID 9409800.

- ^ a b Neer CS (1983). "Impingement lesions". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. (173): 70–7. PMID 6825348.

- ^ Park HB, Yokota A, Gill HS, El Rassi G, McFarland EG (2005). "Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 87 (7): 1446–55. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02335. PMID 15995110.