In philosophy, supervenience refers to a relation between sets of properties or sets of facts. X is said to supervene on Y if and only if some difference in Y is necessary for any difference in X to be possible.

Examples of supervenience, in which case the truth values of some propositions cannot vary unless the truth values of some other propositions vary, include:

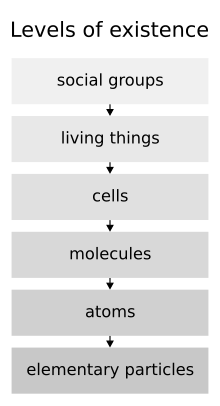

- Whether there is a table in the living room supervenes on the positions of molecules in the living room.

- The truth value of (A) supervenes on the truth value of its negation, (¬A), and vice versa.

- Properties of individual molecules supervene on the properties of individual atoms.

- One's moral character supervenes on one's action(s).

Supervenience is of interest to philosophers because it differs from other nearby relations, for example entailment. Some philosophers believe it possible for some A to supervene on some B without being entailed by B. In such cases it may seem puzzling why A should supervene on B and equivalently why changes in A should require changes in B. Two important applications of supervenience involve cases like this. One of these is the supervenience of mental properties (like the sensation of pain) on physical properties (like the firing of 'pain neurons'). A second is the supervenience of normative facts (facts about how things ought to be) on natural facts (facts about how things are).

It is sometimes claimed[by whom?] that what is at issue in these problems is the supervenience claim itself. For example, it has been claimed that what is at issue with respect to the mind-body problem is whether mental phenomena do in fact supervene on physical phenomena. This is incorrect. It is by and large agreed that some form of supervenience holds in these cases: Pain happens when the appropriate neurons fire. The disagreement is over why this is so. Materialists claim that we observe supervenience because the neural phenomena entail the mental phenomena, while dualists deny this. The dualist's challenge is to explain supervenience without entailment.[citation needed]

The problem is similar with respect to the supervenience of normative facts on natural facts. Discussing the is-ought problem it is agreed that facts about how persons ought to act are not entailed by natural facts but cannot vary unless natural facts vary, and this rigid binding without entailment might seem puzzling.

The possibility of "supervenience without entailment" or "supervenience without reduction" is contested territory among philosophers.