| Thylacine Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A female thylacine and her juvenile offspring in the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., c. 1903[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Dasyuromorphia |

| Family: | †Thylacinidae |

| Genus: | †Thylacinus |

| Species: | †T. cynocephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Thylacinus cynocephalus | |

| |

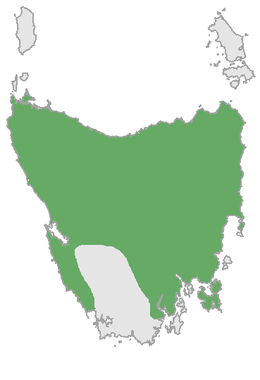

| Historic thylacine range in Tasmania (in green)[4] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List | |

The thylacine (/ˈθaɪləsiːn/; binomial name Thylacinus cynocephalus), also commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, is an extinct carnivorous marsupial that was native to the Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea. The thylacine died out in New Guinea and mainland Australia around 3,600–3,200 years ago, prior to the arrival of Europeans, possibly because of the introduction of the dingo, whose earliest record dates to around the same time, but which never reached Tasmania. Prior to European settlement, around 5,000 remained in the wild on Tasmania. Beginning in the nineteenth century, they were perceived as a threat to the livestock of farmers and bounty hunting was introduced. The last known of its species died in 1936 at Hobart Zoo in Tasmania. The thylacine is widespread in popular culture and is a cultural icon in Australia.

The thylacine was known as the Tasmanian tiger because of the dark transverse stripes that radiated from the top of its back, and it was called the Tasmanian wolf because it resembled a medium- to large-sized canid. The name thylacine is derived from thýlakos meaning "pouch" and ine meaning "pertaining to", and refers to the marsupial pouch. Both sexes had a pouch. The females used theirs for rearing young, and the males used theirs as a protective sheath, covering the external reproductive organs. The animal had a stiff tail and could open its jaws to an unusual extent. Recent studies and anecdotal evidence on its predatory behaviour suggest that the thylacine was a solitary ambush predator specialised in hunting small- to medium-sized prey. Accounts suggest that, in the wild, it fed on small birds and mammals. It was the only member of the genus Thylacinus and family Thylacinidae to have survived until modern times. Its closest living relatives are the other members of Dasyuromorphia, including the Tasmanian devil, from which it is estimated to have split 42–36 million years ago.

Intensive hunting on Tasmania is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributing factors were disease, the introduction of and competition with dingoes, human encroachment into its habitat and climate change. The remains of the last known thylacine were discovered at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 2022. Since extinction there have been numerous searches and reported sightings of live animals, none of which have been confirmed.

The thylacine has been used extensively as a symbol of Tasmania. The animal is featured on the official coat of arms of Tasmania. Since 1996, National Threatened Species Day has been commemorated in Australia on 7 September, the date on which the last known thylacine died in 1936. Universities, museums and other institutions across the world research the animal. Its whole genome sequence has been mapped, and there are efforts to clone and bring it back to life.[12]

- ^ Sleightholme, Stephen R.; Campbell, Cameron R. (30 September 2020). "A Catalogue of the Thylacine captured on film" (PDF). Australian Zoologist. 41 (2): 143–178. doi:10.7882/AZ.2020.032. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

IUCNwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Harris1808was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Paddlewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Geoffroy1810was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Temminck1827was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Grant1831was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Warlow1933was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Anon1859was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Krefft1868was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ De Vis, C. W. (1894). "A thylacine of the earlier nototherian period in Queensland". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 8: 443–447. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ Le Page, Michael (26 October 2024). "De-extinction company claims it has a nearly complete thylacine genome". New Scientist. p. 11.