Titin[5] /ˈtaɪtɪn/ (contraction for Titan protein) (also called connectin) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TTN gene.[6][7] The protein, which is over 1 μm in length,[8] functions as a molecular spring that is responsible for the passive elasticity of muscle. It comprises 244 individually folded protein domains connected by unstructured peptide sequences.[9] These domains unfold when the protein is stretched and refold when the tension is removed.[10]

Titin is important in the contraction of striated muscle tissues. It connects the Z disc to the M line in the sarcomere. The protein contributes to force transmission at the Z disc and resting tension in the I band region.[11] It limits the range of motion of the sarcomere in tension, thus contributing to the passive stiffness of muscle. Variations in the sequence of titin between different types of striated muscle (cardiac or skeletal) have been correlated with differences in the mechanical properties of these muscles.[6][12]

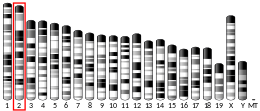

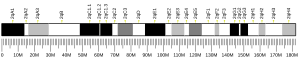

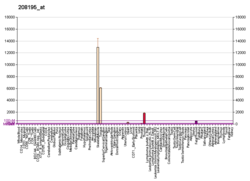

Titin is the third most abundant protein in muscle (after myosin and actin), and an adult human contains approximately 0.5 kg of titin.[13] With its length of ~27,000 to ~35,000 amino acids (depending on the splice isoform), titin is the largest known protein.[14] Furthermore, the gene for titin contains the largest number of exons (363) discovered in any single gene,[15] as well as the longest single exon (17,106 bp).

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000155657 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000051747 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Wang_1979was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "TTN, the human gene for Titin". National Library of Medicine; National Center for Biotechnology Information. April 2018. Archived from the original on 2010-03-07.

- ^ Labeit S, Barlow DP, Gautel M, Gibson T, Holt J, Hsieh CL, et al. (May 1990). "A regular pattern of two types of 100-residue motif in the sequence of titin". Nature. 345 (6272): 273–276. Bibcode:1990Natur.345..273L. doi:10.1038/345273a0. PMID 2129545. S2CID 4240433. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Lee EH. "The Chain-like Elasticity of Titin". Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group, University of Illinois. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Labeit S, Kolmerer B (October 1995). "Titins: giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity". Science. 270 (5234): 293–296. Bibcode:1995Sci...270..293L. doi:10.1126/science.270.5234.293. PMID 7569978. S2CID 20470843. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Minajeva A, Kulke M, Fernandez JM, Linke WA (March 2001). "Unfolding of titin domains explains the viscoelastic behavior of skeletal myofibrils". Biophysical Journal. 80 (3): 1442–1451. Bibcode:2001BpJ....80.1442M. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76116-4. PMC 1301335. PMID 11222304.

- ^ Itoh-Satoh M, Hayashi T, Nishi H, Koga Y, Arimura T, Koyanagi T, et al. (February 2002). "Titin mutations as the molecular basis for dilated cardiomyopathy". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 291 (2): 385–393. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2002.6448. PMID 11846417.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 188840

- ^ Labeit S, Kolmerer B, Linke WA (February 1997). "The giant protein titin. Emerging roles in physiology and pathophysiology". Circulation Research. 80 (2): 290–294. doi:10.1161/01.RES.80.2.290. PMID 9012751.

- ^ Opitz CA, Kulke M, Leake MC, Neagoe C, Hinssen H, Hajjar RJ, Linke WA (October 2003). "Damped elastic recoil of the titin spring in myofibrils of human myocardium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (22): 12688–12693. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10012688O. doi:10.1073/pnas.2133733100. PMC 240679. PMID 14563922.

- ^ Bang ML, Centner T, Fornoff F, Geach AJ, Gotthardt M, McNabb M, et al. (November 2001). "The complete gene sequence of titin, expression of an unusual approximately 700-kDa titin isoform, and its interaction with obscurin identify a novel Z-disc to I-band Linking system". Circulation Research. 89 (11): 1065–1072. doi:10.1161/hh2301.100981. PMID 11717165.