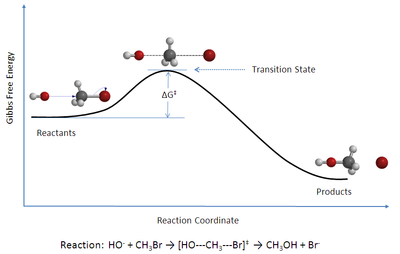

In chemistry, transition state theory (TST) explains the reaction rates of elementary chemical reactions. The theory assumes a special type of chemical equilibrium (quasi-equilibrium) between reactants and activated transition state complexes.[1]

TST is used primarily to understand qualitatively how chemical reactions take place. TST has been less successful in its original goal of calculating absolute reaction rate constants because the calculation of absolute reaction rates requires precise knowledge of potential energy surfaces,[2] but it has been successful in calculating the standard enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡, also written Δ‡Hɵ), the standard entropy of activation (ΔS‡ or Δ‡Sɵ), and the standard Gibbs energy of activation (ΔG‡ or Δ‡Gɵ) for a particular reaction if its rate constant has been experimentally determined (the ‡ notation refers to the value of interest at the transition state; ΔH‡ is the difference between the enthalpy of the transition state and that of the reactants).

This theory was developed simultaneously in 1935 by Henry Eyring, then at Princeton University, and by Meredith Gwynne Evans and Michael Polanyi of the University of Manchester.[3][4][5] TST is also referred to as "activated-complex theory", "absolute-rate theory", and "theory of absolute reaction rates".[6]

Before the development of TST, the Arrhenius rate law was widely used to determine energies for the reaction barrier. The Arrhenius equation derives from empirical observations and ignores any mechanistic considerations, such as whether one or more reactive intermediates are involved in the conversion of a reactant to a product.[7] Therefore, further development was necessary to understand the two parameters associated with this law, the pre-exponential factor (A) and the activation energy (Ea). TST, which led to the Eyring equation, successfully addresses these two issues; however, 46 years elapsed between the publication of the Arrhenius rate law, in 1889, and the Eyring equation derived from TST, in 1935. During that period, many scientists and researchers contributed significantly to the development of the theory.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "transition state theory". doi:10.1351/goldbook.T06470

- ^ Truhlar, D. G.; Garrett, B. C.; Klippenstein, S. J. (1996). "Current Status of Transition-State Theory". J. Phys. Chem. 100 (31): 12771–12800. doi:10.1021/jp953748q.

- ^ M. G. Evans, M. Polanyi (1935), "Some applications of the transition state method to the calculation of reaction velocities, especially in solution", Transactions of the Faraday Society, vol. 31, pp. 875–894, doi:10.1039/tf9353100875, ISSN 0014-7672, retrieved 2024-05-07

- ^ Laidler, K.; King, C. (1983). "Development of transition-state theory". J. Phys. Chem. 87 (15): 2657. doi:10.1021/j100238a002.

- ^ Laidler, K.; King, C. (1998). "A lifetime of transition-state theory". The Chemical Intelligencer. 4 (3): 39.

- ^ Laidler, K. J. (1969). Theories of Chemical Reaction Rates. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Anslyn, E. V.; Dougherty, D. A. (2006). "Transition State Theory and Related Topics". Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books. pp. 365–373. ISBN 1891389319.