| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)ethan-1-amine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 125513 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.464 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties[1] | |

| C10H12N2 | |

| Molar mass | 160.220 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white to orange needles |

| Melting point | 118˚C |

| Boiling point | 137 °C (279 °F; 410 K) (0.15 mmHg) |

| negligible solubility in water | |

| Pharmacology | |

| Intravenous[2][3][4] | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| Very low | |

| Very rapid (oxidative deamination by MAO)[5][6][3][4] | |

| Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | |

| Very rapid[5][6][3][4] | |

| Very short[5][6][3][4] | |

| Very short[5][6][3][4] | |

| Urine[4][7][8] | |

| Legal status |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

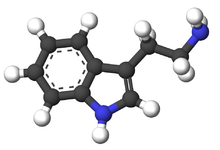

Tryptamine is an indolamine metabolite of the essential amino acid, tryptophan.[9][10] The chemical structure is defined by an indole—a fused benzene and pyrrole ring, and a 2-aminoethyl group at the second carbon (third aromatic atom, with the first one being the heterocyclic nitrogen).[9] The structure of tryptamine is a shared feature of certain aminergic neuromodulators including melatonin, serotonin, bufotenin and psychedelic derivatives such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT), psilocybin, psilocin and others.[11][12][13]

Tryptamine has been shown to activate serotonin receptors[6][14] and trace amine-associated receptors expressed in the mammalian brain, and regulates the activity of dopaminergic, serotonergic and glutamatergic systems.[15][16] In the human gut, symbiotic bacteria convert dietary tryptophan to tryptamine, which activates 5-HT4 receptors and regulates gastrointestinal motility.[10][17][18]

Multiple tryptamine-derived drugs have been developed to treat migraines, while trace amine-associated receptors are being explored as a potential treatment target for neuropsychiatric disorders.[19][20][21]

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85th ed.). CRC Press. p. 3-564. ISBN 978-0-8493-0484-2.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MartinSloan1977was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

ShulginShulgin1997was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f Cite error: The named reference

MartinSloan1970was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Jones1982was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

BloughLandavazoDecker2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

FranzenGross1965was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Price1975was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Tryptamine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Trisha A.; Nguyen, Jason C. D.; Polglaze, Kate E.; Bertrand, Paul P. (2016-01-20). "Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis". Nutrients. 8 (1): 56. doi:10.3390/nu8010056. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 4728667. PMID 26805875.

- ^ Tylš, Filip; Páleníček, Tomáš; Horáček, Jiří (2014-03-01). "Psilocybin – Summary of knowledge and new perspectives". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (3): 342–356. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 24444771. S2CID 10758314.

- ^ Tittarelli, Roberta; Mannocchi, Giulio; Pantano, Flaminia; Romolo, Francesco Saverio (2015). "Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 26–46. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210222409. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 4462041. PMID 26074742.

- ^ "The Ayahuasca Phenomenon". MAPS. 21 November 2014. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mousseau1993was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Khan, Muhammad Zahid; Nawaz, Waqas (2016-10-01). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 83: 439–449. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 27424325.

- ^ Berry, Mark D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Shahid, Mohammed (2017-12-01). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 180: 161–180. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 28723415. S2CID 207366162.

- ^ Bhattarai, Yogesh; Williams, Brianna B.; Battaglioli, Eric J.; Whitaker, Weston R.; Till, Lisa; Grover, Madhusudan; Linden, David R.; Akiba, Yasutada; Kandimalla, Karunya K.; Zachos, Nicholas C.; Kaunitz, Jonathan D. (2018-06-13). "Gut Microbiota-Produced Tryptamine Activates an Epithelial G-Protein-Coupled Receptor to Increase Colonic Secretion". Cell Host & Microbe. 23 (6): 775–785.e5. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.004. ISSN 1931-3128. PMC 6055526. PMID 29902441.

- ^ Field, Michael (2003). "Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (7): 931–943. doi:10.1172/JCI200318326. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 152597. PMID 12671039.

- ^ "Serotonin Receptor Agonists (Triptans)", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31644023, retrieved 2020-10-15

- ^ "New Compound Related to Psychedelic Ibogaine Could Treat Addiction, Depression". UC Davis. 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ ServiceDec. 9, Robert F. "Chemists re-engineer a psychedelic to treat depression and addiction in rodents". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 2020-12-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)