A turbidity current is most typically an underwater current of usually rapidly moving, sediment-laden water moving down a slope; although current research (2018) indicates that water-saturated sediment may be the primary actor in the process.[1] Turbidity currents can also occur in other fluids besides water.

Researchers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute found that a layer of water-saturated sediment moved rapidly over the seafloor and mobilized the upper few meters of the preexisting seafloor. Plumes of sediment-laden water were observed during turbidity current events but they believe that these were secondary to the pulse of the seafloor sediment moving during the events. The belief of the researchers is that the water flow is the tail-end of the process that starts at the seafloor.[1]

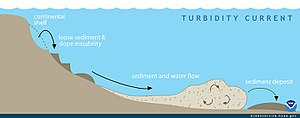

In the most typical case of oceanic turbidity currents, sediment laden waters situated over sloping ground will flow down-hill because they have a higher density than the adjacent waters. The driving force behind a turbidity current is gravity acting on the high density of the sediments temporarily suspended within a fluid. These semi-suspended solids make the average density of the sediment bearing water greater than that of the surrounding, undisturbed water.

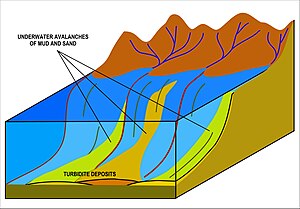

As such currents flow, they often have a "snow-balling-effect", as they stir up the ground over which they flow, and gather even more sedimentary particles in their current. Their passage leaves the ground over which they flow scoured and eroded. Once an oceanic turbidity current reaches the calmer waters of the flatter area of the abyssal plain (main oceanic floor), the particles borne by the current settle out of the water column. The sedimentary deposit of a turbidity current is called a turbidite.

Seafloor turbidity currents are often the result of sediment-laden river outflows, and can sometimes be initiated by earthquakes, slumping and other soil disturbances. They are characterized by a well-defined advance-front, also known as the current's head, and are followed by the current's main body. In terms of the more often observed and more familiar above sea-level phenomenon, they somewhat resemble flash floods.

Turbidity currents can sometimes result from submarine seismic instability, which is common with steep underwater slopes, and especially with submarine trench slopes of convergent plate margins, continental slopes and submarine canyons of passive margins. With an increasing continental shelf slope, current velocity increases, as the velocity of the flow increases, turbulence increases, and the current draws up more sediment. The increase in sediment also adds to the density of the current, and thus increases its velocity even further.

- ^ a b "'Turbidity currents' are not just currents, but involve movement of the seafloor itself". EurekAlert!. Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. 5 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.