| Part of a series on |

| Artificial intelligence |

|---|

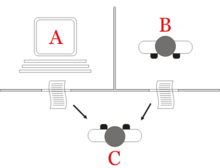

The Turing test, originally called the imitation game by Alan Turing in 1949,[2] is a test of a machine's ability to exhibit intelligent behaviour equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human. Turing proposed that a human evaluator would judge natural language conversations between a human and a machine designed to generate human-like responses. The evaluator would be aware that one of the two partners in conversation was a machine, and all participants would be separated from one another. The conversation would be limited to a text-only channel, such as a computer keyboard and screen, so the result would not depend on the machine's ability to render words as speech.[3] If the evaluator could not reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine would be said to have passed the test. The test results would not depend on the machine's ability to give correct answers to questions, only on how closely its answers resembled those a human would give. Since the Turing test is a test of indistinguishability in performance capacity, the verbal version generalizes naturally to all of human performance capacity, verbal as well as nonverbal (robotic).[4]

The test was introduced by Turing in his 1950 paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" while working at the University of Manchester.[5] It opens with the words: "I propose to consider the question, 'Can machines think?'" Because "thinking" is difficult to define, Turing chooses to "replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words".[6] Turing describes the new form of the problem in terms of a three-person game called the "imitation game", in which an interrogator asks questions of a man and a woman in another room in order to determine the correct sex of the two players. Turing's new question is: "Are there imaginable digital computers which would do well in the imitation game?"[2] This question, Turing believed, was one that could actually be answered. In the remainder of the paper, he argued against all the major objections to the proposition that "machines can think".[7]

Since Turing introduced his test, it has been both highly influential and widely criticized, and has become an important concept in the philosophy of artificial intelligence.[8][9] Philosopher John Searle would comment on the Turing test in his Chinese room argument, a thought experiment that stipulates that a machine cannot have a "mind", "understanding", or "consciousness", regardless of how intelligently or human-like the program may make the computer behave. Searle criticizes Turing's test and claims it is insufficient to detect the presence of consciousness.

- ^ Image adapted from Saygin 2000

- ^ a b (Turing 1950). Turing wrote about the ‘imitation game’ centrally and extensively throughout his 1950 text, but apparently retired the term thereafter. He referred to ‘[his] test’ four times—three times in pp. 446–447 and once on p. 454. He also referred to it as an ‘experiment’—once on p. 436, twice on p. 455, and twice again on p. 457—and used the term ‘viva voce’ (p. 446), see Gonçalves (2023b, p. 2). See also #Versions, below. Turing gives a more precise version of the question later in the paper: "[T]hese questions [are] equivalent to this, 'Let us fix our attention on one particular digital computer C. Is it true that by modifying this computer to have an adequate storage, suitably increasing its speed of action, and providing it with an appropriate programme, C can be made to play satisfactorily the part of A in the imitation game, the part of B being taken by a man?'" (Turing 1950, p. 442)

- ^ Turing originally suggested a teleprinter, one of the few text-only communication systems available in 1950. (Turing 1950, p. 433)

- ^ Oppy, Graham & Dowe, David (2011) The Turing Test Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "The Turing Test, 1950". turing.org.uk. The Alan Turing Internet Scrapbook. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Turing 1950, p. 433.

- ^ Turing 1950, pp. 442–454 and see Russell & Norvig (2003, p. 948), where they comment, "Turing examined a wide variety of possible objections to the idea of intelligent machines, including virtually all of those that have been raised in the half century since his paper appeared."

- ^ Saygin 2000.

- ^ Russell & Norvig 2003, pp. 2–3, 948.