| Title | Director | Format | Info |

|---|---|---|---|

| Looney Tunes Mad as a Mars Hare |

Chuck Jones | Cartoon Series | Bugs Bunny is turned into a "Neanderthal Rabbit" after getting hit by a ray from a time-projector gun by Marvin the Martian. |

| Quest for Fire | Jean-Jacques Annaud | 1981 film | features Neanderthals and a Cro-Magnon attempting to carry a vessel containing fire to the Neanderthal's tribe. |

| Clan of the Cave Bear | Michael Chapman | 1986 film | novel by Jean M. Auel about prehistoric times. It is the first book in the Earth's Children book series |

| Iceman | Fred Schepisi | 1984 film | from a screenplay written by John Drimmer, depicts a frozen Neanderthal coming to life again in the 1980s at an arctic research station. |

| Ghost Light | Andrew Cartmel | 1989 film | an episode in the television series Doctor Who, a Neanderthal called "Nimrod" is the butler of a Victorian era household. |

| Night at the Museum | Shawn Levy | 2006 film | four Neanderthals were put on display in the American Museum of Natural History. An ancient Egyptian tablet, the Tablet of Akhemrah, causes everything on display in the museum to come to life at night. The Neanderthals showed an interest in fire after it was shown to them by the night guard, Larry Daley. |

| The Real Adventures of Jonny Quest | Sherry Gunther | TV series | the mythical yetis are stated to be a relict population of Neanderthals. |

| Dinosaurs | Brian Henson | TV series | Generic "cavemen" have appeared in multiple episodes notably season 3 episodes, "The Discovery," and "Charlene and Her Amazing Humans." |

| You Can't Do That on Television | Geoffrey Darby | TV program | A Neanderthal-like family was a frequent recurring sketch in the children's show, In keeping with the theme of that particular episode, the sketch often parodied modern issues with coarse, overbearing parents outside of a pre-historic cave setting.[1] |

| GEICO Cavemen | Joe Lawson | advertisement | trademarked characters in a series of television advertisements for the auto insurance company GEICO that have aired from 2004 to present, featuring Neanderthal-like cavemen in a modern setting |

| The Croods | Chris Sanders Kirk DeMicco |

2013 animated film | features the titular family as they embark on a journey to find a new home along with a Cro-Magnon boy who has mastered fire and other "technologies" they had never previously encountered. |

| Walking with Beasts | Tim Haines | Documentary | One is charged by a woolly rhinoceros, but escapes, in part because of his stocky constitution. The climax of the episode is when the clan of Neanderthals attack the herd of mammoth as they turn back to the north. |

| Ao: The Last Hunter Ao, le dernier Néandertal |

Jacques Malaterre | prehistoric film | Ao is the protagonist in a 2010 French prehistoric film[2] |

The contemporary perception of Neanderthals and their stereotypical portrayal has its origins in 19th century Europe. Naturalists and anthropologists were confronted with an increasing number of fossilized bones that that did not match any known taxon. Carl Linnaeuss 1758 Systema Naturae in which he had Homo sapiens introduced as a species without diagnosis and description, was the authoritative encyclopedia of the time. The notion of extinct species was unheard of and if so, would have contradicted the paradigm of the immutability of species and the physical world, which was the infallible product of a single and deliberate act of a creator god. Most scholars simply declared the early Neanderthal fossils to be representatives of early "races" of modern man. Thomas Henry Huxley, a future supporter of Darwin's theory of evolution, saw in the Engis 2 fossil a "man of low degree of civilization". The discovery in the Neandertal he interpreted as to be within the range of variation of modern humans.[3]

In mid 19th century Germany biological sciences were dominated by Rudolf Virchow, who described the bones as a "remarkable individual phenomenon" and as "plausible individual deformation".[4] This statement is the reason why the characteristics of the Neanderthals were perceived as a form of pathological skeleton change of modern man in German-speaking countries for many years to come.

August Franz Josef Karl Mayer, an associate of Virchow emphasizes disease, prolonged pain and struggle on comparison with modern human features.[5] "He confirmed the Neanderthal's rachitic changes in bone development[...]. Mayer argued among other things, that the thigh - and pelvic bones of Neanderthal man were shaped like those of someone who had spent all his life on horseback. The broken right arm of the individual had only healed very badly and the resulting permanent worry lines about the pain were the reason for the distinguished brow ridges. The skeleton was, he speculated, that of a mounted Russian Cossack, who had roamed the region in 1813/14 during the turmoils of the wars of liberation from Napoleon."[4]

Arthur Keith of Britain and Marcellin Boule of France, were both senior members of their respective national paleontological institutes and among the most eminent paleoanthropologists of the early 20th century. Both men argued that this "primitive" Neanderthal could not be a direct ancestor of modern man. As a result the museum's copy of the almost complete Neanderthal fossil of La Chapelle-aux-Saints was inaccurately mounted in an exaggerated crooked pose with a deformed and heavily curved spine and legs buckled.[6][7][8][9]

| Northern Canada | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canadian Arctic Tundra | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northern Mainland | Canadian Arctic Archipelago | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern Arctic | Northern Arctic | Arctic Cordillera | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baffin and Torngat Mountains | Ellesmere and Devon Islands Ice Caps | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gulf of Boothia and Foxe Basin Plains | Banks Island and Amundsen Gulf Lowlands | Victoria Island Lowlands | Baffin Uplands | Foxe Uplands | Lancaster and Borden Peninsula Plateaus | Parry Islands Plateau | Ellesmere Mountains and Eureka Hills | Sverdrup Islands Lowland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amundsen Plains | Aberdeen Plains | Central Ungava Peninsula and Ottawa and Belcher Islands | Queen Maud Gulf and Chantrey Inlet Lowlands | Mackenzie and Selwyn Mountains | Peel River and Nahanni Plateaus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source:[10]

| Neanderthal Temporal range: Middle–Late Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

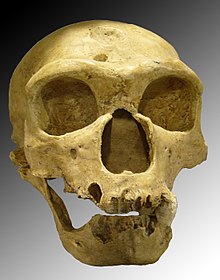

| Neanderthal skull at La Chapelle-aux-Saints | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. neanderthalensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo neanderthalensis King, 1864

| |

| |

| Range of Homo neanderthalensis, that may extend to include the Okladnikov Cave/Altai Mountains and Mamotnaia/Ural Mountains | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Homo mousteriensis hauseri[11] | |

Neanderthals or Neandertals UK: /niˈændərˌtɑːl/, us also /neɪ/-, -/ˈɑːndər/-, -/ˌtɔːl/, -/ˌθɔːl/)[14][15] are an extinct species or subspecies of the genus Homo, that was a close relative of modern humans. Both species occupied a common habitat in Europe for several thousand years. Research has so far no universally accepted conclusive explanation as to what caused the Neanderthal's extinction between 40.000 and 28.000 years ago.[16]

Neanderthal classification has been subject to debate since the discovery of the fdo to this day.[17] Currently two formal species names reflect the ongoing controversy - Homo neanderthalensis the binominal name of a distinct species and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, that classifies Neanderthals as a subspecies of Homo sapiens.[18][19][20]

Sharing a common ancestor of the genus Homo with Homo sapiens, who evolved independently in Africa,[21] the specie's specific morphology developed in Eurasia during the last 350.000 years, reaching its final, "classical Neanderthal" form approximately 130.000 years ago.[22]

Neanderthals left a rich fossil record in the limestone caves of Eurasia, from Western Europe to the Altai Mountains in Central Asia and the Ural Mountains in the North to the Levant in the South.[23] Discoveries include cultural assemblages and Neanderthals are associated with the Mousterian culture, which first appeared approximately 160.000 years ago.[24][25][26]

Generally small and widely dispersed fossil sites suggest, that Neanderthals lived in less numerous and socially more isolated groups than contemporary Homo sapiens. Tools such as Mousterian flint stone flakes and Levallois points are remarkably sophisticated from the outset, yet they have a slow rate of variability and general technological inertia is noticeable during the entire fossil period. Artefacts are of utilitarian nature, symbolic behavioral traits are undocumented before the arrival of modern humans in Europe around 40.000 to 35.000 years ago.[27][28]

The Neanderthal genome sequence was successfully generated in 2010 as the central assignment for the Neanderthal genome project.[29] The DNA structure proved to be 99.7% identical with anatomically modern humans.[30] Subsequently the genetic relationship is being investigated[31][32] and ongoing research has yet helped to interpret and verify kinship lines and interbreeding theories with modern humans and other species of the genus Homo and resulting evolutionary implications.[33][34][35][36]

In 2013 researchers announced that the assemblages of at least 40 widely scattered archaeological sites suggest that Neanderthals intentionally buried their dead.[37] In 2016 a team of researchers found ring structures made of stalagmites fragments inside the Bruniquel Cave, south-western France around 176.000 years old, which were attributed to early Neanderthals. These discoveries might revive the debate on the degree of advancement of Neanderthal's social structure.[38]

- ^ [YCDTOTV.com FAQ "31. Which sets were used for YCDTOTV sketches?" - see "The cave" under Miscellaneous sets. Note: do not correct url formatting as per Wikipedia's Blacklist, June 2010]

- ^ "AO, le dernier Néandertal - site officiel du film". UGC YM. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: On some fossil remains of man. Kapitel 3 in: Evidence as to man's place in nature. D. Appleton and Company, New York 1863

- ^ a b Friedemann Schrenk, Stephanie Müller: Die Neandertaler, S. 16

- ^ Martin Kuckenberg: Lag Eden im Neandertal? Auf der Suche nach dem frühen Menschen. Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf 1997, S. 51, ISBN 3-430-15773-0

- ^ "L'homme fossile de La Chapelle-aux-Saints - full text - Volume VI (p. 11–172), Volume VII (p. 21–56), Volume VIII (p. 1–70), 1911–1913". Royal College of Surgeons of England. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Marcellin Boule - French geologist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Arthur Keith". Royal Anthropological Institute. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "La Chapelle-Aux-Saints - The old man of La Chapelle - The original reconstruction of the 'Old Man of La Chapelle' by scientist Pierre Marcellin Boule led to the reason why popular culture stereotyped Neanderthals as dim-witted brutes for so many years". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "North American Terrestrial Ecoregions—Level III April 2011" (PDF). Commission for Environmental Cooperation. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Wood, Bernard (31 March 2011). Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, 2 Volume Set - edited by Bernard Wood. ISBN 9781444342475. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "Homo sapiens neanderthalensis". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Bibliography of Fossil Vertebrates 1954-1958 - C.L. Camp, H.J. Allison, and R.H. Nichols - Google Books. Books.google.ca. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ "Neanderthal in ODE". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ ""Neanderthal" in Random House Dictionary (US) & Collins Dictionary (UK)". Dictionary.com.

- ^ "Neanderthals' Last Stand Is Traced". The New York Times. September 13, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "WHY DID NEANDERTHALS GO EXTINCT? - ...debate whether Homo neanderthalensis should be classified as a subspecies of Homo sapiens..." Smithsonian Insider. August 11, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Hublin, J. J. (2009). "The origin of Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16022–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616022H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904119106. JSTOR 40485013. PMC 2752594. PMID 19805257.

- ^ Harvati, K.; Frost, S.R.; McNulty, K.P. (2004). "Neanderthal taxonomy reconsidered: implications of 3D primate models of intra- and interspecific differences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (5): 1147–52. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308085100. PMC 337021. PMID 14745010.

- ^ "Scientists Identify Neanderthal Genes in Modern Human DNA". Sci-News.com. January 30, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Liu, Hua; et al. (2006). "A Geographically Explicit Genetic Model of Worldwide Human-Settlement History". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 79 (2): 230–237. doi:10.1086/505436. PMC 1559480. PMID 16826514.

Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is generally interpreted as supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. However, this is where the near consensus on human settlement history ends, and considerable uncertainty clouds any more detailed aspect of human colonization history.

- ^ Currat, M.; Excoffier, L. (November 30, 2004). "Modern Humans Did Not Admix with Neanderthals during Their Range Expansion into Europe - ...morphology developed in Europe during the last 350,000 y under the effect of selection and genetic drift..." PLOS Biology. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Neanderthal ANTHROPOLOGY - ...Neanderthals inhabited Eurasia from the Atlantic regions..." Encyclopaedia Britannica. January 29, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert, eds. (1999). A Dictionary of Archaeology. Blackwell. p. 408. ISBN 0-631-17423-0. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis - ...The Mousterian stone tool industry of Neanderthals is characterized by..." Smithsonian Institution. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Finlayson, C; Pacheco, FG; Rodríguez-Vidal, J; Fa, DA; Gutierrez López, JM; Santiago Pérez, A; Finlayson, G; Allue, E; Baena Preysler, J; Cáceres, I; Carrión, JS; Fernández Jalvo, Y; Gleed-Owen, CP; Jimenez Espejo, FJ; López, P; López Sáez, JA; Riquelme Cantal, JA; Sánchez Marco, A; Guzman, FG; Brown, K; Fuentes, N; Valarino, CA; Villalpando, A; Stringer, CB; Martinez Ruiz, F; Sakamoto, T (October 2006). "Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe". Nature. 443 (7113): 850–3. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..850F. doi:10.1038/nature05195. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16971951. S2CID 4411186.

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis Brief Summary". EOL. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Peresani, M.; Dallatorre, S.; Astuti, P.; Dal Colle, M.; Ziggiotti, S.; Peretto, C. (2014). "Symbolic or utilitarian? Juggling interpretations of Neanderthal behavior: new inferences from the study of engraved stone surfaces". Journal of Anthropological Sciences = Rivista di Antropologia : Jass. 92 (92): 233–255. doi:10.4436/JASS.92007. PMID 25020018. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "A high-quality Neandertal genome sequence". Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Complete Neanderthal genome sequenced: DNA signatures found in present-day Europeans and Asians, but not in Africans, ...showed that Neanderthal DNA is 99.7 percent identical to present-day human DNA ScienceDaily

- ^ Colin P.T. Baillie; University of California, Berkeley. "Neandertals: Unique from Humans, or Uniquely Human?" (PDF). berkeley.edu.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History. "Ancient DNA and Neanderthals". si.edu.

- ^ Sánchez-Quinto, Federico; Botigué, Laura R.; Civit, Sergi; Arenas, Conxita; Ávila-Arcos, María C.; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Comas, David; Lalueza-Fox, Carles (October 17, 2012). "North African Populations Carry the Signature of Admixture with Neandertals". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e47765. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047765. PMC 3474783. PMID 23082212.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

BBCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fu, Qiaomei; Li, Heng; Moorjani, Priya; Jay, Flora; Slepchenko, Sergey M.; Bondarev, Aleksei A.; Johnson, Philip L. F.; Aximu-Petri, Ayinuer; Prüfer, Kay; De Filippo, Cesare; Meyer, Matthias; Zwyns, Nicolas; Salazar-García, Domingo C.; Kuzmin, Yaroslav V.; Keates, Susan G.; Kosintsev, Pavel A.; Razhev, Dmitry I.; Richards, Michael P.; Peristov, Nikolai V.; Lachmann, Michael; Douka, Katerina; Higham, Thomas F. G.; Slatkin, Montgomery; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Reich, David; Kelso, Janet; Viola, T. Bence; Pääbo, Svante (23 October 2014). "Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia". Nature. 514 (7523): 445–449. doi:10.1038/nature13810. hdl:10550/42071. PMC 4753769. PMID 25341783.

- ^ Brahic, Catherine. "Humanity's forgotten return to Africa revealed in DNA", The New Scientist (February 3, 2014).

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (December 16, 2013). "Neanderthals and the Dead". New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ Jaubert, Jacques; Verheyden, Sophie; Genty, Dominique; Soulier, Michel; Cheng, Hai; Blamart, Dominique; Burlet, Christian; Camus, Hubert; Delaby, Serge; Deldicque, Damien; Edwards, R. Lawrence; Ferrier, Catherine; Lacrampe-Cuyaubère, François; Lévêque, François; Maksud, Frédéric; Mora, Pascal; Muth, Xavier; Régnier, Édouard; Rouzaud, Jean-Noël; Santos, Frédéric (2 June 2016) [online 25 May 2016]. "Early Neanderthal Constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in Southwestern France". Nature. 534 (7605): 111–114. doi:10.1038/nature18291. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27251286.