A wetland is a distinct semi-aquatic ecosystem whose groundcovers are flooded or saturated in water, either permanently, for years or decades, or only seasonally. Flooding results in oxygen-poor (anoxic) processes taking place, especially in the soils.[1] Wetlands form a transitional zone between waterbodies and dry lands, and are different from other terrestrial or aquatic ecosystems due to their vegetation's roots having adapted to oxygen-poor waterlogged soils.[2] They are considered among the most biologically diverse of all ecosystems, serving as habitats to a wide range of aquatic and semi-aquatic plants and animals, with often improved water quality due to plant removal of excess nutrients such as nitrates and phosphorus.

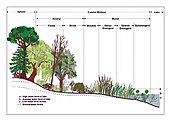

Wetlands exist on every continent, except Antarctica.[3] The water in wetlands is either freshwater, brackish or saltwater.[2] The main types of wetland are defined based on the dominant plants and the source of the water. For example, marshes are wetlands dominated by emergent herbaceous vegetation such as reeds, cattails and sedges. Swamps are dominated by woody vegetation such as trees and shrubs (although reed swamps in Europe are dominated by reeds, not trees). Mangrove forest are wetlands with mangroves, halophytic woody plants that have evolved to tolerate salty water.

Examples of wetlands classified by the sources of water include tidal wetlands, where the water source is ocean tides); estuaries, water source is mixed tidal and river waters; floodplains, water source is excess water from overflowed rivers or lakes; and bogs and vernal ponds, water source is rainfall or meltwater.[1][4] The world's largest wetlands include the Amazon River basin, the West Siberian Plain,[5] the Pantanal in South America,[6] and the Sundarbans in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta.[7]

Wetlands contribute many ecosystem services that benefit people. These include for example water purification, stabilization of shorelines, storm protection and flood control. In addition, wetlands also process and condense carbon (in processes called carbon fixation and sequestration), and other nutrients and water pollutants. Wetlands can act as a sink or a source of carbon, depending on the specific wetland. If they function as a carbon sink, they can help with climate change mitigation. However, wetlands can also be a significant source of methane emissions due to anaerobic decomposition of soaked detritus, and some are also emitters of nitrous oxide.[8][9]

Humans are disturbing and damaging wetlands in many ways, including oil and gas extraction, building infrastructure, overgrazing of livestock, overfishing, alteration of wetlands including dredging and draining, nutrient pollution, and water pollution.[10][11] Wetlands are more threatened by environmental degradation than any other ecosystem on Earth, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment from 2005.[12] Methods exist for assessing wetland ecological health. These methods have contributed to wetland conservation by raising public awareness of the functions that wetlands can provide.[13] Since 1971, work under an international treaty seeks to identify and protect "wetlands of international importance."

- ^ a b Keddy, P.A. (2010). Wetland ecology: principles and conservation (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521519403. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- ^ a b "Official page of the Ramsar Convention". Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ^ Davidson, N.C. (2014). "How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area". Marine and Freshwater Research. 65 (10): 934–941. doi:10.1071/MF14173. S2CID 85617334.

- ^ "US EPA". 2015. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ^ Fraser, L.; Keddy, P.A., eds. (2005). The World's Largest Wetlands: Their Ecology and Conservation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521834049.

- ^ "WWF Pantanal Programme". Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ^ Giri, C.; Pengra, B.; Zhu, Z.; Singh, A.; Tieszen, L.L. (2007). "Monitoring mangrove forest dynamics of the Sundarbans in Bangladesh and India using multi-temporal satellite data from 1973 to 2000". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 73 (1–2): 91–100. Bibcode:2007ECSS...73...91G. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2006.12.019.

- ^ Bange, H. W. (2006). "Nitrous oxide and methane in European coastal waters". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 70 (3): 361–374. Bibcode:2006ECSS...70..361B. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2006.05.042.

- ^ Thompson, A. J.; Giannopoulos, G.; Pretty, J.; Baggs, E. M.; Richardson, D. J. (2012). "Biological sources and sinks of nitrous oxide and strategies to mitigate emissions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 367 (1593): 1157–1168. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0415. PMC 3306631. PMID 22451101.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

clewell2013was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

mitsch2007was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Davidson, N.C.; D'Cruz, R. & Finlayson, C.M. (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Wetlands and Water Synthesis: a report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (PDF). Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. ISBN 978-1-56973-597-8.

- ^ Dorney, J.; Savage, R.; Adamus, P.; Tiner, R., eds. (2018). Wetland and Stream Rapid Assessments: Development, Validation, and Application. London; San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-805091-0. OCLC 1017607532.