1,000,000,000 edits, board elections, virtual Wikimania 2021

Edit number 1,000,000,000

Ser Amantio di Nicolao is already well known for being the "most productive editor" on the English language Wikipedia in terms of the number of edits he has made. This month, he added "the billionth edit" made by all editors on enWiki to his laurels. The count was complicated by a change in software and other factors – so let's say it was the billionth edit since the counter was reset in 2002.

The article he edited was Death Breathing and it was later converted to a redirect. He told The Signpost "Getting the billionth edit wasn't actually my goal, though it's certainly a nice lagniappe – all I had been trying to do was to push us closer to the goal itself, so that we could hopefully clear it before the twentieth anniversary of Wikipedia on January 15. It was quite a shock to discover that I'd hit the magic number. The article itself holds no particular interest for me – my musical interests lie more in the direction of classical. It was just one of a large handful of articles to which I was adding authority control templates. Nothing special."

He explained the personal significance of the achievement with a story. "Not long before my mother left the Soviet Union, her employer, Leningrad State University, got a copier for use in the office. It was a revolutionary tool; previously, office staff had relied on mimeographing and typing to perform many of the tasks the copier would take over. The powers-that-be knew that the new machine could be dangerous in the wrong hands, and restricted access to it. Only the departmental secretary could let people in to use it. And they had to be witnessed while they were making their copies. My mother never used this miracle machine, but when she heard about it her first thought was: 'This is it. This marks the beginning of the end of Soviet power.'"

"Just like the paper copies in Leningrad, each of the billion edits on Wikipedia, no matter how insignificant, is another step in ensuring that knowledge, and learning, and freedom, can be made available to all. That's the force of this moment in Wikipedia's history. The cumulative effect of those billion edits shows me just how far we have managed to come, collectively, in changing the world. 'As ordinary as it all appears,' to borrow a line from Jhumpa Lahiri, 'there are times when it is beyond my imagination.' "

Foundation removes community elections from bylaws, calls for feedback on future process for "community-and-affiliate-selected" trustees

The Board of Trustees has approved a bylaw change to increase the number of trustees from a maximum of 10 up to a maximum of 16 with 8 seats to be "community-and-affiliate-selected". The minimum number of seats is 9. As a step to ensure that the balance will not favor board-appointed seats, the Board will not make an appointment if that appointment will result in a minority of "community-and-affiliate-selected" seats.

In the announcement, the board's chair remarks that "We have not used the term 'community-sourced' that we initially proposed and instead now call these 'community-and-affiliate-selected' seats." According to a three-way diff prepared by a community member, the change otherwise largely implements the revision that the board had published for feedback in October (see our detailed earlier report). In particular, it still removes the requirement that a certain number of trustees have to be "selected from candidates approved through community voting," replacing it with the wording "sourced from candidates vetted through a Community and/or Affiliate nomination process" (also combining the board seats selected by editor community with those selected by affiliates, i.e. chapters and other recognized organizations within the Wikimedia movement). With this change, the board aims for "a process that enables diverse and equitable representation from communities across the Wikimedia movement." It is also likely to help the board avoid situations like the community re-electing a community-selected trustee despite the rest of the board having dismissed him not long before.

The removal of "voting" had been controversial, with founder trustee Jimmy Wales objecting that "I will personally only support a final [bylaws] revision which explicitly includes community voting". However, the December 9 resolution approving the change was unanimous. On the other hand, the announcement notes that "the status of Jimmy Wales as Community Founder Trustee remains unchanged" – after the October consultation, the board had taken up a proposal to remove his position (see earlier coverage: "WMF Board considering the removal of Jimmy Wales' trustee position amid controversy over future of community elections").

How are the community seats to be selected? We don't know yet! You can comment on an appropriate method at Call for feedback: Community Board seats from February 1 to March 14.

Wikimania 2021 going virtual

Last year's Wikimania scheduled for Bangkok was originally delayed to 2021 because of the pandemic. This week the in-person 2021 Wikimania was cancelled in favor of a virtual event. Janeen Uzzell announced on the Wikipedia-l mailing list that "it seems unlikely that we will all be able to travel freely and convene together by August 2021". Planning for the virtual Wikimania will begin soon and comments are welcomed at Talk:Wikimania 2021 on Meta.

Brief notes

- New administrators: The Signpost welcomes the English Wikipedia's newest administrator, Hog Farm. In 2020, 17 new administrators were approved by the community out of 25 nominations.

- The 2020 Annual Report for the MediaWiki Stakeholders' Group was published.

- Edit-a-thon: An online Wikipedia edit-a-thon organised by the Berlin chapter of Tech Workers Coalition will be held February 19-21, 2021 to improve coverage of trade unions, works councils and labour disputes in the tech industry. They hope to improve articles such as Amazon worker organization, Google worker organization and Platform economy. See the event page at Wikipedia:WikiProject Organized Labour/Online edit-a-thon Tech February 2021.

Wiki reporting on the United States insurrection

Two weeks before Donald Trump's presidency ended, one of its defining moments appeared in near real time on the pages of Wikipedia. Our article on the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol was created as rioters were overwhelming Capitol security, shots were reported on Wikipedia 30 minutes after they were fired, and the inevitable conclusion, the affirmation of Joe Biden's election as president of the United States, was recorded on our pages an hour after it was recorded in Congress.

At 1:10 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on January 6, Donald Trump ended his speech in which he repeated the false claims that he had won the presidential election, and instructed his supporters to march to the Capitol. "After this, we’re going to walk down and I’ll be there with you," he promised, although he never would join them. Among the protesters were people who took to heart Trump's statement that "If you don't fight ... you're not going to have a country anymore". At 1:26 p.m., Capitol police ordered the evacuation of two buildings in the Capitol complex as the gathering crowd continued to swell, and rioters began to overwhelm those guarding the plaza.

Meanwhile, Another Believer looked on. He'd worked on several similar articles, both pro- and anti-Trump marches, including March 4 Trump, Mother of All Rallies, LGBT protests against Donald Trump, Women's March on Portland and Not My Presidents Day. This day he watched as Trump gave his speech on the Ellipse, instructing his supporters to converge on the Capitol. It was when Another Believer heard that evacuations had been ordered in the Capitol complex that he became confident that this was not just another unbelievable but ultimately non-notable event in a presidency full of unprecedented chaos. At 1:34 p.m. he hit publish on the first draft of what would later be titled 2021 storming of the United States Capitol. It began as a one-sentence stub: "On January 6, 2021, thousands of Donald Trump supporters gathered in Washington, D.C. to reject results of the November 2020 presidential election."

By 2:30 p.m., when I became the second editor of the article, it was three sentences long, with three references, and three "see also" entries. The last two sentences were "At least 10 people have been arrested. Select buildings in the Capitol Hill complex were evacuated."

When I joined Another Believer editing the page, neither of us knew that about fifteen minutes earlier, rioters had broken windows in the Capitol building, climbed through, and unlocked doors to allow a surge of people to breach the Capitol. The first editor to report this did so at 2:33 p.m., and as rioters began to flood into the Capitol, edits began to flood in to the article as Wikipedians attempted to document the breaking news event in close to real time. Before too long, a new edit to the page was being saved every ten seconds. At 2:49 p.m., a Wikidata item was created to record structured data about the event, and by 3 p.m. editors on the Arabic and Basque Wikipedias had created pages of their own.

Shortly before 3 p.m., reports began to trickle in that shots had been fired inside the Capitol building. The first reports came from unreliable sources: Twitter posts, many of which also showed photographs of Capitol police gathered with guns drawn at the doors to the U.S. House of Representatives. By 3 p.m., ABC News confirmed, and it was added to the article less than fifteen minutes later. The first page move happened around the same time, when an editor observed that the page title, "January 2021 Donald Trump rally", did not disambiguate the event from other Donald Trump rallies that month. The page remained at its new title, "January 2021 United States Capitol protests", until a requested move discussion with more than 200 participants over 12 hours closed in the early hours of January 7 with consensus to move the page to "2021 storming of the United States Capitol".

The page continued to change at breakneck speed throughout the afternoon. By 4 p.m. a total of 257 edits had been made, 206 in the previous hour. Discussions unfurled on the talk page as hundreds of editors worked to craft the page. Should "parties to the civil conflict" be represented in the infobox, or was that too militaristic? Should various leaders' comments tweets about the event be included in a "reactions" section on the page, and if so should flag icons be used to denote their nationality? Should the people at the Capitol be called a mob, rioters, protesters, insurrectionists, or something else, and should that name differ based on whether they entered the building or stayed outside it?

At around 5:40 p.m., law enforcement announced they had cleared the Senate building. By this time, the page was 1,800 words long. People had begun looking for freely licensed images and videos with which to illustrate the page, and the first image appeared in the article at 6:36 p.m. By the end of the day, over 1,000 edits had been made to create a page that was more than 4,000 words long.

As of January 31, 1,084 editors have collaborated to create a page that has been viewed over 2.7 million times. The article is more than 12,000 words long and cites 475 unique references. The talk page is up to twelve pages of archived discussion, and a new move discussion continues as editors deliberate over whether the page ought to be retitled "Insurrection at the United States Capitol". Articles about auxiliary topics too long to fit in the main page have been created to describe the timeline, domestic and international reactions, and aftermath of the event. The article exists on 55 language versions of Wikipedia, and there are entries about the topic at French and Russian Wikinews and English and Italian Wikiquote. Hundreds of images and videos have been uploaded to Category:2021 storming of the United States Capitol and its subcategories on Wikimedia Commons.

Breaking news editing on Wikipedia often reminds me of the myth about bumblebees, which holds that bumblebees are able to fly despite being scientifically unable to do so. That thousands of editors can work together, communicating only through edit summaries and talk page messages, to accurately and comprehensively document breaking news as it unfolds seems to be something that could never work in theory. But in practice, it is nothing short of remarkable that we are able to sift through inaccurate and sometimes contradictory news reports to separate the facts from the inevitable inaccuracies and hyperbole of breaking news, make our best guesses at what will have lasting notability, and, eventually, revisit the articles once time has passed to ensure they are complete and balanced.

From Anarchy to Wikiality, Glaring Bias to Good Cop: Press Coverage of Wikipedia's First Two Decades

- Media coverage of Wikipedia has radically shifted over the past two decades: once cast as an intellectual frivolity, it is now lauded as the "last bastion of shared reality" online. To increase diversity and digital literacy, journalists and the Wikipedia community should work together to advance a new "wiki journalism."

- Omer Benjakob is a journalist and researcher focused on Wikipedia and disinformation online. He is the tech and cyber reporter and editor for Haaretz and his work has appeared in Wired UK as well as academic publications.

- Stephen Harrison is an attorney and writer whose writings have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Wired, and The Atlantic. He writes the Source Notes column for Slate magazine about Wikipedia and the information ecosystem.

- This article has been updated from a version published on November 16, 2020 by Wikipedia @ 20 and is licensed CC BY 4.0.

Introduction

Wikipedia and its complex array of policies and intricate editorial processes are frequently misunderstood by the media. However, these very same processes – which seem convoluted if not impenetrable to outsiders not versed in the nuanced minutiae of Wikipedic culture – are many times the key to its encyclopedic success.

For example, Wikipedia's main article for Wikipedia, one of the most important (as well as most edited) articles on the project, explains that the ability to lock pages and prevent anonymous public editing on the encyclopedia that anyone can edit was the key to Wikipedia's success in weeding out disinformation on the coronavirus. Citing a respected media source, Wikipedia's Wikipedia article explains: "A 2021 article in the Columbia Journalism Review identified Wikipedia's page protection policies as '[p]erhaps the most important' means at Wikipedia's disposal to 'regulate its market of ideas'".[1] The article in the Columbia Journalism Review was written by us, in wake of research we conducted for the book Wikipedia @ 20 published by the MIT Press and edited by Joseph Reagle and Jackie Koerner this year. The mutually affirming relationship between Wikipedia and the media, as exemplified by our CJR story and the role it plays on the Wikipedia article, is only the latest in a long line spanning 20 years. Increasingly, journalists covering Wikipedia like us (Omer Benjakob for Haaretz and Stephen Harrison for Slate, among others) have found our articles about Wikipedia being quoted as sources on Wikipedia's articles. However, this circular relationship between sources and the sourcers, the cited and the citers, is a hallmark of Wikipedia and its community's somewhat volatile relationship with popular media over the years.

The following is an attempt to map out the different stages of those ties over the years as well as to glean from them real conclusions to help improve them. In the end we lay out what we think are small yet key steps that can be taken by journalists, Wikipedians and the Wikimedia Foundation to help improve the public's understanding of the project. While our research for MIT Press was intended for the academic community and the WMF, and while the CJR article was focused on journalists and how they can improve their coverage of Wikipedia, this text for The Signpost is aimed at the Wikipedian community.

Diverse and divergent as human society itself, one can never truly generalize about those involved in editing Wikipedia. However, to improve the public's ability not just to understand Wikipedia's process but also participate in it and provide critical oversight of the world's leading source of knowledge also requires openness to change, forgiveness for miscommunications and most importantly: good-faith. Good-faith not just towards your fellow Wikipedians, but also those not yet involved in it, or perhaps making their first foray into Wikipedia's processes, either as journalists – or as would-be first-time editors (who are sometimes responding to what they view as an encyclopedic injustice revealed by a journalist).

We as reporters trying to explain Wikipedia outwardly have many times been met with apprehension if not suspicion by members of the community, reluctant to air internal grievances publicly, and perhaps even risk facing accusations of off-wiki canvassing. Many times, we as journalists have been told to "fix" Wikipedia instead of write about it. This position is of course understandable. However, it misses both the wider role Wikipedia and journalism play in society. Wikipedia is a volunteer-community-run project, but it does not belong exclusively to the community.

Though everyone can participate, without proper media oversight there is no realistic way to expect people to find their place within the sprawling Wikipedic world of projects, task forces, associations and even faux-cabals. The following is an attempt to stress the mutually affirming ties Wikipedia and its community have had with the media, with the explicit attempt of helping to forge a new path for them, one in which journalists accurately portray the community, but also one in which the community works with journalists to help them navigate the halls of online encyclopedic power.

Four phases

"Jimmy Wales has been shot dead, according to Wikipedia, the online, up-to-the-minute encyclopedia." That was the opening line of a blatantly false 2005 news report by the online magazine The Register.[2] Rather than being an early example of what we may today call "fake news", the report by the tech site was a consciously snarky yet prescient criticism of Wikipedia and its reliability as a source for media. Wales was still alive, of course, despite what it had briefly stated on his Wikipedia entry, but by attributing his death to English Wikipedia, The Register sought to call out a perceived flaw in Wikipedia: On Wikipedia, truth was fluid and facts were exposed to anonymous vandals who could take advantage of its anyone-can-edit model to spread disinformation.

Over the past twenty years, English Wikipedia has frequently been the subject of media coverage, from in-depth exposés to colorful features and critical Op-eds. Is Wikipedia "impolite" as The New York Times claimed, or rather a "ray of light" as The Guardian suggested?[3] Both of us are journalists who have regularly covered Wikipedia in recent years, and before that we were frequent consumers of knowledge on the site (like many of our journalist colleagues). Press coverage of Wikipedia during the past 20 years has undergone a dramatic shift, and we believe it's important to highlight how the media's understanding of Wikipedia has shifted along with the public's understanding. Initially cast as the symbol of intellectual frivolity in the digital age, Wikipedia is now being lauded as the "last bastion of shared reality" in Trump's America.[4] Coverage, we claim, has evolved from bewilderment at the project, to concern and hostility at its model, to acceptance of its merits and disappointment at its shortcomings, and finally to calls to hold it socially accountable and reform it like any other institution.

We argue that press coverage of Wikipedia can be roughly divided into four periods. We have named each period after a major theme: "Authorial Anarchy" (2001–2004/5); "Wikiality" (2005–2008); "Bias" (2011–2017); and "Good Cop" (2018–present). We note upfront that these categories are not rigid and that themes and trends from one period can and often do carry over into others. But the overall progression reveals how the dynamic relationship between Wikipedia and the press has changed since its inception, and might provide further insight into how the press and Wikipedia will continue to interact with each other in the internet's knowledge ecosystem.

In short, we argue for what we term "wiki journalism" and the need for media to play a larger role in improving the general public's "Wikipedia literacy". With the help of the Wikimedia Foundation and the Wikipedia community, the press, we claim, can play a more substantial role in explaining Wikipedia to the public and serving as a civilian watchdog for the online encyclopedia. Encouraging critical readership of Wikipedia and helping to increase diversity among its editorship will ensure greater public oversight over the digital age's preeminent source of knowledge.

Authorial anarchy (2001–2004/5)

When Wikipedia was launched in 2001, mainstream media as well as more technology minded outlets treated it as something between a fluke and quirky outlier. With quotes from co-founders Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger, early coverage tended to focus on what seemed like Wikipedia's most novel aspects: how it is written by anyone, edited collaboratively, is free to access and, in the case of tech media, extends the culture of open software development to the realm of encyclopedias.

"Anyone who visits the site is encouraged to participate," The New York Times wrote in its first piece on Wikipedia, titled "Fact-Driven? Collegial? This Site Wants You." Reports like these laid out the basic tenets of English Wikipedia, focusing on how collaborative technology and the volunteer community regulated what was termed "authorial anarchy."[5] Many of these reports included a colorful lede ("What does Nicole Kidman have in common with Kurt Godel?" Both have Wikipedia articles) showcasing the quirky diversity of content on the new site, where "[y]ou don't even have to give your real name" to contribute.[6]

Despite Wales' lofty claims that Wikipedia was creating a world in which everyone could have "free access to the sum of all human knowledge", throughout the early 2000s, mainstream media remained skeptical towards Wikipedia.[7] Reports from 2002–2003 mostly documented with some surprise its rapid growth in scale and scope, as well as its expansion into other languages. MIT Technology Review ran a report called "Free the Encyclopedias!", which described Wikipedia as "intellectual anarchy extruded into encyclopedia form" and "a free-wheeling Internet-based encyclopedia whose founders hope will revolutionize the stodgy world of encyclopedias"[6] – then still dominated by the Enlightenment-era Britannica and its more digital savvy competitor Encarta.

Repeated comparison to Encarta and Britannica is perhaps the most prominent characteristic of early media coverage, one that will disappear in later stages as Wikipedia cements its status as a legitimate encyclopedia. MIT Technology Review, for example, unironically claimed that Wikipedia "will probably never dethrone Britannica, whose 232-year reputation is based upon hiring world-renowned experts and exhaustively reviewing their articles with a staff of more than a hundred editors".[6] The demise of the status of experts would later become a hallmark of coverage of Wikipedia (discussed in the next section), but its seeds can be found from the onset: For example, in its first exposé on Wikipedia in 2004, The Washington Post reported that Britannica's vaunted staff was now down to a mere 20 editors. Only a year prior, Wikipedia editors noted that the prestigious paper "brushed off" Wikipedia almost entirely and instead focused on CD-ROM encyclopedias[8] – all the rage since Encarta launched a decade earlier, mounting what seemed at the time to be the bigger threat towards Britannica. Within a year, however, the newspaper's take on Wikipedia changed dramatically, and it was now concerned by the long term effect of Wikipedia's success, suggesting "the Internet's free dissemination of knowledge will eventually decrease the economic value of information".[8]

At the end of 2005, this tension between the English encyclopedia of the Enlightenment and that of the digital age would reach its zenith in a now infamous Nature news study that compared Wikipedia and Britannica. Published in December of 2005, Nature's "Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head" found Wikipedia to be as accurate as its Enlightenment-era competitor, bringing experts to compare randomly selected articles on scientific topics.[9] News that Wikipedia successfully passed scientific scrutiny – that its ever-changing content was deemed to be as reliable as the static entries of a vaunted print-era encyclopedia like Britannica – made headlines around the world.[10] The Nature study was the final stage in a process that peaked in 2005 and cemented Wikipedia's shift from a web novelty whose value was to be treated skeptically at best to a cultural force to be reckoned with.

In March of 2005, Wikipedia had crossed the half a million article mark and some intellectuals began to discuss the "the wikification of knowledge".[11]

Tellingly, 2005 was also the year that the Wikipedia community first began recording its coverage in the media in an organized fashion. Initially focused on instances of "Wiki love" from the press, in 2005 the community created categories and project pages like "America's Top Newspapers Use Wikipedia" for its early press clippings.[12] The Signpost, the online newspaper for the English language Wikipedia, was also founded in 2005 to report on events related to Wikipedia.[13] Over time the community grew increasingly conscious of its public role and by 2006 an organized index of all media references to Wikipedia was set up – first with a list for every year and then, as coverage swelled, one for every month as well.[14] Categories were also created for times when Wikipedia was cited as a source of information by mainstream media[15] – a rare reversal of roles that highlighted the mutually affirming relationship between Wikipedia and the media that would develop over later periods.

Indeed, 2005 was to be a key year for Wikipedia: it saw its biggest vindication – the Nature report – alongside its biggest vilification – the so-called Seigenthaler affair. By 2005, Wikipedia was no longer quirky. Now it was to be viewed within a new framework which contrasted its popularity with its accuracy and debated the risks it posed. The New York Times, for example, claimed that the Seigenthaler "case triggered extensive debate on the Internet over the value and reliability of Wikipedia, and more broadly, over the nature of online information".[16] In the next phase, Wikipedia's effect on the popular understanding of truth that would be the overriding theme.

Wikiality (2005–2008)

Stephen Colbert launched his satirical news program The Colbert Report with a segment dedicated to what would be dubbed 2005's word of the year: truthiness.[17] "We're not talking about truth, we're talking about something that seems like truth – the truth we want to exist", Colbert explained.[18] He even urged viewers to take the truth into their own hands and "save" the declining populations of elephants in Africa by changing their numbers on Wikipedia, causing its server to crash. The wider point resonated.[19] "It's on Wikipedia, so it must be true", The Washington Post wrote that year.[20] Wikipedia was no longer taken to be just another website, it was now a powerhouse undermining intellectual institutions and capable of changing our very perception of reality.

Colbert followed up his infamous segment with another potent neologism: wikiality. "Wikiality", he charged, was the reality created by Wikipedia's model, in which "truth" was based on the will of the majority and not on facts. This was a theme that had a deep political resonance in post-9/11 America, buoyed by the presidency of George W. Bush and the rise to prominence of Fox News – and Wikipedia was increasingly cast as providing its underlying intellectual conditions. "Who is Britannica to tell me that George Washington had slaves? If I want to say he didn't, that's my right," Colbert charged. "Thanks to Wikipedia, it's also a fact. [We're] bringing democracy to knowledge."[21]

During 2006–2009, the dominance of Wikipedia's encyclopedic model was solidified. In 2008, The New York Times published a "eulogy" for print encyclopedia and flagged the need to understand the "epistemology of Wikipedia" and the "wikitruth" it bred.[22] Wikipedia's underlying philosophy – its model's effects on the very nature of facticity – was now deserving of more serious and critical examination. MIT Technology Review ran a piece on "Wikipedia and the Meaning of Truth", asking "why the online encyclopedia's epistemology should worry those who care about traditional notions of accuracy".[23]

Concerns that Wikipedia's epistemic model was replacing expertise loomed large: In 2006, The New York Times debated the merits of "the nitpicking of the masses vs. the authority of the experts", and The Independent asked: "Do we need a more reliable online encyclopedia than Wikipedia?"[24] In a report that profiled Wikipedians, The New Yorker wondered: "Can Wikipedia conquer expertise?"; and Larry Sanger, who had left the project by then, lamented "the fate of expertise after Wikipedia".[25] Though largely negative, these in-depth reports also permitted a more detailed treatment of Wikipedia's theory of knowledge. Articles like Marshal Poe's "The Hive", published in The Atlantic's September 2006 edition, laid out for intellectual readers Wikipedia's history and philosophy like never before.

Epistemological and social fears of Wikipedia were also fueled by Wikipedia's biggest public media storm to date – the so-called Essjay scandal of 2007.[26] It even spurred calls to reform Wikipedia.[27] The fact that Ryan Jordan held an official status within Wikipedia's community seemed to echo an increasingly accepted political truism: facts were being manipulated by those with power.

Knowledge was increasingly being politicized and the entirety of Capitol Hill was banned from editing Wikipedia anonymously during 2006 after politicians' articles were whitewashed in what The Washington Post called "wikipolitics".[28] During this period Wikipedia also first faced allegations of having a liberal bias – for example by "evangelical Christians" who opened a conservative wiki of their own.[29] Reports like these helped grant social currency to the claim that knowledge was political like never before.

The politicization of knowledge, alongside a proliferation of alternative wikis – exacerbated in part by Wales' for-profit website Wikia, launched in 2006 – all served to highlight the wikiality of America's political and media landscape.[30] It was at this time that the first cases of "citogenesis" – circular and false reporting originating from Wikipedia – appeared. These showed how dependent classic media was on Wikipedia – and therefore how politically vulnerable and unreliable it was by proxy. These included reports that cited the unfounded claim regarding Hillary Clinton being the valedictorian of her class at Wellesley College, an error born from false information introduced to her Wikipedia article.[31] The edit wars on Bush's Wikipedia page highlighted the online encyclopedia's role in what The New York Times termed the "separate realities" within America.[32]

By 2007, Wikipedia was among the top ten most popular websites in the world. And though it was a non-profit, it maintained partnerships with corporate juggernauts like Google, whose donations and usage of Wikipedia helped it walk among giants, giving it a privileged position on the search engine results and sparking concerns of a "googlepedia" by internet thinkers.[33]

Wikipedia was now a primary source of knowledge for the information age, and its internal workings mattered to the general public.[34] Coverage shifted in accordance. Reports began to focus on the internal intellectual battles raging within the community of editors: For example, The Guardian wrote about the ideological battle between "deletionists" and "inclusionists".[35] For the first time, coverage of Wikipedia was no longer monolithic and the community was permitted diverging opinions by the press. Wikipedia was less a unified publisher and more a vital discursive arena. Policy changes were debated in the media, and concerns over Wikipedia's "declining user base" were also covered – mostly by Noam Cohen, who covered the encyclopedia for the New York Times.[36] Wikipedia was now a beat. Its worldview was now fully embedded within our social and political reality. The question was what was it telling us, who was writing it, and who was being excluded.

Bias (2011–2017)

In February 2011, The New York Times ran a series of articles on the question "Where Are the Women of Wikipedia?" in its opinion pages. These 2011 articles have very different headlines than the paper's coverage of Wikipedia in the prior decade. Reporting between roughly the years 2006 to 2009 focused on Wikipedia's reliability, with headlines like "Growing Wikipedia Refines its ‘Anyone Can Edit' Possibility" (2006) and "Without a Source, Wikipedia Can't Handle the Truth" (2008).[37]

By 2011, however, the press coverage had zeroed in on the site's gender imbalance. Headlines were much more openly critical of the community itself than in the past, with The New York Times' series calling out "trolls and other nuisances" and Wikipedia's "antisocial factor," as well as "nerd avoidance".[38] Press coverage had shifted from the epistemological merits of Wikipedia to legitimate concerns about bias in its contributor base.

The 2011 series about gender on Wikipedia followed a 2010 survey conducted by United Nations University and UNU-MERIT that indicated only 12.64 percent of Wikipedia contributors were female among the respondents.[39] Although the results of that study were later challenged,[40] much like with Nature's study, the fact that its results were contested by Britannca made little difference. The fact that the UN study received an entire series of articles indicates how the results struck a cultural nerve. What did it say about Wikipedia–and internet knowledge generally – that a disproportionate number of the contributors were men?

One could argue that this shift – from grappling with underpinnings of Wikipedia's model of knowledge production to a critique of the actual forces and output of the wiki way of doing things – symbolized an implicit acceptance of Wikipedia's status in the digital age as the preeminent source of knowledge. Media coverage during this period no longer treated Wikipedia as an outlier, a fluke, or as an epistemological disaster to be entirely rejected. Rather, the press focused on negotiating with Wikipedia as an existing phenomena, addressing concerns shared by some in the community – especially women, predating the GamerGate debate of 2014.

Press coverage of Wikipedia throughout the period of 2011 to roughly 2017 largely focused on the online encyclopedia's structural bias. This coverage also differed markedly from previous years in its detailed treatment of Wikipedia's internal editorial and community dynamics. The press coverage highlighted not only the gender gap in percentage of female contributors, but in the content of biographical articles, and the efforts by some activists to change the status quo. Publications ranging from The Austin Chronicle to The New Yorker covered feminist edit-a-thons, annual events to increase and improve Wikipedia's content for female, queer, and women's subject, linking contemporary identity politics with the online project's goal of organizing access to the sum of human knowledge.[41] In addition to gender, the press covered other types of bias such geographical blind spots and the site's exclusion of oral history and other knowledge that did not meet the Western notions of verifiable sources.[42]

During this period, prestigious publications also began profiling individual Wikipedia contributors, giving faces and names to the forces behind our knowledge. "Wikipedians" were increasingly cast as activists and recognized outside the community. The Washington Post, for example, covered Dr. Adrianne Wadewitz's death in 2014, noting that Wadewitz was a "Wikipedian" who had "empower[ed] everyday Internet users to be critical of how information is produced on the Internet and move beyond being critical to making it better".[43] The transition from covering Wikipedia's accuracy to covering Wikipedians themselves perhaps reflects an increased concern with awareness about the human motivations of the people contributing knowledge online. Many times this took on a humorous tone, like the case of the "ultimate WikiGnome" Bryan Henderson whose main contribution to Wikipedia was deleting the term "comprised of" from over 40,000 articles.[44] Journalists (including the authors of this paper) have continued this trend of profiling Wikipedians themselves.

A 2014 YouGov study found that around two thirds of British people trust the authors of Wikipedia pages to tell the truth, a significantly higher percentage than those who trusted journalists.[45] At the same time, journalists were increasingly open to recognizing how crucial Wikipedia had become to their profession: With the most dramatic decline in newsroom staffs since the Great Recession, Wikipedia was now used by journalists for conducting initial research[46] –another example of the mutually affirming relationship between the media and Wikipedia.

As more journalists used and wrote about Wikipedia, the tone of their writing changed. In one of his reports for The New York Times, Noam Cohen quoted a French reporter as saying, "Making fun of Wikipedia is so 2007".[47] When Cohen first began covering Wikipedia, most people saw Wikipedia as a hobby for nerds–but that characterization had by now become passé. The more pressing concern, according to Cohen, was "[s]eeing Wikipedia as The Man".[47]

Overall, press coverage of Wikipedia during this period oscillates between fear about the site's long-term existential prospects[48] and concern that the site is continuing the masculinist and Eurocentric biases of historical encyclopedias. The latter is significant, as it shows how Wikipedia's pretenses of upending the classic print-model of encyclopedias have been accepted by the wider public, which, in turn, is now concerned or even disappointed that despite its promise of liberating the world's knowledge from the shackles of centralization and expertise, it has in fact recreated most of the biases of yesteryear.

Good Cop (2018–present)

In April 2018, Cohen wrote an article for The Washington Post titled "Conspiracy Videos? Fake News? Enter Wikipedia, the 'Good Cop' of the Internet."[49] For more than a decade, Cohen had written about Wikipedia in the popular press, but his "Good Cop" piece was perhaps his most complimentary and it signaled a wider change in perception regarding Wikipedia. He declared that "fundamentally … the project gets the big questions right." This would become the main theme of coverage and by the time Wikipedia marked its 20th anniversary, most main stream media sources were gushing with what the community in 2005 called "wiki love" for the project.

Cohen's "Good Cop" marks the latest shift in coverage of Wikipedia, one that embarks from the issue of truthiness and reexamines its merits in the wake of the "post-truth" politics and "fake news" – 2016 and 2017's respective words of the year.

The Wall Street Journal credited Wikipedia's top arbitration body, ArbCom, with "keep[ing] the peace at [the] internet encyclopedia."[50] Other favorable headlines from 2018 and 2019 included: "There's a Lot Wikipedia Can Teach Us About Fighting Disinformation" and "In a Hysterical World, Wikipedia is a Ray of Light – and That's the Truth."[51] Wikipedia was described by The Atlantic as "the last bastion of shared reality" online, and for its 18th birthday, it was lauded by The Washington Post as "the Internet's good grown up."[52]

But this was only the beginning. What caused press coverage of Wikipedia to pivot from criticizing the encyclopedia as the Man to casting Wikipedia as the web's good cop? Two main external factors seem to have played a key role: U.S. President Donald Trump and the coronavirus pandemic. Since Trump's election in 2016, the mainstream press expressed concerns about whether traditional notions of truth and reality-based argument. This resulted in large part from what seemed to be an official assault by the administration in the White House – both against the media itself and facts, and its offering alternative outlets for communication and "alternative facts" in their stead. The "truthiness" culture of intellectual promiscuity represented by the Presidency of George W. Bush had deteriorated into the so-called "post-truth" culture of the Trump White House. Wikipedia's procedural answers for the question of what is a fact, initially hailed as flawed due to their inherent beholdance to existing sources, could now be taken in a different light.[53]

Wikipedia had also gotten better, but its model had remained the same. What had changed was the internet and our understanding of it. Wikipedia's emphasis on neutral point of view, and the community's goal to maintain an objective description of reality, represents an increasingly striking contrast to politicians around the world whose rhetoric is not reality-based.[54] Moreover, the Wikipedia community's commitment to sourcing claims (exemplified by Wikipedia's community ban on the Daily Mail in 2017 and of Breitbart in 2018) highlighted how Wikipedia's model was seemingly more successful than the traditional media in fighting its own flaws and the rise of "fake news."[55]

2018 also saw Wikipedia lock horns with some of those considered supportive of Trump and the "post-truth" discourse, including Breitbart and even Russian media. The so-called "Philip Cross affair"[56] saw a British editor face accusation that he was in fact a front for the U.K.'s Ministry of Defense or even the American C.I.A., claims that were parroted out by Sputnik and RT. Breitbart all but declaring war on the online encyclopedia (running no less than 10 negative reports about it in as many months, including headlines like "Wikipedia Editors Paid to Protect Political, Tech, and Media Figures" and "Wikipedia Editors Post Fake News on Summary of Mueller Probe").[57] 2018 also saw the clearest example of Russian intervention in Wikipedia, with Russian agent Maria Butina being outed by the community for trying to scrub her own Wikipedia page.[58]

The shift toward more positive press treatment of Wikipedia also overlaps with a general trend toward negative coverage of for-profit technology sites. In recent years, Facebook, Google, Twitter, and YouTube have been chastised in the press for privacy violations, election hacking, and platforming hateful content. But Wikipedia has largely dodged these criticisms. Complimentary journalists have noted the site's rare position as a nonprofit in the most visited websites in the world – the only site in the global top ten that is not monetized with advertising or by collecting and selling personal information of users. Journalists have also praised Wikipedia's operating model. As Brian Feldman pointed out in a New York Magazine piece titled, "Why Wikipedia Works", the site's norms of review and monitoring by a community of editors, and deleting false information and inflammatory material, seems vastly superior to the way social media platforms like Twitter fail to moderate similarly problematic content.[59]

With the 2020 election, this process reached its zenith. While Twitter and Facebook scrambled to prevent the New York Post report about Hunter Biden from spreading through its platform, sparking yet again a debate on the limits of free speech online, the dynamic on Wikipedia was very different: Instead of censoring the link or trying to prevent its content from being disseminated, Wikipedia's editors contextualized its publication as part of a wider "conspiracy theory" relating to Biden being pushed out by Trump's proxies. By election day, Reuters, Wired, Vox and others were all praising Wikipedia for being more prepared for election disinformation than social media.

It's important to note that even during this period of relatively favorable press coverage of Wikipedia, newspapers still published highly critical articles. But the focus has been on reforming Wikipedia's governance policies rather than rejecting its underlying model of crowdsourced knowledge.[60] For example, Wikipedia received significant media attention in 2018 when Donna Strickland won a Nobel Prize in physics and, at the time of her award, did not have a Wikipedia page; an earlier entry had been deleted by an editor who found that Strickland lacked sufficient notability, despite the fact her two male co-laureates had pages for the same academic research that earned the three the prestigious award. But note how press coverage of Strickland did not dispute Wikipedia's underlying premise of community-led knowledge production. Rather press coverage was continuing the structural critique from the previous phase.

Furthermore, by this era the Wikimedia Foundation had increasingly begun speaking publicly about matters of concern to the Wikipedia community. When it came to the Strickland incident, the Wikimedia Foundation was not overly apologetic in its public statements, with Executive Director Katherine Maher writing an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times titled "Wikipedia Mirrors the World's Gender Biases, it Doesn't Cause Them".[61] Maher challenged journalists to write more stories about notable women so that volunteer Wikipedians have sufficient material to source in their attempt to fix the bias. Maher's comments, in other words, advocate further awareness of the symbiotic relationship between the media and Wikipedia.

The Strickland incident is in some ways an outlier during a time of relatively favorable press coverage of Wikipedia. How long will this honeymoon period last? One indication that the pendulum will swing back in a more-critical direction is the coverage of large technology companies using Wikipedia. The press widely covered YouTube's 2018 announcement that it was relying on Wikipedia to counteract videos promoting conspiracy theories when there had been no prior notice to the Wikimedia Foundation regarding YouTube's plans. Journalists also wrote – at times critically – about Facebook's plan to give background information from Wikipedia about publications to combat "fake news", Google's use of Wikipedia content for its knowledge panels, and how smart assistants like Siri and Alexa pull information from the site.

Prominent tech critics have questioned whether it is truly appropriate to leverage Wikipedia as the "good cop" since the site is maintained by unpaid volunteers, and tech companies are using it for commercial purposes. But from a news perspective, it might not matter so much whether it's fair or prudent for technology companies to leverage Wikipedia in this way–the appearance of partnership is enough to spur a news story. The more it seems as if Wikipedia has become aligned with Big Tech, the more likely the encyclopedia will receive similarly adverse coverage.

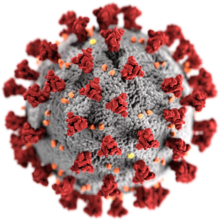

Nonetheless, coronavirus proved a pivotal moment, giving Wikipedia and its model what seems to be its biggest vindication since Nature 2005. As a key node in the online information ecosphere, and with concerns regarding Covid-19 disinformation causing the WHO to label the pandemic an "infodemic" in February 2020, vandalism on coronavirus articles was not something WP and perhaps the world could afford. Luckily, the WikiProject Medicine was prepared. "Our editing community often concentrates on breaking news events such that content rapidly develops. The recent outbreak of novel coronavirus has been no exception," Doc James told Wired magazine, in what would be the first of many stories praising Wikipedia's response to the virus due to its especially rigid sourcing policy.

The project and Doc James would turn into the face of Wikipedia's response to the pandemic – so much so that the community would even open a special article on "Wikipedia's response to the Covid-19" pandemic – a rare sign of WP's community efforts meeting their own notability guidelines. Wikipedia, as the article about its response to the pandemic both said and showed, was notably reliable due to its emphasis on neutral point of view and verification of sources. Wikipedia's Covid-19 task force had relied on the top tier of legacy media – building a list of recommended sources from popular and scientific media – and they vindicated it for their commitment to trusted institutions of authority. By the start of 2021, as the pandemic marked its one year anniversary and Wikipedia its 20th, publications across the world were praising it.

Conclusion

Over the span of nearly two decades, Wikipedia went from being heralded as the original fake news, a symbol of all that was wrong with the internet, to being the "grown up" of the web and the best medicine against the scourge of disinformation. This process was predicated on Wikipedia's epistemic model gaining social acceptance as well as the erosion of status of mainstream media and traditional knowledge sources. Comparisons to older encyclopedias have all but disappeared. More common are appeals like Maher's request following the Strickland affair that journalists aid Wikipedia in the attempt to reform by publishing more articles about women. This dynamic highlights how Wikipedia is now a fixture within our media landscape, increasingly both the source of coverage and the story itself.

Understanding the mutually affirming and dynamic between media and Wikipedia opens up a rare opportunity to engage directly with some of the issues underscoring information as well as disinformation – from critical reading of different sources, to basic epistemological debates, issues that were once considered too academic for mainstream media are now finding their place in the public discourse through coverage of Wikipedia. For example, reports about Strickland's lack of a Wikipedia article helped make accessible the feminist theory regarding knowledge being "gendered". The idea that history is his-story was highlighted in debates about Wikipedia's gender bias, with the dire lack of articles about women scientists being easily explained by the lack of historical sources regarding women. Meanwhile, reports about Wikipedia being blocked in countries such as China and Turkey have allowed for a discussion of the politics of knowledge online as well as a debate regarding the differences between Wikipedias in different languages and local biases. Detailed and critical reports like these are part of a new sub-genre of journalism that has emerged in the past years, what we term "wiki journalism": Coverage of Wikipedia as a social and political arena in its own right.[62]

Nonetheless, much more can be done – by journalists, the Wikimedia Foundation and even the Wikipedia community of volunteers. Though Wikipedia's technology purportedly offers fully transparency, public understanding of Wikipedia's processes, bureaucracy, and internal jargon is still a massive obstacle for would-be editors and journalists alike. Despite its open format, the majority of Wikipedia is edited by a fraction of its overall editors, indicating the rise of an encyclopedic elite not too dissimilar in characteristics than that of media and academia. To increase diversity in Wikipedia and serve the public interest requires journalists to go beyond "gotcha" headlines. Much of the popular coverage of Wikipedia is still lacking and is either reductive or superficial, treating Wikipedia as a unified voice and amplifying minor errors and vandalism. Many times, reports like these needlessly politicize Wikipedia. For example, after a vandal wrote that the Republican Party of California believed in "Nazism" and the error was aggregated by Alexa and Google, reports attributed blame to Wikipedia.[63]

These issues are discussed at length in our text in the Columbia Journalism Review, which urges journalists to help increase Wikipedia literacy, dedicating more coverage to the project's inner workings and policies.[1] But the media is not alone and the WMF as well as Wikipedians can also help. In recent years, the Wikimedia Foundation has taken the helpful step of hiring communications specialists and other employees to help members of the press connect with sources both at the Foundation and the larger Wikimedia movement. Yet although the Wikimedia Foundation has made press contacts much more accessible, there is still work to be done to enhance communication between Wikipedia and the media. Creating a special status for wiki journalists, for example, recognizing their users and granting them read-only status for deleted articles and censored edits – a right currently reserved for official administrators – could help reporters better understand the full context of edit wars and other content disputes.

The community must too be more open to working with media and take a much less aggressive approach to external coverage of their debates. Many times, editors are reluctant to speak to reporters and are antagonistic towards unversed users who have come to mend an error or bias they have read about in the media. In some cases, editors who speak with the press are stigmatized. Much like the interviews with editors of WikiProject Medicine's Covid-19 task force showed, working with the media can actually help highlight the important work taking place on the encyclopedia. Wikipedia editors must accept that they and their community play a much wider social role than they may perceive – a social role that places the output of their volunteer activity center stage online and also makes them part of the public debate. To help bridge the gap between public discourse and the Wikipedic one, editors need to go beyond the "just fix it yourself" mentality and help increase public oversight of Wikipedia.

As Wikipedia is fully transparent, the demand for further public oversight may seem misplaced or even anachronistic. However in much the same way we need the media to help oversee public committee hearings in town halls or national legislatures plenums, so too does the public need the media's help in participating in Wikipedia's transparency. Much like we need a strong active media to help encourage and facilitate civilian oversight of political processes, so too do we need robust media coverage to help encourage civic involvement in encyclopedic processes.

Wikipedians may not perceive themselves to be gatekeepers in the same way lawmakers or congressional aides are, but for those viewing Wikipedia from the outside, many times they do actually appear to play just such a role. Lack of public engagement in Wikipedia cannot be blamed solely on the public or its purported apathy. Wikipedians must not just allow the media to highlight problems within their community, but proactively flag issues, helping reporters sift through countless debates and find the truly important stories, instead of limiting themselves to internal forums and demanding journalists and the public fix Wikipedia themselves.

Together, journalists, the Wikimedia Foundation and the community, can help increase critical digital literacy through deeply reported coverage of Wikipedia. High-quality wiki journalism would not treat Wikipedia as a monolithic agent that speaks in one voice, but rather would seek to understand the roots of its biases and shortcomings. This will serve to highlight the politics of knowledge production instead of politicizing knowledge itself.

References

- ^ a b Stephen Harrison and Omer Benjakob, "Wikipedia is twenty. It's time to start covering it better", Columbia Journalism Review, January 14, 2021. https://www.cjr.org/opinion/wikipedia-is-twenty-its-time-to-start-covering-it-better.php

- ^ Andrew Orlowski, "Wikipedia Founder 'Shot by Friend of Siegenthaler,'" Register, December 17, 2005, https://www.theregister.co.uk/2005/12/17/jimmy_wales_shot_dead_says_wikipedia/

- ^ Marshall Poe, "The Hive," Atlantic 298, no. 2 (2006): 86, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/09/the-hive/305118/; Noam Cohen, "Conspiracy Videos? Fake News? Enter Wikipedia, the 'Good Cop' of the Internet," Washington Post, April 6, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/conspiracy-videos-fake-news-enter-wikipedia-the-good-cop-of-the-internet/2018/04/06/ad1f018a-3835-11e8-8fd2-49fe3c675a89_story.html; Noam Cohen, "Defending Wikipedia's Impolite Side," The New York Times, August 20, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/20/technology/20link.html; John Naughton, "In a Hysterical World, Wikipedia Is a Ray of Light – and That's the Truth," The Guardian, September 2, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/02/in-hysterical-world-wikipedia-ray-of-light-truth.

- ^ Alexis C. Madrigal, "Wikipedia, the Last Bastion of Shared Reality," Atlantic, August 7, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/08/jeongpedia/566897/.

- ^ Peter Meyers, "Fact-Driven? Collegial? This Site Wants You", The New York Times, September 20, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/20/technology/fact-driven-collegial-this-site-wants-you.html

- ^ a b c Judy Heim, "Free the Encyclopedias!" MIT Technology Review, September 4, 2001, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/401190/free-the-encyclopedias/

- ^ Rob Miller, "Wikipedia Founder Jimmy Wales Responds," Slashdot, July 28, 2004, https://slashdot.org/story/04/07/28/1351230/wikipedia-founder-jimmy-wales-responds. Citing Wikipedia, The New York Times Magazine chose "Populist editing" as one of 2001's big ideas: Steven Johnson, "The Year in Ideas: A to Z; Populist Editing," New York Times Magazine, December 9, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/09/magazine/the-year-in-ideas-a-to-z-populist-editing.html.

- ^ a b Leslie Walker, "Spreading Knowledge: The Wiki Way," The Washington Post, September 9, 2004, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A5430-2004Sep8.html; Wikipedia contributors, "Wikipedia: Press coverage 2003," Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:Press_coverage_2003&oldid=760053436.

- ^ Jim Giles, "Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head," Nature, December 14, 2005, https://www.nature.com/articles/438900a

- ^ Dan Goodin, "Science Journal: Wikipedia Pretty Accurate," Associated Press, December 14, 2005. The AP report was reprinted in over 112 media outlets, including Al Jazeera and The China Post. The BBC also reported about Nature's findings, writing: "Wikipedia Survives Research Test" (BBC News Online, December 15, 2005), as did Australia's The Age (Stephen Cauchi, December 15, 2005), to name a few.

- ^ John C. Dvorak, "The Wikification of Knowledge," PC Magazine, November 7, 2005, https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,1835857,00.asp; see also Jaron Lanier, "Digital Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism," Edge, May 29, 2006, https://www.edge.org/conversation/jaron_lanier-digital-maoism-the-hazards-of-the-new-online-collectivism.

- ^ Wikipedia, s.v. "Wikipedia: Wikilove from the Press," last modified January 14, 2017, Special:Diff/760052982; Wikipedia, s.v. "Wikipedia: America's Top Newspapers Use Wikipedia," accessed August 29, 2019, Special:Diff/760053107.

- ^ Wikipedia, s.v. "The Signpost," Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Signpost&oldid=913126984.

- ^ Wikipedia, s.v. "Wikipedia: Press coverage," accessed August 29, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:Press_coverage&diff=877404926&oldid=33446632.

- ^ 18. Wikipedia, s.v. "Wikipedia: Wikipedia as a Press Source," accessed August 29, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wikipedia:Wikipedia_as_a_press_source&oldid=601134577.

- ^ Katherine Q. Seelye, "Snared in the Web of a Wikipedia Liar," The New York Times, December 4, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/04/weekinreview/snared-in-the-web-of-a-wikipedia-liar.html; Jason Fry, "Wikipedia's Woes," Wall Street Journal, December 19, 2005, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB113450010488821460-LrYQrY_jrOtOK3IiwMcglEq6aiE_20061223. It was also on the front page of Asharq Al-Awsat's December 9, 2005 print edition and was even reported in Serbian: S. R., "Неслана шала са Википедије," Politika, December 16, 2005.

- ^ Allan Metcalf, "Truthiness Voted 2005 Word of the Year by American Dialect Society," American Dialect Society, January 6, 2005, 1–7.

- ^ Matthew F. Pierlott, "Truth, Truthiness, and Bullshit for the American Voter," in Stephen Colbert and Philosophy: I Am Philosophy (and So Can You!), ed. A. A. Schiller (Peru, IL: Open Court Publishing, 2009), 78.

- ^ The stunt earned Colbert (or at least a user associated with him) a lifetime ban from editing Wikipedia, but others followed suit: the Washington Post 's satirical columnist Gene Weingarten, for example, introduced errors into his own page to see how long they would stand online – a genre in its own right – see, for example, Gene Weingarten, "Wiki Watchee," Washington Post, March 11, 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/03/06/AR2007030601573.html.

- ^ Frank Ahrens, "It's on Wikipedia, So It Must Be True," Washington Post, August 6, 2006, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/2006/08/06/its-on-wikipedia-so-it-must-be-true/c3668ff7-0b66-4968-b669-56c982c2c3fd/.

- ^ David Detmer, "Philosophy in the Age of Truthiness," in Stephen Colbert and Philosophy: I Am Philosophy (and So Can You!), ed. Aaron Allen Schiller, (Peru, IL: Open Court Publishing, 2009); The Colbert Report, July 31, 2016.

- ^ Noam Cohen, "Start Writing the Eulogies for Print Encyclopedias," New York Times, March 16, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/16/weekinreview/16ncohen.html.

- ^ Simson L. Garfinkel, "Wikipedia and the Meaning of Truth," MIT Technology Review, 111, no. 6 (2008): 84–86.

- ^ George Johnson, "The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts," The New York Times, January 3, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/03/science/the-nitpicking-of-the-masses-vs-the-authority-of-the-experts.html; Paul Vallely, "The Big Question: Do We Need a More Reliable Online Encyclopedia than Wikipedia?" Independent, October 18, 2006.

- ^ Lawrence M. Sanger, "The Fate of Expertise After Wikipedia," Episteme 6, no. 1 (2009): 52–73.

- ^ Catherine Elsworth, "Wikipedia Professor Is 24-Year-Old College Dropout," 'Telegraph', March 7, 2007.

- ^ Brian Bergstein, "After Flap Over Phony Professor, Wikipedia Wants Writers to Share Real Names," Associated Press, March 7, 2007; Noam Cohen, "After False Claim, Wikipedia to Check Whether a User Has Advanced Degrees," New York Times, March 12, 2007; Noam Cohen, "Wikipedia Tries Approval System to Reduce Vandalism on Pages," New York Times, July 17, 2008.

- ^ Yuki Noguchi, "On Capitol Hill, Playing WikiPolitics," The Washington Post, February 4, 2006, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/03/AR2006020302610.htm; Nate Anderson, "Congressional Staffers Edit Boss's Bio on Wikipedia," Ars Technica, January 30, 2006 https://arstechnica.com/uncategorized/2006/01/6079-2/

- ^ Bobbie Johnson, "Conservapedia – The US Religious Right's Answer to Wikipedia," Guardian, March 2, 2007.

- ^ Jacqueline Hicks Grazette, "Wikiality in My Classroom," Washington Post, March 23, 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/03/23/AR2007032301614.html.

- ^ Wikipedia, s.v. "Reliability of Wikipedia," accessed August 29, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Reliability_of_Wikipedia&oldid=907354472.

- ^ John Schwarz, "When No Fact Goes Unchecked," New York Times, October 31,

- ^ Steve Fuller, Post-Truth: Knowledge as a Power Game (London, UK: Anthem Press, 2018), 125; John C. Dvorak, "Googlepedia: The End is Near," PC Magazine, February 17, 2005.

- ^ Katie Hafner, "Growing Wikipedia Refines Its 'Anyone Can Edit' Policy," New York Times, June 17, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/17/technology/17wiki.html.

- ^ Bobbie Johnson, "Deletionists vs. Inclusionists. Teaching People about the Wikipedia World," Guardian, August 12, 2009.

- ^ Noam Cohen, "Wikipedia May Restrict Public's Ability to Change Entries," New York Times, January 23, 2009.

- ^ Katie Hafner, "Growing Wikipedia Refines Its 'Anyone Can Edit' Policy"; Idea of the Day Series, "The Epistemology of Wikipedia," New York Times, October 23, 2008.

- ^ Terri Oda, "Trolls and Other Nuisances," New York Times, February 4, 2011; Anna North, "The Antisocial Factor," New York Times, February 2, 2011; Henry Etzkowitz and Maria Ranga, "Wikipedia: Nerd Avoidance," New York Times, February 4, 2011.

- ^ Ruediger Glott, Phillip Schmidt, and Rishab Ghoseh, "Wikipedia Survey – Overview of Results," United Nations University, March 15, 2010.

- ^ Benjamin Mako Hill and Aaron Shaw, "The Wikipedia Gender Gap Revisited: Characterizing Survey Response Bias with Propensity Score Estimation," Plos One, June 26, 2013, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.006578.

- ^ Sarah Marloff, "Feminist Edit-a-Thon Makes Wikipedia More Diverse," Austin Chronicle, March 10, 2017, https://www.austinchronicle.com/daily/news/2017-03-10/feminist-edit-a-thon-makes-wikipedia-more-diverse/.

- ^ Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, "The Geography of Fame," New York Times, March 22, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/23/opinion/sunday/the-geography-of-fame.html.

- ^ Elaine Woo, "Adrianne Wadewitz, Wikipedia Contributor, Dies at 37," The Washington Post, April 25, 2014.

- ^ Andrew McMillen, "Meet the Ultimate Wikignome," Wired, February 3, 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/02/meet-the-ultimate-wikignome/.

- ^ William Jordan, "British People Trust Wikipedia More Than the News," YouGov, August 9, 2014, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2014/08/09/more-british-people-trust-wikipedia-trust-news.

- ^ Holly Epstein Ojalvo, "How Do You Use Wikipedia? Media People Talking About How They Use It," New York Times, November 9, 2010, https://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/09/how-do-you-use-wikipedia/.

- ^ a b Noam Cohen, "When Knowledge Isn't Written, Does It Still Count?" The New York Times, August 7, 2011.

- ^ Andrew Lih, "Wikipedia Just Turned 15 Years Old. Will it Survive 15 More?" The Washington Post, January 15, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2016/01/15/wikipedia-just-turned-15-years-old-will-it-survive-15-more.

- ^ Noam Cohen, "Conspiracy Videos? Fake News? Enter Wikipedia, the 'Good Cop' of the Internet," The Washington Post, April 6, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/conspiracy-videos-fake-news-enter-wikipedia-the-good-cop-of-the-internet/2018/04/06/ad1f018a-3835-11e8-8fd2-49fe3c675a89_story.html.

- ^ Corine Ramey, "The 15 People Who Keep Wikipedia's Editors from Killing Each Other," Wall Street Journal, May 7, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/when-wikipedias-bickering-editors-go-to-war-its-supreme-court-steps-in-1525708429.

- ^ Omer Benjakob, "Verified: Wikipedia Is Our Unlikely Champion in the War of Fake News," Wired UK, July 2019, 22–23.

- ^ Madrigal, "Wikipedia, the Last Bastion of Shared Reality"; Stephen Harrison, "Happy 18th Birthday, Wikipedia. Let's Celebrate the Internet's Good Grown-up," Washington Post, January 14, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/happy-18th-birthday-wikipedia-lets-celebrate-the-internets-good-grown-up/2019/01/14/e4d854cc-1837-11e9-9ebf-c5fed1b7a081_story.html.

- ^ Omer Benjakob, "Is the Sky Blue? How Wikipedia Is Fighting for Facts by Redefining the Truth," Haaretz, December 15, 2017, https://www.haaretz.com/science-and-health/.premium.MAGAZINE-how-wikipedia-is-fighting-for-facts-by-redefining-the-truth-1.5628749.

- ^ Madrigal, "Wikipedia, the Last Bastion of Shared Reality."

- ^ Stephen Amstrong, "Inside Wikipedia's Volunteer-run Battle Against Fake News," Wired, August 21, 2018, https://www.wired.co.uk/article/fake-news-wikipedia-arbitration-committee.

- ^ Benjakob, Omer (May 17, 2018). "The Witch Hunt Against a 'Pro-Israel' Wikipedia Editor". 'Haaretz.

- ^ Omer Benjakob, "Breitbart Declares War on Wikipedia as Encyclopedia Gets Drafted into Facebook's 'Fake News' Battle," Haaretz, April 24, 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-breitbart-declares-war-on-wikipedia-in-facebook-s-fight-against-fake-news-1.5991915.

- ^ Lachlan Markay and Dean Sterling Jones, "Who Whitewashed the Wiki of Alleged Russian Spy Maria Butina?" Daily Beast, July 24, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/who-whitewashed-the-wiki-of-alleged-russian-spy-maria-butina/.

- ^ Brian Feldman, "Why Wikipedia Works," New York Magazine, March 16, 2018, http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/03/why-wikipedia-works.html.

- ^ Martin Dittus and Mark Graham, "To Reduce Inequality, Wikipedia Should Consider Paying Editors," Wired UK, September 11, 2018, https://www.wired.co.uk/article/wikipedia-inequality-pay-editors.

- ^ Katherine Maher, "Wikipedia Mirrors the World's Gender Biases, It Doesn't Cause Them," Los Angeles Times, October 18, 2018, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-maher-wikipedia-gender-bias-20181018-story.html.

- ^ Brian Feldman, "Why Wikipedia Works," New York Magazine, March 16, 2018, http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/03/why-wikipedia-works.html.

- ^ "Google Blames Wikipedia for Linking California GOP to Nazism," Associated Press, June 1, 2018.

Wikipedia's war against scientific disinformation

- Mary Mark Ockerbloom was a Wikipedian-in-residence at the Science History Institute from 2013 to 2020.

The playbook for undermining scientific expertise was created in the 1920s. Perhaps surprisingly, its creators were scientists. Wikipedia is one battleground in the hundred years' war against scientific disinformation. The tactics of scientific disinformation that were developed then are still used today. We need to be aware of these tactics so that we can counter them; we also need more scientifically-savvy allies to help us get it right.

The practice of scientific disinformation

On December 3, 1921, Thomas Midgley Jr. and Charles Kettering, scientists at General Motors, discovered that adding tetraethyllead (TEL) to gasoline improved a car's performance.[1] As patent holders of the new technology who held senior positions in the companies producing and marketing TEL, Kettering and Midgely had everything to gain by promoting TEL's use rather than developing other non-patentable alternatives.[1][2]

TEL contains lead: an odorless, colorless, tasteless, poisonous element. Once present in a person, lead does not degrade, it accumulates.[3][4] Kettering and Midgley were warned of the dangers of lead and TEL by other scientists. Erik Krause of the Institute of Technology, Potsdam, Germany had studied TEL extensively, and described it as "a creeping and malicious poison".[2] Internal confidential reports document that the companies involved knew TEL was "extremely hazardous",[1] while their safety precautions were "grossly inadequate".[1]

By 1923, cases of violent madness and death were being reported among workers at TEL plants. At least 17 persons died, and hundreds more suffered neurological damage.[5][6] Postmortems confirmed the cause as tetraethyllead.[7] Coworkers referred to the fumes they breathed as "loony gas" and to a building they worked in as the "House of Butterflies", because workers had hallucinations of insects.[6]

The newspapers, the public, and the government began to take notice.[5] Midgley himself was treated for lead poisoning. Despite this, he protested that TEL was perfectly safe, even washing his hands in it in front of reporters on October 30, 1924,[1][3] the same day the New York City Board of Health banned the sale of TEL-enhanced gasoline.[1][3]

As concerns about TEL grew, Kettering took protective measures for the company, but not its workers. He hired Robert A. Kehoe, a 1920 medical school graduate, as an in-house "medical expert" whose job was to prove that leaded gasoline did not harm humans. An early study is illustrative of the methodological problems in his work. In that study he reported that workers handling TEL had levels of exposure no higher than a control group, which was composed of workers at the same plant. He suggested their levels of lead were "normal", equating normal and harmless.[8]

Alice Hamilton was among those who criticized Kehoe's research. A pioneer in industrial toxicology and occupational health, Hamilton was America's leading authority on lead poisoning, with decades of experience in public health research and policy-making.[9] On May 20, 1925, Hamilton and other public health advocates from Harvard, Yale and Columbia faced off against Kettering, at a conference called by the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service to consider the use of lead in gasoline. Would lead in gasoline be released into the air when the fuel was burned, putting the general public at risk? Hamilton warned that lead posed environmental as well as occupational dangers. "You may control conditions within a factory, but how are you going to control the whole country?"[10] Kettering argued that TEL was the only way to improve gasoline, and asserted that no one had proved that leaded gasoline was harmful.[1][10]

The conference ended with the formation of a committee to further investigate the possible effects of leaded gasoline. The committee could have taken responsibility for further independent research, but public health advocates lacked funding, and the government wasn't willing to provide it. In a classic case of setting the fox to watch the henhouse, the commission chose to rely on industry to monitor itself, ignoring the inherent conflict of interest. Not surprisingly, Robert Kehoe reported that the industry-funded research showed "no evidence of immediate danger to the public health."[10][11]

Hamilton reportedly told Kettering to his face that he was "nothing but a murderer".[2][1] Kettering formed the Kettering Foundation for public policy-related research. Kettering and Midgley developed Freon, which eventually became another environmentally disastrous product.[2] Kehoe became the gasoline industry's chief spokesperson, largely controlling the next fifty years of scientific and public narrative around leaded gasoline.[11][8]

Risk, responsibility and the undermining of science

Public health advocates and corporate representatives took different approaches to risk and responsibility in the debate over leaded gasoline. Public health followed a precautionary principle, arguing that unless scientists could demonstrate that something was safe, it should not be used. The Kehoe paradigm laid the burden of proof on the challenger. Rather than demonstrating that their product was safe, they demanded that critics prove it was harmful. But Kehoe's rule is logically flawed – absence of evidence of risk does not imply evidence of the absence of risk. Regardless, the Kehoe paradigm became extremely influential in the United States.[11][8][12]

This not only set scientist against scientist, it made the undermining of science tactically useful. Experimental research is a method of testing ideas and assessing the likelihood that they are correct based on observable data. By its very nature, the results of a scientific study do not provide a 100% yes-or-no answer. Disinformation exploits this lack of absolute certainty by implying that uncertainty means doubt. If evidence is presented to challenge a position, it is suggested that the proof is not sufficiently compelling, that doubt still remains, that more research must be done, and that no responsibility need be taken in the meantime. By repeatedly raising the issue of doubt, companies and scientists use "cascading uncertainty" to manipulate public opinion and protect their own interests.[13][14][15][12]

In the 1960s geochemist Clair Patterson developed sophisticated monitoring equipment and methods to measure the history of the earth's chemical composition. Initially uninterested in lead, his research provided compelling evidence of its extraordinary increase in the planet's recent history. Patterson broke the industry's leaded gasoline narrative. The industry spent almost 25 years trying to discredit him and his work through professional, personal, and public attacks. Nonetheless Patterson did what Kettering and Kehoe had challenged public health officials to do in 1925 – demonstrate the impact of TEL from gasoline.[11][8][12]

By then, lead contamination from gasoline (and from paint) was found worldwide, not just in North America. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers lead to be one of the top ten chemicals posing a major public health risk, with immense personal, social and economic costs. One of the "key facts" they state is "There is no level of exposure to lead that is known to be without harmful effects."[4]

Kettering's playbook has been replicated repeatedly. Companies and their researchers have argued that smoking, CFCs, opioids, vaping, fossil fuels and climate change (to name only a few) aren't really dangers; that concerns about public safety and environmental damage have not been sufficiently proven and so do not require action; and that raising a shadow of doubt is enough to challenge widespread scientific consensus. I strongly recommend reading Merchants of Doubt (Oreskes & Conway, 2010)[13] and Doubt Is Their Product (2008)[14] and The Triumph of Doubt (2020) by David Michaels.[15]

At its most extreme, we face an attitude that assumes scientific issues are simply matters of opinion and belief, independent of underlying scientific evidence and informed consensus. The dangers of this are apparent: We are in the midst of a pandemic that some refuse to believe exists. Anti-mask and anti-vaccination propaganda are recent areas of scientific disinformation, putting us all at risk.[16]

Defeating scientific disinformation on Wikipedia