Dude, Where's My Donations? Wikimedia Foundation announces another million in grants for non-Wikimedia-related projects

Wikimedia Foundation gives away about $1 million in grants to counter racial bias and discrimination

In 2021, the Wikimedia Foundation announced the first grants of a "Knowledge Equity Fund" created in June of the previous year. This involved about a million dollars of WMF funds being given, in the form of grants, to a number of external charitable and advocacy organizations.

This proved controversial; as we covered last October, a "somewhat-viral Twitter thread" questioned the relevance of these organizations to Wikimedia projects and values, and while some of the controversy was certainly political in nature, many of the grant recipients seemed unrelated to Wikimedia projects, prompting further discussion on mailing lists. One concern was the lack of community input into the process that led to the fund's creation. Another was the use of money which was generally solicited on the grounds of being necessary to fund Wikimedia projects, meaning that many donors likely did not know or intend for their funds to be given to unrelated organizations. Two of the grant recipients from the first round seem to have not shared financial reports detailing how the money was spent.

The Wikimedia Foundation has announced a second round of grantees this month, saying in its announcement:

Equity – more specifically, knowledge equity – underpins our movement's vision of a world in which every human can share in the sum of all knowledge. It encourages us to consider the knowledge and communities that have been left out of the historical record, both intentionally and unintentionally. This is an important pillar of the Wikimedia movement’s strategic direction, our forward-looking approach to prepare for the Wikimedia of 2030.

There can be many reasons behind these gaps in knowledge, derived from systemic social, political and technical challenges that prevent all people from being able to access and contribute to free knowledge projects like Wikimedia equally. In 2021, the Wikimedia Foundation launched the Knowledge Equity Fund specifically to address gaps in the Wikimedia movement's vision of free knowledge caused by racial bias and discrimination, that have prevented populations around the world from participating equally. The fund is a part of the Wikimedia Foundation’s Annual Plan for the 2023-24 fiscal year to support knowledge equity by supporting regional and thematic strategies, and helping close knowledge gaps. Building on learnings from its first round of grants, today the Equity Fund is welcoming its second round of grantees.

This second round includes seven grantees that span four regions, including the Fund's first-ever grantees in Asia. This diverse group of grantees was chosen from an initial pool of 42 nominations, which were received from across the Wikimedia movement through an open survey in 2022 and 2023. Each grantee aligns with one of Fund's five focus areas, identified to address persistent structural barriers that prevent equitable access and participation in open knowledge. They are also recognized nonprofits with a proven track record of impact in their region. The Knowledge Equity Fund was initially conceived in response to global demands for racial equity, and the global reach of these new grantees is testament to and in recognition of the systemic impact of racial inequity in affecting participation in knowledge across the world.

The grants announced are as follows:

$290,000 USD to Black Cultural Archives, United Kingdom

Black Cultural Archives is a Black-led archive and heritage center that preserves and gives access to the histories of African and Caribbean people in the UK. Their goals with this grant for the coming year include increasing research into their collections, as well as increasing the breadth of their collections for research.

$200,000 USD to Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara, Indonesia

The Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara, or the Alliance of the Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN for short), is a non-profit organization based in Indonesia that works on human rights and advocacy issues for indigenous people.

$160,000 USD to Criola, Brazil

Criola is a civil society organization, based in Rio de Janeiro, dedicated to advocating for the rights of Black women in Brazilian society. They prioritize knowledge production, research, and skills development as part of their work. They are also part of a national and international network of human rights, justice and advocacy organization focused on promoting racial equity.

$100,000 USD to Data for Black Lives, United States

Data for Black Lives is a movement of activists, organizers, and scientists committed to the mission of using data to create concrete and measurable change in the lives of Black people. They will use the grant in part to launch a Movement Scientists Fellowship matching racial justice leaders with machine learning research engineers to develop data-based machine learning applications to drive change in the areas of climate, genetics, and economic justice.

$75,000 USD to Create Caribbean Research Institute, Commonwealth of Dominica

Create Caribbean Research Institute is the first digital humanities center in the Caribbean. The grant will be used to expand Create Caribbean’s Create and Code technology education program to enable children ages 5-16 to develop information and digital literacy as well as coding skills.

$70,000 USD to Filipino American National Historical Society, United States

The Filipino American National Historical Society, or FANHS, has a mission to gather, document and share Filipino American history through its 42 community based chapters. The grant will support continuing and growing FANHS’ scholarship and advocacy on accurate historical representations of Filipino Americans and counter distorted and effaced ethnic history.

$50,000 USD to Project Multatuli, Indonesia

Project Multatuli is an organization dedicated to non-profit journalism, especially for underreported topics, ranging from indigenous people to marginalized issues. Their goal is to produce data-based, deeply researched news stories to promote inclusive journalism and amplify the voices of marginalized communities.

For further background on the grantees, see the Wikimedia announcement. – AK, JG

Jimbo promises improvements for Wikimedia Endowment's lackluster transparency

On the subject of financial transparency regarding the Wikimedia Endowment: here is what the minutes of the January 2022 board meeting had to say about it. Not exactly a wealth of detail, but we do at least get a financial summary:

8) Fundraising update

- Overview, lead by Caitlin Virtue

- Review of Fundraising Report, lead by Amy Parker

- Summary: As of December 31, 2021, the Endowment held $105.4 million. There is currently $99.33 million in the investment account and $6.07 million in cash. An additional $8 million raised in December will be transferred to the Endowment in January 2022.

This summary was the last time the Endowment Board meeting minutes contained a dollar figure for the Endowment's total value (cash plus investments). Requests for an updated figure in February remained unanswered in July.

A couple of weeks ago, the Wikimedia Foundation's Jayde Antonio posted the approved minutes for the January 19, 2023 Endowment Board meeting to the its page on Meta. Noticeable here is the lack of any substantial new information – apart from noting the approval of the Endowment grants which were announced publicly back in April, they essentially just repeat the boilerplate meeting agenda posted months ago.

For example, the meeting's agenda (posted in February 2023) contained the following item:

6:25 - 6:55 pm UTC: Fundraising Update (Board Chair, Jimmy Wales and Endowment Director, Amy Parker)

- FY22-23 year to date update

- Campaign strategy

The minutes approved by the Endowment's board, led by Jimbo Wales, repeated the same point almost verbatim when they were added in July:

Fundraising Update (Amy Parker)

- FY22-23 year to date update

- Presentation of campaign strategy

Following a query on his user talk page about the Endowment's apparent secrecy, Jimbo appeared to criticize the minutes approved by him and his board:

At the meeting we discussed, to universal agreement, that we should publish more information and more often [...] the discussion about publishing more information and more often came about in no small part because the January minutes were something that I felt were not good enough in terms of being open and informative. (A financial report is forthccoming – I haven't seen it yet – but delayed because the relevant person creating it has taken a bit of family leave.)

This is a strange comment, as it would seem entirely within the power of the board to determine what information the minutes of its own meetings should contain. He later clarified: "The minutes of the previous board meetings are not written in realtime in the board meeting. They are a legal document prepared in advance and reviewed by the legal team and staff."

Following that discussion, however, Wales did provide a more meaningful update on Meta-Wiki:

In official business, the Board moved to hire KPMG as our independent auditor for the new entity, approved a spending policy for the Endowment, approved an operational budget of $2.09 million, and approved a grantmaking budget of $2.91 million for FY 2023-24. We also set the target of $11.5 million in revenue between fundraising and investment income this fiscal year. We ended the last fiscal year with $118 million in the Wikimedia Endowment and are projecting to grow the corpus by approximately $6.5 million depending on market performance and after expenses.

How much of this $118 million is held by the Tides Foundation, and how much by the new 501(c)(3) organization, is unknown. The Wikimedia Foundation has been keen to emphasize that the Endowment is now a transparent 501(c)(3) non-profit, fulfilling a promise first made in 2017, but the Endowment website itself continues to say:

The Endowment has been established, with an initial contribution by Wikimedia Foundation, as a Collective Action Fund at Tides Foundation (Tax ID# 51-0198509).

Jimmy Wales also uploaded a document to Meta-Wiki titled "Wikimedia Endowment 2023-24 Plan". This provides information on fundraising goals, an operational timeline, and the Endowment's budget for 2023–2024. It mentions $1.8 million in annual expenses in the most recent financial year (similar to the figure mentioned in the minutes for the July 2022 board meeting), including $400,000 for unspecified professional services. It envisages the Endowment standing at $130.4 million by the end of the 2023–2024 fiscal year.

Even with the information now provided, the Wikimedia Endowment has never published a statement detailing its revenue and expenses for any year of its existence. Its actual receipts and spending from 2016 to the present day, including the fees paid to Tides, are completely opaque. The Wikimedia Endowment, the Wikimedia movement's richest affiliate, remains some way away from delivering the level of transparency ordinarily expected of Wikimedia affiliates.

See also:

– AK

Wikifunctions goes live

The Wikimedia Foundation has announced that after three years of development, its Wikifunctions project is slowly beginning to roll out.

Wikifunctions, the newest Wikimedia project, is a new space to collaboratively create and maintain a library of functions. You can think of these functions like recipes for a meal—they take inputs and produce an output (a reliable answer). You might have experienced something similar when using a search engine to find the distance between two locations, the volume of an object, converting two units, and more.

The announcement describes Wikifunctions as "a core component of the larger" Abstract Wikipedia, a project designed to have volunteers writing simple Wikipedia articles in code that can then be translated into human languages. Both projects are spearheaded by Denny Vrandečić, the former project lead of Wikidata and a past Google employee. You can learn more about how Wikifunctions works in this short video on Commons and YouTube.

A technical evaluation published in December 2022 had criticized this "decision to make Abstract Wikipedia depend on Wikifunctions, a new programming language and runtime environment, invented by the Abstract Wikipedia team, with design goals that exceed the scope of Abstract Wikipedia itself, and architectural issues that are incompatible with the standards of correctness, performance, and usability that Abstract Wikipedia requires." However, Vrandečić's team disputed such criticisms and rejected the evaluation's recommendations, which had included decoupling Wikifunctions from Abstract Wikipedia, and having it based on the existing Lua programming language that is already integrated into MediaWiki and widely used by Wikipedia editors (see detailed Signpost coverage). – AK, H

Wikimania Singapore

Wikimania 2023 is taking place in Singapore this week, from 16 to 19 August, with some workshop, hackathon and pre-conference activities happening on 15 August. Event partners include UNESCO, Google, Creative Commons and Mozilla as well as a number of Singaporean partners like NETS and the National Library Board.

While this year is the first time since 2019 that the Wikimedia movement's annual conference is happening as an in-person event again, it is also open to remote participation. The full schedule can be found here.

The Signpost wishes all those who travel to Wikimania safe journey and a great conference!

Brief notes

- Annual reports: Tyap Wikimedians User Group; Wikimedia Finlands (Financial report); Wiki Cemeteries User Group.

- New administrators: The Signpost welcomes the English Wikipedia's newest administrator, User:Pppery. Pppery, a prolific technical editor, faced limited opposition during his RfA due mainly to a perceived lack of content creation, finishing with 73% support, near the upper end of the discretionary range. Bureaucrats agreed unanimously in the 'crat chat that there was consensus to promote. – Sdkb

- Articles for Improvement: This week's Article for Improvement (beginning 14 August) is Miss. It will be followed the week after by Physiology. Please be bold in helping improve these articles!

An accusation of bias from Brazil, a lawsuit from Portugal, plagiarism from Florida

Glenn Greenwald on Wikipedia's neutrality

Glenn Greenwald is one of the three journalists who broke the Edward Snowden story that won The Guardian a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 2014. Living as an expat in Brazil, he has been a vociferous critic of many things over the years, including both major United States political parties, and was one of the founders of The Intercept – a publication he left in 2020, saying that its editors had demanded he redact an article about media coverage of that goddamn Hunter Biden laptop thing.

In a video on YouTube – an excerpt from a much longer (almost two hours long), paywalled episode Greenwald has published on Rumble (transcript here, also mostly paywalled) – Greenwald talks with Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger, and says that his Wikipedia biography changed in surprising ways after he angered the libs:

I really started noticing things going completely awry when I really started to have what was perceived to be a breach with the political faction with which I had long been associated, at least in the public mind, which was kind of American liberalism [...] I kind of became an opponent of the liberal establishment and its orthodoxies and tactics and what I began to notice was that things that were on my Wikipedia page for over a decade with no change things about events in my life from 10, 20, 30 years ago that had never been altered, suddenly every sentence became a war to try and insert negative insinuations or all kinds of innuendo, all sorts of incredibly tendentious characteristics and descriptions about my work that were designed to be negative to the point where my entire page became an ideological war because of the fact that my perceived political place in the ecosystem had shifted.

It is certainly true that his biography in late 2015 was by and large celebratory, and today is considerably less so. The early life and career sections preceding the discussion of what many people would consider Greenwald's finest hour and his main claim to fame, the Snowden story, today run to a huge 1,720 words (versus 1,043 words back then).

Here are a couple of the passages that have been expanded:

(2015:) While a senior in high school, at 17, he ran unsuccessfully for the city council.[37]

Boy, what a go-getter! The 2023 version reads very differently:

(2023:) Inspired by his grandfather's time on the then-Lauderdale Lakes City Council, Greenwald, still in high school, decided to run at the age of 17 for an at-large seat on the council in the 1985 elections.[17] He was unsuccessful, coming in fourth place in the race with only 7% of the total vote that election.[18] In 1991, Greenwald ran again for the at-large seat on the council at age 23, coming in third place but losing once again with less than half of the total votes of his other two opponents.[18][19] After two losses during his campaigns for the city council, Greenwald stopped running for political office and instead focused on law school.[13]

Sure, it is a neutrally phrased expansion from reliable sources, but doesn't he sound like kind of an asswipe?

Here is another section that has been expanded:

(2015:) Greenwald practiced law in the Litigation Department at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz (1994–1995); in 1996 he co-founded his own litigation firm, called Greenwald Christoph & Holland (later renamed Greenwald Christoph PC), where he litigated cases concerning issues of U.S. constitutional law and civil rights.[8][31] One of his higher-profile cases was the representation of white supremacist Matthew F. Hale.[38] About his work in First Amendment speech cases, Greenwald told Rolling Stone, "to me, it's a heroic attribute to be so committed to a principle that you apply it not when it's easy...not when it supports your position, not when it protects people you like, but when it defends and protects people that you hate".[39]

(2023:) Greenwald practiced law in the litigation department at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz from 1994 to 1995. In 1996, he co-founded his own litigation firm, Greenwald Christoph & Holland (later renamed Greenwald Christoph PC), where he litigated cases concerning issues of U.S. constitutional law and civil rights.[11][12] He worked pro bono much of the time, and his cases included representing white supremacist Matthew Hale in Illinois, who, Greenwald believed, was wrongly imprisoned,[21] and the neo-Nazi National Alliance.[22]

About his work in First Amendment speech cases, Greenwald told Rolling Stone magazine in 2013, "to me, it's a heroic attribute to be so committed to a principle that you apply it not when it's easy ... not when it supports your position, not when it protects people you like, but when it defends and protects people that you hate".[23]

Another difference between the 2015 and 2023 versions is that the 2023 version contains a prominent, 400-word paragraph titled "Israel and accusations of antisemitism". Even though this paragraph is based on sources dating as far back as 2012, the word "antisemitism" did not occur in the 2015 article, which merely noted that –

(2015:) Greenwald is critical of Israel's foreign policy and influence on U.S. politics,[102] a stance for which he has in turn been the subject of criticism.[103][104]

Patriotic hero, or despicable scum?

The answer is really a matter of opinion. Greenwald's own writing has shifted tone in the last few years. So has the tone of much journalistic output. While it's clear the article in 2023 takes a few jabs — and maybe unfairly so — who's to say that the article in 2015 wasn't unfairly pulling punches? Maybe this is bias and maybe it isn't. Ultimately, Wikipedia processes derive their just powers from the consensus of the governed, et cetera, which means "who the hell knows?"

Certainly, the distinguished editors of the Signpost (hopefully) have better things to do than get dragged into spittle-flecked noticeboard threads about American Punchfest 2, so not us.

The Australian's Adam Creighton picks up on Greenwald's video and adds a few Wikipedia criticisms of his own that are again likely to inflame the noggin and stir the passions. – AK, AC, JG

Portuguese lawsuit

Techdirt and the Wikimedia Foundation report on a lawsuit in Portugal brought by Caesar DePaço. As the Wikimedia Foundation's article says:

The case started in August 2021 with a complaint that de Paço was upset about the Portuguese and English language versions of the articles about him. These contain information about his right-wing political affiliations and past criminal accusations, topics that had been reported in reliable sources as publicly relevant. The lawsuit went to court in Portugal, and the Foundation won the preliminary case. Like most courts around the world, the lower court’s decision protected the ability of volunteers to research and write about notable topics, including biographies. However, the case took a strange turn on de Paço’s appeal. We are filing a series of appeals of our own in Portugal to protect the safety of users who contribute accurate and well-sourced information on important topics to Wikipedia. In our 5 July filing, we asked the Portuguese appellate court to refer several important legal questions to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). However, the Portuguese court ruled against us on 13 July, and demanded that the Foundation turn over personal data about multiple users who worked on the article.

Techdirt's Tim Cushing defends Wikipedia in his piece:

Whatever anyone's concerns are about the ability of Wikipedia to deliver facts, it should never be assumed false information will be given a tacit blessing to remain online. The normal moderation issues are present at Wikipedia, which cannot possibly afford (like any other major internet player) to physically backstop all content creation.

But that doesn’t mean Wikipedia doesn’t care whether or not pages are factual. It does. And that’s why Wikipedia (or its founding entity, Wikimedia) has rarely been sued (and never successfully) over information posted to the site by its users.

However, Cushing's statement that the Wikimedia Foundation has never been successfully sued is incorrect. There have been European court decisions ordering the Wikimedia Foundation to remove content from Wikipedia – examples from the German Wikipedia include the Kessler cases (court documents 1 and 2) and the Waibel case (see also English-language case summary by the plaintiff's lawyers). – AK

In brief

- "Egregious" plagiarism: Salon writes that Anthony Sabatini's college thesis on Friedrich Nietzsche was full of "egregious" plagiarism of Wikipedia and other online sources. Perhaps he can get out of it by "writing" an article on academic fraud.

- Creationism isn't taken seriously on Wikipedia, says creationist, invokes co-founder: David Klinghoffer writing in the Discovery Institute blog claims that Larry Sanger supports Intelligent Design, and fought to make Wikipedia handle it more favourably. Larry Sanger has described himself on Wikipedia as "an agnostic who believes intelligent design to be completely wrong", but is indeed a longstanding critic of the way Wikipedia implements its neutral point of view policy, especially when it comes to presenting fringe theories as untrue (he feels they should be presented as equally valid, then let the reader decide, as per previous link and pretty much all his writing on the subject).

- Wikipedia turns man into racehorse, and back again: The biography page of British TV personality Les Dennis was vandalized around 9 August to indicate the celebrity was half horse or some such, and people noticed, including the Bristol Post. [1]

- Sensitive topics: The Guardian reports on topics of particular PR interest to the United Arab Emirates, whose climate change-related Wikipedia editing has been in the news of late (see previous Signpost coverage).

2023 Good Article Nomination drive is underway: get your barnstars here!

The Good Article process relies on reviewers, who assess whether nominations fit the criteria and help improve articles to the point they can become GAs. One regular initiative is backlog drives, a concentrated month-long effort to review as many articles as possible with barnstar rewards. Backlog drives have a real impact on the process -- for example, the January 2022 drive took GAN from 462 unreviewed nominations to 165, a reduction of 64.3%! Despite the success of the practice, no drives ran for over a year after the end of the June 2022 drive, and various changes to the GA process in the interim resulted in a spiralling backlog.

The August 2023 drive is now nearly two weeks in, and so far has been a great success! As of press time, we're at a 43.7% reduction and not yet slowing down. The backlog has gone from an almost unheard of 638 down to 359, and every eligible nomination that had gone without a reviewer for 180 days or more at the start of the drive is now reviewed.

Nonetheless, there are still plenty of articles to review, and signups are still open! Anyone interested in participating in the drive is encouraged to do so, and any review started at the beginning of August or later can be submitted for points. We've been heartened to see the enthusiasm for the drive and the work that's been done to solve the backlog, and we'd appreciate any more help possible. If you've ever benefitted from the existence of the Good Article process, why not give back?

Thirteen years later, why are most administrators still from 2005?

Thirteen years ago today, I wrote a Signpost article, which among other things lamented that a Wikigeneration gap was emerging. At that time, over 90% of our administrators had made their first edit more than three and a half years earlier.

Things have not gotten better over time. Actually, they have gotten worse! In 2010, 90% of admins had made their first edit more than three and a half years prior. In 2023, 99% of our admins made their first edits over four and a half years ago. As for that 90% threshold I used in 2010? Over 90% of current admins made their first edit before I wrote that article. As an editor who started in 2007, I'm still relatively new compared to most of our admins — a majority of whom joined the project in 2005 or earlier.

In thirteen years, the Wikigeneration gap has widened by twelve years.

| Year | Year that Aug 2010 admins started editing (as of 2010) |

Year that Aug 2023 admins started editing (as of 2023) |

Ratio, 2023 vs. 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 32 | 8 | 25% |

| 2002 | 109 | 38 | 35% |

| 2003 | 223 | 75 | 34% |

| 2004 | 404 | 168 | 42% |

| 2005 | 481 | 198 | 41% |

| 2006 | 326 | 184 | 56% |

| 2007 | 115 | 63 | 55% |

| 2008 | 43 | 43 | 100% |

| 2009 | 13 | 27 | 208% |

| 2010 | 0 | 14 | |

| 2011 | 12 | ||

| 2012 | 10 | ||

| 2013 | 6 | ||

| 2014 | 5 | ||

| 2015 | 9 | ||

| 2016 | 2 | ||

| 2017 | 5 | ||

| 2018 | 7 | ||

| 2019 | 4 | ||

| 2020 | 2 | ||

| 2021 | 2 | ||

| 2022 | 0 | ||

| 2023 | 0 | ||

| Total | 1746 |

881 |

This is a comparison of the admins of August 2010 versus the admins of August 2023, by the year they created their account on the English Wikipedia. Note that in some cases (many in more recent years) it won't be the same editors — this is when people started editing, not when they became admins. The 2010–11 study is here.

Admins by year started editing. As at Aug 2023

I can understand why we don't yet have any admins who started editing in 2022 or 2023: few candidates now succeed without two years' experience in the community, and candidates with only one year of experience are very rare indeed. But I'm surprised at how few admins we have who joined the community in the entire decade of the 2010s, and especially with the class of 2016. Why do we only have two admins who started editing in that year?

This study looks at admins not by when they became admins, but by when they joined the community. If this inspires someone to go off and analyse things by when people became admins, then I'd be interested to see the result; I think both approaches are potentially interesting (to be honest, I suspect that I used account creation date for the 2010 study because it was easier for me to get that data). As for the 2023 study, there is an advantage in repeating the same analysis (on the same benchmark) thirteen years later. But the results are starker, as many of the three hundred new admins we've had since I published that article thirteen years ago were already editing at that point.

On the flip side, I doubt if anyone imagined thirteen years ago that so many of us would still be adminning on this site thirteen years later. My hope is that we can persuade some Wikipedians who joined the community in the 2010s to become admins; I'm sure there are many of you who would pass easily. But given the fact that we have kept Wikipedia supplied with admins through the last decade, less by recruiting more of them than by retaining the ones we had, I'm confident that if Wikipedia is still here in 2036, many of our current admins will still be around.

I just hope they are outnumbered by new recruits.

How to find images for your articles, check their copyright, upload them, and restore them

This was originally written for the August issue of The Bugle, the Military History WikiProject's newsletter.

How to find images for your articles – and what not to do. |

So, I've been working primarily with images on Wikipedia for, like, a decade now. I have a number of sites I regularly use to find images (and, no doubt, a lot of sites I've used before and forgot about). I know how to figure out what copyright tag to use, I know what good procedure is for documenting an image, and I can give some advice on how to modify an image. And I know how to avoid common pitfalls: To wit, upload the original, unmodified image first, then upload your modified version, and provide links between them, so that A. everyone knows what changes were made, and B. if the site you got the image from goes down, we can still find the original image. But more on that later. So much more.

This started out as a fairly simple article and then kept growing and growing; as such I kind of worry I've ended up with a five-article series that all got published at once. It starts off with a list of sources for images, goes into a description of some techniques to get around attempts to keep you from being able to download images, then explains how to judge if an image is out of copyright, explains how to work out what information to include when uploading an image, then the last two sections were my original plan for the article; a description of common pitfalls that come about when people upload images without documenting changes they've made to them. And then I ended by discussing how to choose images for image restoration. That's a lot. (At least I saved the guide to the actual process of restoring images for later. Sort of.) I'd imagine different parts of this article are going to be useful for different people, so feel free to skip around.

Places to get images |

Before we begin, I should probably note that the archives I use are best for events in Europe and North America after about 1700, Australia and New Zealand after 1800, and then a random selection of earlier periods and the rest of the world depending what's in the archives, though Google Art Project does do something to extend that. But it's just a lot easier to research if you at least know the alphabet in question, so there's going to be some major gaps, since, for example, the best sources for Japanese culture and history are likely to be in Japanese, and I can't write a proper search term in kanji, or even be guaranteed to find the button to get to the search box in Japanese.

Luckily, the legacy of colonialism means that large amounts of treasures of the rest of the world have been dragged off to Europe and America. How convenient! Also luckily, I'm writing for a readership who I think I can expect to understand sarcasm.

Sources in The United States of America

America seems particularly good with releasing content; British sources, for example, tend to be locked down, and Canadian sources are generally unwilling to release more than a thumbnail-sized image. So it's often worth checking these sources first.

- The Library of Congress

- Fairly easy to use, though you might need to play with the options on the left after a search, for example, limiting it to images. Good variety, including a lot of random things, like Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky's early colour photographs of Russia and a collection of WWI and WWII propaganda posters. Weird quirk of the site: Always grab the TIFF version given a choice; the JPEGs tend to be much, much smaller. For larger TIFFs, note that this is one of the sites Commons allows direct uploads from if you grab the link to the TIFF (just choose the "Source URL" button from the basic upload form.)

- The Smithsonian Institution

- One of the more convenient ones to use: Just click on the magnifying glass at the top right, put in your search, and click on Collection Images. There are technically some that don't come up in that search, though I really don't know why.

- Naval History and Heritage Command

- The U.S. Navy has a shockingly good site; one wishes that the other service branches did half so good of work on this. Incredible resource.

- The Metropolitan Museum

- Has a lot more things than you'd think it would. For example, a great selection of Timothy H. O'Sullivan's work, as well as other early photographers. Well worth a check.

- National Archives and Records Administration

- Loads of unique content, limited by poor searching and spotty digitisation. Also loads of errors.

- Folger Shakespeare Library

- One of those sources that's hyper-focused, but within that hyper-focus really broad. For example, this 1650 reconstruction of the Temple of Solomon. If there's a chance it's in scope, it's worth checking.

- Digital Public Library of America (DPLA)

- This is kind of your catch-all for American sources not found above. The interface is a little awkward, but it covers a lot of American museums and libraries. Click through to the library, and note that the image shown may be one of several, and that some of the images NOT shown on DPLA searches will actually display if you click through. Weird quirk of the site: A lot of images that don't display on DPLA will show fine if you click through to the original organisation.

There's a lot of sources indexed in DPLA that I actually really like, such as the Minneapolis Institute of Art, but since they are indexed in DPLA, it's probably unnecessary to list them separately.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom tends to be quite locked down, but there are exceptions. I'm sure there's other good ones, but these are ones I find generally very good:

- The National Library of Scotland

- An excellent source for many things. Unsurprisingly, especially good for Scottish and UK content.

- The National Galleries of Scotland

- Surprisingly deep wells of content. These generally need uploaded with a {{PD-Art}} or {{PD-Scan}} wrapper template, but weirdly enough, they actually encourage use on Wikipedia, so ... there's that. I'll explain wrapper templates below in their own section.

- The Royal Collections Trust

- A bit variable, but when it gives you something good, it's very good. They do falsely claim copyright on a lot of images they in no way have copyright on; use {{PD-Scan}} or {{PD-Art}} as a wrapper template for the copyright tag, as explained below.

France

- Gallica (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

- This is an absolutely incredible and deep source. From the archives of French Newspapers, the collections of the Paris Opera, to 18th century battle illustrations. Uploading files is a little complex; see Commons:Gallica.

Australia

- The Trove

- Indexes so many Australian libraries and museums. An amazing resource. Fairly easy to use once you get used to the slightly weird way of clicking off to the main museum/library/etc. site where you can actually download things.

New Zealand

- Te Papa Tongarewa (Museum of New Zealand)

- Search, click on "Unrestricted use" or "Some Reuse / Creative Commons" in the column on the left, and get great images. Really easy to use.

Norway

- National Library of Norway

- "Bilder" is Norwegian for "Pictures", so if you click on that after a search you'll get the images you're looking for. Other than the language barrier, it's honestly pretty easy.

The Netherlands

- Nationaal Archief

- Easier to search for names, but there's a surprisingly robust collection of celebrity photographs that have been released to the public domain. Weird quirk of the site: Figuring out copyright tags can be a little tough. As they explain elsewhere, if it has a download button, it's free to use, generally because the Nationaal Archief is the copyright holder and released it to the public domain, meaning the {{CC-zero}} copyright template should be used. That said, I think there's a reason I've restored a few of their images, but generally ones other people have found.

Worldwide

- Google Arts and Culture

- Great selection of images from a load of museums and libraries worldwide, newly scanned. A little hard to extract unless you know the trick: Just go to the page for the artwork, grab the URL, and paste it into https://dezoomify.ophir.dev/

- Flickr

- Kind of old-school nowadays. But if you choose advanced options for a search, you can choose "No copyright restrictions" or "Creative Commons" and you might find something. I mean, the Prime Minister of Ukraine apparently has a Flickr account. so that's cool. If you click on the little down-pointing arrow in the lower right you can download the largest possible size, but don't do this, just use https://flickr2commons.toolforge.org/#/ and it'll do everything for you, all the documentation, easy!

- If it's the Flickr account of a major archive or library, it can be worth looking up the image on the institution's website and seeing if it's available in higher resolution or with more documentation there.

- Just Google it

- Works more often than you'd think. Used to be a lot easier to find higher-resolution copies of images with Google, but nowadays I find I have to use Bing for that. EU lawsuit, I think.

Getting the images when they don't want you to |

There's three main methods you can try:

- Paste the URL into https://dezoomify.ophir.dev/. This will handle most zoomable images quickly and easily.

- Use Firefox, hit Ctrl-I, which gets you into a tool called "Page Info". Go to the "Media" tab, scroll through the list until you find the full-resolution copy of the file. Check the URL address for the image doesn't include something like width=500 – sometimes you can get a bigger copy by changing that to, say, width=10000 and play around from there.

- Beg for help on Commons:Village Pump.

Copyright |

Image copyright probably deserves its own article, but let's at least cover some common cases. Commons requires that an image be out of copyright both in the United States and its country of origin; English Wikipedia only requires it be out of copyright in the United States. Commons:Copyright rules by territory covers the situation for a lot of countries in a complex, over-detailed way. So here's a very simple guide. If it says something's definitely out of copyright, it should always be right; but there are a number of additional cases where things might be out of copyright that it doesn't include.

For works created outside of the United States, and presuming it's not an anonymous work, you'll need to know the year the photographer or creator died. If you can't find it, see if it comes under {{PD-old-assumed}}, which basically says that if you can't find the date of death, but the work is more than 120 years old[1]; if it's more than 190 years old[2] since we know the maximum human lifespan, just treat it as fully out of copyright (Use {{PD-old-70-expired}}. To find the date of death, first of all, I find libraries often misread names from old cabinet cards if they're written in artistic enough of a font, so check whether there's other readings of the text on them. A Google search for, say, "Bogardus photographer" can sometimes lead you directly to the result; Wikidata also has details for a lot of people, with sources, if you can get enough of their name.

Note that copyright only expires at the end of each calendar year. So, if it says below that a country uses, say, Life + 70 years, then if a creator expired exactly 70 years ago today, Life + 70 will expire 1 January next year. I've tried to phrase things as unambiguously as I could ("1928 or before" instead of "before 1929", for example), but writing "expires at midnight on the January 1 after 70 years have passed since the date of their death" is a little too unweildy.

If the image ....

- ... is a work of the U.S. Federal government: Use {{PD-USGov}}

- Exception: if the main focus of the image[3] is a heraldic emblem (badges, medals, unit insignia and such), use {{PD-USGov-Military-Army-USAIOH}} instead.

- ... has been released under a Creative Commons or similar license by the rights holder: Use whatever it's been released under.

- ... was published in 1928 or before...

- ... and it's a US work: Use {{PD-US-expired}}.

- ... and the creator died more than 70 years ago: This is generally good to go. The template is {{PD-old-auto-expired|deathyear=XXXX}} where XXXX is the year the last surviving creator died. Exceptions: There are seven countries with copyright terms longer than life + 70, listed below. See List of countries' copyright lengths to see which have terms shorter than 70.

- 75 years ago: Guatemala, Honduras

- 80 years ago: Columbia, Equatorial Guinea, Spain

- 95 years ago: Jamaica

- 100 years ago: Mexico.

- The same {{PD-old-auto-expired|deathyear=XXXX}} applies to these if it's applicable.

- Russia and France have some weird additional rules, which rarely apply. Note that Russian copyright can't be extended past Life+74 years, but France can extend copyright for death in active service. That said, most French images are probably being grabbed from Gallica, and Gallica marks works that are out of copyright.

- ...is by an anonymous creator: If it's a US work, then go back up to "...and it's a US work". Otherwise, as long as you have a good source for it being anonymous (a major library or museum saying it is is usually good enough), then, generally, anything 70 years post publication in Europe (80 for Spain) is fine, and the rest of the world ... ask on Commons:Village pump/Copyright. Here's the list of templates:

- UK: {{PD-UK-unknown}}

- Ireland: {{PD-Ireland-anon}}

- EU: {{PD-anon-70-EU}}

- Spain: {{PD-Spain-anon-80}}

- See Commons:Category:PD-anon_license_tags for others, and then read what the text says.

- literally anything published in 1928 or before: If there's still any doubts, anything from 1928 or before can always be uploaded here (not Commons) and labelled {{PD-US-expired-abroad}}

What kind of other cases are there?

- Works from the United States of America

- For American copyright, just look at the Hirtle chart. And despair! ...Okay, that's not fair, it's actually a really clear guide to navigating United States copyright. But proving things are out of copyright under some of its provisions can be difficult. For example, for specifically United States works between 1929 and 1963, copyright had to be renewed in order to maintain it. If you can prove an image wasn't renewed, then it's fine to use. But check out File:Carmen Miranda in That Night in Rio (1941).jpg#Licensing for the kind of research that has to be done to prove that.

- The simplest additional case is works from 1977 or before published without a copyright notice. You'll need to make sure it wasn't cropped out, you'll need to check the whole work (so the entire issue of a newspaper, or front and back of a postcard), and you'll need to make sure the work unambiguously originates in America. But, if they don't use the proper form, it's out of copyright. This happened all the time, perhaps most famously with Night of the Living Dead.

- Works from everywhere else:

- As I said, literally anything published in 1928 or before can always be uploaded here (not Commons) and labelled {{PD-US-expired-abroad}}. Since every file has to be out of copyright in the United States to be uploaded here, and I was focusing on the 1928 or before way of checking American copyright, and Life+70 is so common of a requirement for other countries, I didn't list the countries with requirements less than Life+70. As such, there's going to be some additional cases where something I said to upload under {{PD-US-expired-abroad}} could have been uploaded to Commons if you checked Commons:Copyright rules by territory and went to the appropriate country. That gets confusing though.

- If a work was out of copyright in its home country before the URAA date.... This one's a nightmare. See, the US doesn't use the "rule of the shortest term", wherein if a work was out of copyright in its home country, OR by the terms set out under U.S. law, it would be out of copyright. It just uses U.S. law. Except, not quite: The U.S., for a long time, didn't respect foreign copyright at all, so if you published a work as a British citizen, it'd be instantly free to use and out of copyright in the United States. It brought copyright protection in gradually, but the long story short is, if it was out of copyright in its home country in 1996 (usually, sometimes later), then it's out of copyright in America, otherwise, follow American rules, except the ones about needing to renew copyright... it's complex enough that it'd probably need that full-length article on copyright.

- Statutory releases: For example, Crown Copyright generally expires worldwide. UK Crown Copyright only lasts 50 years from creation, for example, which puts a lot of UK works about, say, WWII out of copyright. That said, it's weirdly applied, like giving Winston Churchill copyright on recordings of his governmental speeches. Which might not hold up if you challenged it, but, uh... you want to do the lawsuit?

There's also a lot of things that are specific to one country that's hard to cover. For example, any photograph from Japan from before 1957 is out of copyright both there and America, because the copyright term for photographs was only 10 years after creation until 1957. Some countries refuse copyright to "simple photographs"... and then you have to dig into case law to find out what that means. Commons:Copyright rules by territory is an overwhelming nightmare, but if you're going to be working with a specific country's content, it's worth checking that country's page to see what exceptions might apply. But I hope this section at least gives you a guide to understanding the easier cases.

If the museum or library claims copyright on a two-dimensional image, but going through the list above says it's out of copyright, then we acknowledge that the hosting site says that, then upload it anyway. (If it's a picture of a statue or other significantly three-dimensional artwork, they have a valid claim.) This is done using a wrapper template.

{{PD-Scan}} is used when it's a mere scan of the image, the kind of thing you'd get by putting a photograph on a scanner, and clicking the "Scan" button, and then maybe giving it some minor levels tweaks. {{PD-Art}} is a little more general and a little more restrictive, it's for if, say, someone took a photograph of a painting, where they might have had to adjust things slightly more. If you're not sure, just use {{PD-Art}}. Also, {{PD-Scan}} is only on Commons, so if you're uploading on English Wikipedia, always use {{PD-Art}}.

So, let's say you've worked out from about that the copyright tag should be {{PD-old-auto-expired|deathyear=1903}}. It's a mere scan of a photograph, so we can use the slightly stronger {{PD-Scan}} template. So, we just kind of add PD-Scan in front of the other bits of the template, so it becomes: {{PD-Scan|PD-old-auto-expired|deathyear=1903}}.

Documenting an image |

Commons has a certain number of tools to help you do this. I... tend not to use them. So, let's just look at the basic {{Information}} template, because you can always use the tools, then go back and edit it to add anything you missed.

{{Information

|Description=

|Source=

|Date=

|Author=

|Permission=

|other_versions=

}}

That's the basic information template. There's also {{Artwork}} and a few others, but they're much harder to use, and some of them have this weird self-checking code for what you put into them that doesn't always work right, and then... Ech. Just... don't, and use {{Information}} if you value your sanity.

If the image you're uploading is the original file, add {{Original}} above the information template. This tells people that this is the original file, you should upload any modified versions as their own file. We'll talk about why that's a good thing more in the next section, but, for now, let's cover everything else, using File:David Livingstone by Thomas Annan - Original.jpg as an example. The image source for it is [2].

- Description

- This is where you put most of the information that doesn't fit elsewhere. Ideally you should link to the Wikipedia articles for things described, but that's ... not as easy as I'd like: you have to use the format [[:en:PAGENAME|PAGENAME]], so don't worry too much about it.

- The description for the David Livingstone image is:

"David Livingstone, 1813–1873. Missionary and explorer", a carbon print of a photograph by Thomas Annan, 36.90 × 30.20 cm. Gift to the National Galleries of Scotland by T & R Annan and Sons, 1930. Let's go through this, making a rough order that information should appear in. - If an image is heavily modified in a way that's not really trying to respect the original intent, like desaturating it, that's fine to do, but it's better to mention it straight out. So you might begin, "Greyscale version of..." Upload the original version first, though, I explain why below.

- Start with the title of the image, or the subject if the image is untitled: The National Galleries of Scotland names this image as "David Livingstone, 1813–1873. Missionary and explorer". Was that its original title? Probably not; it dates from 1864, after all, but there's no competing titles, so let's use it. We put it in quotes since it's a title; if it didn't have a title assigned, we'd just use David Livingstone (not in quotes).

- If the title doesn't do a good job of explaining the subject of the image, explain it. For example, if the image had been named The Explorer, we might write "The Explorer, a photograph of David Livingstone." Sometimes, this might be quite long, for example, explaining a battle and where and when in it the photograph was taken. You can include references, and future article writers might thank you if you do.

- Give basic details about the image, as opposed to the subject. By which I mean things like "Oil painting", "charcoal and ink drawing", "daguerrotype" and such; as much as your source gives you This is specifically a carbon print, which is a way of printing a photograph, and, while we don't have to say it's by Thomas Annan here, it doesn't hurt. If we didn't know it was a carbon print, this bit might work to just "A photograph by Thomas Annan", or if the explanation above went long, we might just bluntly list the fact at the end as "Carbon print, 36.90 × 30.20 cm." On which subject ...

- If you know the size of the image, give the size. This image is 36.90 × 30.20 cm.

- Anything else? The museum mentions the instrument of gift, this probably isn't very important, but we'll list it here. More important information, though, might be including a transcription of text written on the image, especially if it's written somewhere that it might end up cropped off, or if it's written on the back of the image. Just say what you can.

- That done, the rest is pretty easy.

- Source

- A link to the page you got it from, wikilinked to the name of the museum. This is a good place to put the accession number. Some sites have special templates to make things easier. If you're going to use a site a lot, it's worth getting used to these, such as {{Loc}} for the Library of Congress and {{Gallica}} for Gallica/Bibliothèque National de France. It's worth checking your link works, though. Future Wikipedians will thank you.

- Date

- Possibly simple, possibly you'll want to include a reference for this where you detail your extensive efforts to narrow down when the image is from. There's bots that'll automatically internationalise the date for you, so don't worry too much.

- Author

- The artist, photographer, etc. If there's a publisher and a creator, the publisher generally gets mentioned in the description instead. Give the years of birth and death if at all possible. A lot of creators have special templates on Commons, in the rough form {{Creator:Thomas Annan}}. It's often worth just trying the name and seeing if a creator template exists.

- Permission

- You can put the copyright template here, or put it under the information template. I don't know why they made there be multiple acceptable formats.

- other_versions

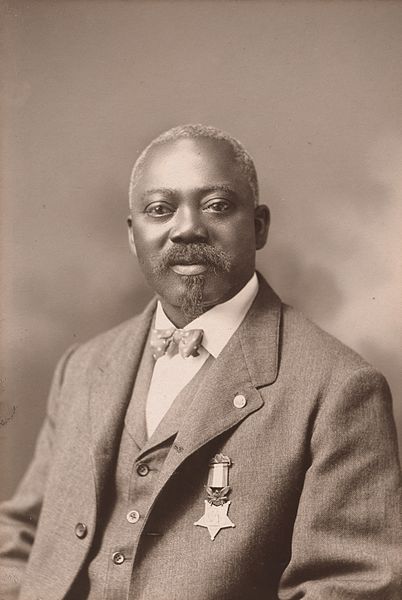

- This is where you link between the different versions of files, because being able to compare images to see what was done to them is important part of documenting your work. I like to do this as a simple list of links, and include the file you're looking at, because a link to the page you're on just shows up as text in bold so it shows you where you are in the file set instantly, and makes clear the connections between them. In this case, there's just the original file, and a JPEG and PNG of the restoration; the PNG is because repeatedly editing a JPEG will degrade the image because JPEGs are lossy, so it's worth including a PNG copy, because then you can go back and fix things if you spot an error later. This can get more complex: Consider File:Thomas Mundy Peterson by William R. Tobias.jpg, where there's good reasons to use the full card: it's a souvenir of an event where Thomas Mundy Peterson was given a medal for being the first African-American to vote under the 15th Amendment, but there's also going to be cases where you'd want a cropped version, and so I provided one and cleaned up the edges a little bit.

Having done that, add the copyright statement below the information template if you haven't put it into |Permission= – I still don't know why we have two accepted variants for that, and add a few categories if you can. You can then copy all of this for any other versions of the file, making any changes necessary.

So you want to modify the image? |

I don't want you to be afraid to modify an image. This whole section boils down to "Upload a copy of the original image first, upload your changes as a separate file, and link your modified image to the original version." Because, with a little care, and remembering that subtle changes are often better than huge changes (and pretty much always better than autolevels), you can probably make a better copy of the original image for use on Wikipedia. However, it's misleading to present an altered image as an unaltered original, and it's possible to get an image that genuinely looks better, but, for example, blows out some of the whites, so that information is lost that could have been saved while getting it to look just as nice. If you uploaded the original, this "even better" option is still on the table later, but your copy can be used until that version exists.

So, that said, I'm going to talk about a lot of things that can go wrong. But I don't want to discourage you from trying, just encouraging you to use good image editing behaviour.

First, upload the original to Commons. Mark it with {{Original}} to tell people not to alter it. Make sure that you upload your altered copies as separate images, and link these images to the original image you just uploaded, stating explicitly that this new copy has been modified.

The documentation is important. Look at these two images of SMS Von der Tann:

Despite the obvious differences, these both claim to be the same image, an exact upload of the original source. One isn't. The second one is the actual original file from the Library of Congress. Nothing on the file description page for the first one – at least at time of writing – makes it clear that the first one has been modified in any way.

It's not really a problem to do a bad image adjustment if you've given people the tools to consider how you did by showing people what the image looked like before you did anything.

A good rule of thumb is to look at your image, and look at the original. As long as there's an obvious improvement – and not just at thumbnail: we ideally want people to use our articles as sources to help them find resources as well as information – and you've linked to a copy of the original, everything's great.

And for the record, this "Upload the original image" guide applies to:

- Cropping the image

- First of all, this can hide the fact that more of the person's pose and body exists. But even when it's just to remove a frame, this can lead to problems. It's actually shocking how many times I've seen an image credited to "Unknown photographer", when the name of the photographer was literally right there on the image itself before it was cropped.

- Desaturating a sepia image

- I think this often makes a rather good image look like a bad photocopy, but it can work, and a lot of images did exist in both sepia and black and white. But if you're making a decision to change a historical image for artistic reasons, then it's vitally important that you let people know that you've made that decision in the first place. This is one of those changes that's not one that people will presume you made as part of preparing an image so you need to explicitly state that it has been done in the first line or so of the image's description.

- Levels adjustments

- It's pretty easy to get this wrong, and there's no real way to document your work without having the original image to compare it to.

- "But Adam, can't people just click through to the site and look at the original that way?"

Sites change their layout all the time, and many once-free sites now don't allow download of their originals. There's a few cases where someone's mangled an image, but clearly had access to a copy I wish I could work on – but I can't.

Image restoration |

Some images are better for a first-time restorationist than others. Take the following examples, each of which is the original file that a recentish featured restoration was based on.

My rule of thumb is that a first-time restorationist should have a reasonable shot at completing their restoration. If something is too difficult to restore it's just going to result in frustration.

French battleship Justice

First of all, the work in restoring an image is, to some extent, proportional to the image's size. This image is 10,212 × 8,097 pixels in size. Not a great start to things. While one can, in theory, crop it a bit, it's still going to be quite large, and it might result in a poor image composition.

Secondly, while parts of the image aren't too bad, the left edge of this image is appalling. Here's a before-and-after restoration comparison:

| Before | After |

|---|---|

|

|

That level of damage took me around 10–15 hours of work just for that little bit on the left hand side (I'm not sure I'm not underestimating that time) and that's with me being highly efficient as I've been doing this for years. Admittedly, it's on the left edge, so you could crop a bit, but it's not clear if you could crop enough to actually make things reasonable without the ship ending up way too tightly cropped. Reviewing an image beforehand to check for problem areas is a good first step before considering restoration. This also gives you a chance to try to figure out anything that might be mistaken for damage but isn't, such as portholes that show up as dark spots on the image, but aren't damage unlike those other dark spots.

Percy Grainger

It has cracks on the negative, and the pieces are slightly misaligned. One can use a careful hand with the select tool to realign them, then restore over the cracks, but cracks, lines, and other such things are relatively hard: the "healing brush" tool can be thrown by the change in colour leaving clear signs of where they were, and they often intersect detailed parts of the image that need carefully pattern matched.

William Harvey Carney

Had I not already restored this one, this would be a pretty good choice for a novice restorationist. There's a tiny bit of weird damage in the lower left, which is small enough to be fairly easy to fix, or it could be cropped out with little damage to composition. There's some damage a bit higher up on the left intruding in from the left hand side, but it's over a bit of non-detailed background that doesn't really matter, so whatever you do to fix it it's not going to look terrible. The rest of the damage is pretty much isolated spots, which are easily fixed with even a half-careful use of the healing brush.

Of course, selecting images is the first step. I'll cover how to do the restoration in another article, but, for now:

I use GIMP, the GNU Image Manipulation Program, which is free. For basic damage, I like to use the healing brush tool, with a hardness 100 brush, set to a size just slightly bigger than the spots, (generally not bigger than about 12px wide), selecting as the source of the pattern something as close to the damaged area as possible when the patterns are detailed (it matters a lot less with tiny damage spots on relatively flat areas of colour.

The clone stamp is sometimes needed where there's a hole or large damage and the healing stamp would change the colours too much; for that I like the hardness 75 brush as it helps it blend in.

The dodge and burn tools, at generally very low opacities (2–10%) and like, a hardness 25 brush, can be quite useful for dealing with areas that are lighter or darker than they should be – like fading – but they handle colour somewhat badly if you try to take it too far. Size depends on what you're fixing; a lot of the time the lightened area has a certain width, so you want to try to match that. Other times I want it quite large. Just hit undo if it's not right the first time. This is probably the easiest one of these to get wrong, saving only ...

Levels and curves: I find it's better to be a lot more subtle than you'd think. Don't use autolevels; it's generally absolutely terrible. You'll often need to nudge saturation down a little bit after a large change in levels, as the colours can end up very over-saturated.

Footnotes |

- ^ Exceptions for the 120 years old: 125 for works from Guatemala and Honduras; 130 years ago for Columbia, Equatorial Guinea, and Spain; 145 years ago for Jamaica; and 150 years ago for Mexico.

- ^ Exceptions for the 190 years old: 195 for works from Guatemala and Honduras; 200 years ago for Columbia, Equatorial Guinea, and Spain; 215 years ago for Jamaica; and 220 years ago for Mexico,

- ^ Basically, it doesn't matter if there happens to be an emblem on display if it's incidental to the main image. Like if someone's sitting in an office and a plaque is on their desk.

Getting serious about writing

As part of our attempts to publish lost Signpost articles, to give glimpses into history, we have an article originally intended for April 2019, describing changes to the Signpost's backend that took place at that time. We've been benefiting from them for so long that perhaps we don't remember how bad things used to be, so here's a report from the time, excited for the improvements. It also provides a lot of notes on using these features that might well help new contributors.

- For real: be careful using this as a guide! Some of the templates and processes introduced in this are already gone.

The Signpost has been hard at work to streamline its submission process and make the behind-the-scenes grunt work more manageable. Writing for us and getting involved has never been easier! Here is a short overview of the changes that happened since mid March.

-

Before refitting: Come cross a very small and calm lake with us. Our boat floats! Bring your own life jackets.

-

After refitting: Come cross the Atlantic with us. Our boat can take hurricanes and rogue waves!

The Signpost gets a shakeup

For those that follow The Signpost, there was a big shakeup recently, resulting in new blood on the team (see Signpost coverage). While Smallbones is now the new editor-in-chief, I've decided to include myself (Headbomb) as a general editor, mostly focusing on copy-editing, writing special pieces and polishing the technical aspects of The Signpost.

The shakeup left the team with a very short amount of time to cobble together the previous issue of The Signpost, with a generally positive reception. While I can't speak for Smallbones (who said that 'getting the issue out was a great experience'), I felt there was very steep learning curve to getting involved and that a lot of things were needlessly complicated, involved pointless busywork, were poorly documented, or relied on someone else knowing how to do something.

We have been putting up call for volunteers and writers for years without much success. But we failed to ask ourselves who wants to work on a boat where you can't get out of your cabin because the door is rusted shut? Possibly because we were too busy patching holes in the hull while at sea. So for this issue, instead of being a random passerby taking on the task of mending sails during the middle of a hurricane, I figure I'd take The Signpost to the shipyard for a long overdue refit. I don't know that getting involved at The Signpost is now as easy as 1-2-3, but it certainly is easier than ever before.

Simpler management

A lot stuff changed behind the scenes to make The Signpost easier to manage and collaborate on. Big ticket changes include

- A redesigned look for the newsroom and its talkpage. These pages are better organized with less clutter, and feature an improved {{Signpost/Deadline}} tracker. Among other things, the tracker now includes a link to a timezone converter so deadlines can be known in local time.

- A major overhaul in the newsroom's functionality. Three main components were overhauled

- The newsroom now automatically synchronizes itself with the {{Signpost draft}} templates present on draft articles from the next issue. If you mark a draft from the next issue as ready to be copy edited, the newsroom will reflect that automatically.

- The newsroom now features Recent changes/See also links that make it easier to monitor changes related to the current and next issues, as well as links to other Signpost-like newsletter in other languages with English translations.

- The introduction section now offers clearer, less intimidating directions to people who want to help and get involved. The clickable buttons are now consistent with those from the submissions and suggestions pages and will present friendlier preloaded forms.

- We now have a live mockup of the next issue to give a quick overview of how the next issue is shaping up. Note that it will not be very interesting to look at right after publication given that work on the next issue will not have started just yet.

- {{Signpost series}} has been dusted off and modernized. The modernization of Mr. Stradivarius's tag manager script is in progress, but it remains functional. Better documentation is still needed, but article series can be reintroduced when relevant.

- The template / HTML structure behind the 'two-column' and 'full width' styles has been greatly streamlined and made compatible with each other, allowing to easily switch between one style to the other if desired. Which style is used is now explicitely controlled with

|fullwidth=no/yesin relevant templates, with|fullwidth=no(two-column style) being used by default.

All of this should allow the editorial team to focus on content, rather than waste time managing things across dozens of pages and obscure template / HTML issues. If you go to the newsroom, everything is there within a click or two: the current status of the next issue, upcoming deadlines, recent changes, reader comments, and more.

Simpler writing

While improvements to the management aspects of The Signpost will save the team a lot of headaches, writers and readers that want to get involved were not forgotten. Big ticket changes included

- Better guidance about where to do what is provided in general. It is now much less confusing to get around the various pages of The Signpost. Buttons with preloaded forms were added when missing, or polished to be less confusing.

- Do you know of an exciting story that should be covered? Click on suggestions!

- Do you plan on writing an article or want to submit a draft for review? Click on proposals/submissions!

- You can now easily create user drafts with the new 'create a draft button'. This will allow you to work on articles in your user space. This is very useful if you have an idea for a special column, but need time to work on it.

- All drafts created through the newsroom have had their preloaded forms overhauled. They now all feature simpler/clearer/more useful instructions.

- The {{Signpost draft}} template now has a lot more useful information and writer resources, including deadlines and submit buttons for user space drafts.

- Signpost drafts now have editable sections, like regular articles. The [edit] button next to sections is now only disabled in published articles.

- The {{Signpost draft helper}} template is now featured at the bottom of every draft created via the 'create a draft' button in the newsroom. The template explains how to create the syntax of many common elements, like images and quotations, and how to control two-column vs full width styles.

What it all means

These efforts, which would not have been nearly as successful without the help of DannyS712, Evad37, Pppery, TheDJ, have made it simpler than ever to contribute to the The Signpost! No longer do you need to be a template guru with a deep knowledge of an arcane, Rube Golberg-like, syntax! No more getting lost and confused!

Want to get involved? Then your one stop is the newsroom (WP:NEWSROOM)! If you can make your way there, the rest is an easy click or two away. And if you are content remaining a reader, you can sleep soundly knowing that The Signpost team can now spend more of its time on bringing you the best content instead of doing busywork.

If you have suggestions on how to make contributing to The Signpost more user friendly, leave us a comment below (or at WT:SIGNPOST). Happy editing!

Copyright trolls, or the last beautiful free souls on this planet?

Preserving the integrity of Creative Commons: a creator's perspective

In the dynamic world of Wikimedia Commons, where photographers like me share our works with the public under free Creative Commons licenses, one crucial aspect has sparked heated debates: enforcement. As a photographer passionate about fostering collaboration and creativity, I strongly believe that enforcing these licenses with greater diligence is necessary to protect the integrity of our contributions.

Empowering collaboration through free licenses

As creators, our primary goal is to contribute to the collective pool of knowledge and inspire others through our art. By embracing free Creative Commons licenses, we empower fellow creators to build upon our works and foster a culture of open collaboration. The essence of Wikimedia Commons lies in the ability of diverse minds to come together, create, and share freely.

License disregard – a challenging dilemma

Despite our commitment to openness, instances of license violations do occur. When our works are used without proper attribution or without adhering to the license terms we've chosen, it becomes a matter of principle to address such violations. We are not copyright trolls; we are creators who wish to protect the essence of Creative Commons – the idea that sharing and collaboration should go hand in hand with proper recognition and adherence to license requirements.

Enforcing compliance with our chosen licenses is an act of responsibility, not hostility. It is a necessary measure to protect the collaborative environment we cherish. Just as any artist deserves acknowledgment for their masterpieces, we, too, deserve the credit and recognition for our creative efforts.

Preserving fairness and respect for creators

As creators who wholeheartedly contribute to the wealth of knowledge on Wikimedia Commons, we firmly believe that our works should be used according to the licenses we have carefully selected. The decision to license our creations under Creative Commons is a deliberate one, driven by our commitment to openness and collaboration. We willingly embrace the spirit of sharing, hoping to inspire others and contribute to a collective platform that benefits society as a whole.

However, when these licenses are ignored or undermined, it poses a significant challenge to the very foundation of what we stand for as creators. Seeking monetary compensation when our licenses are disregarded is not about adopting a hostile stance or becoming copyright trolls, but rather about preserving fairness and respect for the artistic contributions we have made.

Our chosen Creative Commons licenses are not arbitrary; they are a conscious reflection of how we wish our works to be used and attributed. As photographers, artists, and creators, we invest our time, energy, and passion into crafting meaningful content. We acknowledge that sharing should not come at the cost of eroding the rights and recognition we deserve as authors.

A balanced approach to enforcement is essential, one that upholds the principles of Creative Commons while promoting a culture of respect for creators. We are not seeking punitive measures, but rather a fair acknowledgment that our works are valuable and deserving of recognition. By doing so, we reinforce the credibility of Creative Commons as a powerful framework that fosters creativity and collaboration.

In seeking compliance with our licenses, we are not stifling the spirit of sharing; rather, we are nurturing an environment where mutual respect between creators and users flourishes. Striking this balance enables us to inspire future generations of artists and contributors, confident in the knowledge that their works will be cherished and used responsibly.

It is crucial to remember that enforcing Creative Commons licenses is not about hindering access to knowledge or preventing creativity; on the contrary, it is about preserving the very essence of our shared contributions. Through the fair enforcement of these licenses, we protect the foundation upon which Wikimedia Commons thrives—a place where ideas converge, creativity is celebrated, and knowledge is democratized for the benefit of all.

A desire to enforce the terms of our chosen licenses should not be misconstrued as an antagonistic act but as a means to ensure that the culture of openness and collaboration we hold dear remains intact. By preserving fairness and respect for creators, we are fostering a vibrant and sustainable community that continues to inspire, educate, and shape the world through our collective artistic endeavors. It is through this shared dedication to the principles of Creative Commons that we can uphold the true spirit of Wikimedia Commons and its transformative power in the realm of knowledge and creativity.

My image theft notice

As a dedicated photographer on Wikimedia Commons, I value transparency in enforcing the licenses for my images. To address image theft concerns, I include a notice on my uploads:

"This image is protected against image theft.

Failure to comply with the license may result in legal or monetary liabilities. I use Pixsy to monitor, find, and fight image theft. Please follow the specified license to avoid infringement."

I do this to provide re-users with a clear warning and to maintain an open and transparent approach in enforcing the terms of the license when they are disregarded.

Counter-arguments against enforcement

While some creators advocate for stricter enforcement of Creative Commons licenses, there are counter-arguments that highlight potential drawbacks to this approach. One concern is that overly aggressive enforcement might be perceived as punitive or profit-seeking, going against the very essence of Creative Commons' principles. Such perceptions could potentially deter users from engaging with the free culture and collaborative spirit that Creative Commons seeks to promote.