| 1804 Haiti massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution | |

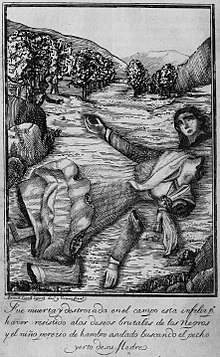

Engraving depicting a killing during the massacre | |

| Location | First Empire of Haiti |

| Date | February 1804 – 22 April 1804 |

| Target | French people |

Attack type | Massacre, genocide[1] |

| Deaths | 3,000–7,000 |

| Injured | Unknown |

| Perpetrators | Army of Jean-Jacques Dessalines |

| Motive | Anti-French sentiment Revenge for slavery |

The 1804 Haiti massacre, also referred to as the Haitian genocide,[1][2][3] was carried out by Afro-Haitian soldiers, mostly former slaves, under orders from Jean-Jacques Dessalines against much of the remaining European population in Haiti, which mainly included French people.[4][5] The Haitian Revolution defeated the French army in November 1803 and the Haitian Declaration of Independence happened on 1 January 1804.[6] From February 1804[7] until 22 April 1804, between 3,000 and 7,000 people were killed.[7]

Based on the book "An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti" written by Marcus Rainsford, a British soldier who served for many years with the British Army in the British West Indies, in 1805. In his book, Rainsford provides extensive documentation of the revolution, offering disturbing accounts of the brutal treatment of the enslaved population by their French masters, as well as the atrocities committed by all sides during the conflict. He also presented an original copy of the decree signed by Dessaline in February 1804.[8]

The massacre excluded surviving Polish Legionnaires, who had defected from the French legion to become allied with the enslaved Africans, as well as the Germans who did not take part of the slave trade. They were instead granted full citizenship under the constitution and classified as Noir, the new ruling ethnicity.[9][page needed]

Nicholas Robins, Adam Jones, and Dirk Moses theorize that the executions were a "subaltern genocide", in which an oppressed group uses genocidal means to destroy its oppressors.[10][11] Philippe Girard has suggested the threat of reinvasion and reinstatement of slavery as some of the reasons for the massacre.[12]

Throughout the early-to-mid nineteenth century, the events of the massacre were well known in the United States. Additionally, many Saint Dominican refugees moved from Saint-Domingue to the U.S., settling in New Orleans, Charleston, New York, Baltimore, and other coastal cities. These events spurred fears of potential uprisings in the Southern U.S. and they also polarized public opinion on the question of the abolition of slavery.[13][14]

- ^ a b Girard (2005a), pp. 158–159.

- ^ Moses & Stone (2013), p. 63.

- ^ Forde (2020), p. 40.

- ^ Rogers (2010), p. 353.

- ^ Orizio (2001), pp. 149, 157–159.

- ^ Sutherland, Claudia (16 July 2007). "Haitian Revolution (1791–1804)". Blackpast.org. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ a b Girard (2011), pp. 319–322.

- ^ Gaffield, Julia (26 January 2016). "Dessalines Reader, 29 February 1804". Haiti and the Atlantic World. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Girard (2011).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Robins & Joneswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Klävers (2019), p. 110.

- ^ Girard (2005a).

- ^ Julius, Kevin C. (2004). The abolitionist decade, 1829–1838 : a year-by-year history of early events in the antislavery movement. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-1946-6.[page needed]

- ^ Marcotte, Frank B. (2005). Six days in April : Lincoln and the Union in peril. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 0-8758-6313-2.