| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

County results

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Tennessee |

|---|

|

|

|

The 1892 United States presidential election in Tennessee took place on November 8, 1892. All contemporary 44 states were part of the 1892 United States presidential election. Tennessee voters chose twelve electors to the Electoral College, which selected the president and vice president.

For over a century after the Civil War, Tennessee’s white citizenry was divided according to partisan loyalties established in that war. Unionist regions covering almost all of East Tennessee, Kentucky Pennyroyal-allied Macon County, and the five West Tennessee Highland Rim counties of Carroll, Henderson, McNairy, Hardin and Wayne[1] voted Republican – generally by landslide margins – as they saw the Democratic Party as the “war party” who had forced them into a war they did not wish to fight.[2] Contrariwise, the rest of Middle and West Tennessee who had supported and driven the state’s secession was equally fiercely Democratic as it associated the Republicans with Reconstruction.[3] After the state’s white landowning class re-established its rule in the early 1870s, black and Unionist white combined to forge adequate support for the GOP to produce a competitive political system for two decades,[4] although during this era the Republicans could only capture statewide offices when the Democratic Party was divided on this issue of payment of state debt.[4]

White Democrats in West Tennessee were always aiming to eliminate black political influence, which they first attempted to do by election fraud in the middle 1880s and did so much more successfully at the end of the decade by instituting in counties with significant black populations a secret ballot that prevented illiterates voting,[5] and a poll tax throughout the state.[6]

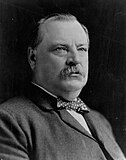

At the time of the next presidential election, third-time Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland was extremely concerned with the lack of loyalty to the gold standard by Tennessee Democrats and the growing influence of the James B. Weaver-led Populist Party over the state, especially after Governor John P. Buchanan joined the Populists and ran for re-election under that party’s banner[7] However, the strong emphasis by Cleveland and running mate Adlai Stevenson I on opposing the Lodge Force Bill and on reducing tariffs was able to minimise defections to the Populists or the GOP – which with large Unionist areas was even with incomplete black disenfranchisement more viable than in any other ex-Confederate state.[7] Stevenson’s extensive tour of Tennessee and his campaign against the Populists ensured that the state was won comfortably against incumbent President and Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison, whose vote total declined by thirty-eight thousand or over a quarter due to the loss of black voters.

- ^ Wright, John K.; ‘Voting Habits in the United States: A Note on Two Maps’; Geographical Review, vol. 22, no. 4 (October 1932), pp. 666-672

- ^ Key (Jr.), Valdimer Orlando; Southern Politics in State and Nation (New York, 1949), pp. 282-283

- ^ Lyons, William; Scheb (II), John M. and Stair Billy; Government and Politics in Tennessee, pp. 183-184 ISBN 1572331410

- ^ a b Kousser, J. Morgan; The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910, p. 104 ISBN 0-300-01973-4

- ^ Kousser; The Shaping of Southern Politics, p. 110

- ^ Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics, p. 118

- ^ a b Sclup, Leonard; ‘Conservative Counterattack: Adlai E. Stevenson and the Compromise of 1892 with Democrats in Tennessee and the South’; Tennessee Historical Quarterly; Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer 1994), pp. 114-129