Fakhr-e-Afghan Sarhadi Gandhi Abdul Ghaffar Khan | |

|---|---|

عبدالغفار خان | |

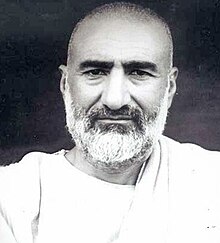

Ghaffar Khan c. 1940s | |

| Born | 6 February 1890 |

| Died | 20 January 1988 (aged 97) Peshawar, North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan |

| Resting place | Jalalabad, Afghanistan |

| Nationality |

|

| Education | Aligarh Muslim University |

| Title | Bacha Khan/Badshah Khan[2] |

| Political party |

|

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

| Spouses | Meharqanda Kinankhel

(m. 1912–1918)Nambata Kinankhel

(m. 1920–1926) |

| Children | 5, including |

| Parent | Abdul Bahram Khan (father) |

| Relatives | Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan (brother) |

| Awards |

|

Abdul Ghaffār Khān (Pashto: عبدالغفار خان; 6 February 1890 – 20 January 1988), also known as Bacha Khan (Pashto: باچا خان) or Badshah Khan (بادشاه خان, 'King of Chiefs'), was an Indian independence activist from the North-West Frontier Province, and founder of the Khudai Khidmatgar resistance movement against British colonial rule in India.[3]

He was a political and spiritual leader known for his nonviolent opposition and lifelong pacifism; he was a devout Muslim and an advocate for Hindu–Muslim unity in the subcontinent.[4] Due to his similar ideologies and close friendship with Mahatma Gandhi, Khan was nicknamed Sarhadi Gandhi (सरहदी गांधी, 'the Frontier Gandhi').[5][6] In 1929, Khan founded the Khudai Khidmatgar, an anti-colonial nonviolent resistance movement.[7] The Khudai Khidmatgar's success and popularity eventually prompted the colonial government to launch numerous crackdowns against Khan and his supporters; the Khudai Khidmatgar experienced some of the most severe repression of the entire Indian independence movement.[8]

Khan strongly opposed the proposal for the Partition of India into the Muslim-majority Dominion of Pakistan and the Hindu-majority Dominion of India, and consequently sided with the pro-union Indian National Congress and All-India Azad Muslim Conference against the pro-partition All-India Muslim League.[9][10][11] When the Indian National Congress reluctantly declared its acceptance of the partition plan without consulting the Khudai Khidmatgar leaders, he felt deeply betrayed, telling the Congress leaders "you have thrown us to the wolves."[12] In June 1947, Khan and other Khudai Khidmatgar leaders formally issued the Bannu Resolution to the British authorities, demanding that the ethnic Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan, which was to comprise all of the Pashtun territories of British India and not be included (as almost all other Muslim-majority provinces were) within the state of Pakistan—the creation of which was still underway at the time. However, the British government refused the demands of this resolution.[13][14] In response, Khan and his elder brother, Abdul Jabbar Khan, boycotted the 1947 North-West Frontier Province referendum on whether the province should be merged with India or Pakistan, objecting that it did not offer options for the Pashtun-majority province to become independent or to join neighbouring Afghanistan.[15][16]

After the Partition of India by the British government, Khan pledged allegiance to the newly created nation of Pakistan, and stayed in the now-Pakistani North-West Frontier Province; he was frequently arrested by the Pakistani government between 1948 and 1954.[17][18] In 1956, he was arrested for his opposition to the One Unit program, under which the government announced its plan to merge all the provinces of West Pakistan into a single unit to match the political structure of erstwhile East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh). Khan was jailed or in exile during some years of the 1960s and 1970s. He was awarded Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, by the Indian government in 1987.

Following his will upon his death in Peshawar in 1988, he was buried at his house in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Tens of thousands of mourners attended his funeral including Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah, marching through the Khyber Pass from Peshawar towards Jalalabad. It was marred by two bomb explosions that killed 15 people; despite the heavy fighting at the time due to the Soviet–Afghan War, both sides, namely the Soviet–Afghan government coalition and the Afghan mujahideen, declared an immediate ceasefire to allow Khan's burial.[19] He was given military honors by the Afghan government.

- ^ Manishika, Meena (2021). Biography of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan: Inspirational Biographies for Children. Prabhat Prakashan.

- ^ Ahmad, Aijaz (2005). "Frontier Gandhi: Reflections on Muslim Nationalism in India". Social Scientist. 33 (1/2): 22–39. JSTOR 3518159.

- ^ Hamling, Anna (16 October 2019). Contemporary Icons of Nonviolence. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-4173-3.

- ^ An American Witness to India's Partition by Phillips Talbot, (2007), Sage Publications ISBN 978-0-7619-3618-3

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "Uttarakhand journalist gave Frontier Gandhi title to Abdul Gaffar Khan, claims book". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Raza, Moonis; Ahmad, Aijazuddin (1990). An Atlas of Tribal India: With Computed Tables of District-level Data and Its Geographical Interpretation. Concept Publishing Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-8170222866.

- ^ Burrell, David B. (7 January 2014). Towards a Jewish-Christian-Muslim Theology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-118-72411-8.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Zartmanwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Abdul Ghaffar Khan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ "Abdul Ghaffar Khan". I Love India. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017). Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1108621236.

- ^ "Partition and Military Succession Documents from the U.S. National Archives".

- ^ Ali Shah, Sayyid Vaqar (1993). Marwat, Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan (ed.). Afghanistan and the Frontier. University of Michigan: Emjay Books International. p. 256.

- ^ H Johnson, Thomas; Zellen, Barry (2014). Culture, Conflict, and Counterinsurgency. Stanford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0804789219.

- ^ Meyer, Karl E. (2008). The Dust of Empire: The Race For Mastery in the Asian Heartland – Karl E. Meyer – Google Boeken. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-0786724819. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Was Jinnah democratic? — II". Daily Times. 25 December 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

BKTwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jaffrelot2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

15-killedwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).