Abdus Salam | |

|---|---|

عبد السلام | |

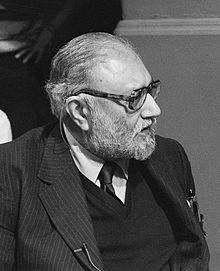

Salam in 1987 | |

| Born | 29 January 1926 |

| Died | 21 November 1996 (aged 70) Oxford, England |

| Nationality | British Indian (1926–1947) Pakistani (1947–1996) |

| Alma mater | Government College University (BA) University of the Punjab (MA) St John's College, Cambridge (PhD) |

| Known for | |

| Spouse | Amtul Hafeez Begum

(m. 1949–1996) |

| Children | 6 |

| Awards | Smith's Prize (1950) Adams Prize (1958) Sitara-e-Pakistan (1959) Hughes Medal (1964) Atoms for Peace Prize (1968) Royal Medal (1978) Matteucci Medal (1978) Nobel Prize in Physics (1979) Nishan-e-Imtiaz (1979) Lomonosov Gold Medal (1983) Copley Medal (1990) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Developments in quantum theory of fields (1952) |

| Doctoral advisor | Nicholas Kemmer |

| Other academic advisors | Paul Matthews |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students | |

| Signature | |

| |

Mohammad Abdus Salam[4][5][6] NI(M) SPk (/sæˈlæm/; pronounced [əbd̪ʊs səlaːm]; 29 January 1926 – 21 November 1996)[7] was a Pakistani theoretical physicist. He shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg for his contribution to the electroweak unification theory.[8] He was the first Pakistani and the first scientist from an Islamic country to receive a Nobel Prize and the second from an Islamic country to receive any Nobel Prize, after Anwar Sadat of Egypt.[9]

Salam was scientific advisor to the Ministry of Science and Technology in Pakistan from 1960 to 1974, a position from which he played a major and influential role in the development of the country's science infrastructure.[9][10] Salam contributed to numerous developments in theoretical and particle physics in Pakistan.[10] He was the founding director of the Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO), and responsible for the establishment of the Theoretical Physics Group (TPG).[11][12] For this, he is viewed as the "scientific father"[5][13] of this program.[14][15][16] In 1974, Abdus Salam departed from his country in protest after the Parliament of Pakistan unanimously passed a parliamentary bill declaring members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, to which Salam belonged, non-Muslim.[17] In 1998, following the country's Chagai-I nuclear tests, the Government of Pakistan issued a commemorative stamp, as a part of "Scientists of Pakistan", to honour the services of Salam.[18]

Salam's notable achievements include the Pati–Salam model, a Grand Unified Theory he proposed along with Jogesh Pati in 1974, magnetic photon, vector meson, work on supersymmetry and most importantly, electroweak theory, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize.[8] Salam made a major contribution in quantum field theory and in the advancement of Mathematics at Imperial College London. With his student, Riazuddin, Salam made important contributions to the modern theory on neutrinos, neutron stars and black holes, as well as the work on modernising quantum mechanics and quantum field theory. As a teacher and science promoter, Salam is remembered as a founder and scientific father of mathematical and theoretical physics in Pakistan during his term as the chief scientific advisor to the president.[10][19] Salam heavily contributed to the rise of Pakistani physics within the global physics community.[20][21] Up until shortly before his death, Salam continued to contribute to physics, and to advocate for the development of science in third-world countries.[22]

- ^ Fraser 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Ashmore, Jonathan Felix (2016). "Paul Fatt. 13 January 1924 – 28 September 2014". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 62. London: 167–186. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2016.0005. ISSN 0080-4606.

- ^ Cheema, Hasham (29 January 2018). "Abdus Salam: The real story of Pakistan's Nobel prize winner". Dawn.

- ^ Fraser 2008, p. 249 Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard.

- ^ a b Rizvi, Murtaza (21 November 2011). "Salaam Abdus Salam". Dawn. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

Mohammad Abdus Salam (1926–1996) was his full name, which may add to the knowledge of those who wish he was either not Ahmadi or Pakistani. He was given the task of Pakistan's atomic bomb programme, as well as Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission to resolve energy crisis and Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO). Unfortunately he failed in all the three fields.

- ^ This is the standard transliteration (e.g. see the ICTP Website Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine and Nobel Bio). See Abd as-Salam for more details.

- ^ Aziz, K.K (2008). The coffee house of Lahore (1st ed.). Lahore, Pakistan: Sang-e-Meel Publication. p. 200. ISBN 9789693520934.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "1979 Nobel Prize in Physics". Nobel Prize. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014.

- ^ a b (Ghani 1982, pp. i–xi)

- ^ a b c Riazuddin (21 November 1998). "Physics in Pakistan". ICTP. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ (Rahman 1998, pp. 75–76)

- ^ Abbot, Sebastian (9 July 2012). "Pakistan shuns physicist linked to "God Particle"". Yahoo! News. p. 1. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Salam wielded significant influence in Pakistan as the chief scientific adviser to the president, helping to set up the country's space agency and the institute for nuclear science and technology. Salam also worked in the early stages of Pakistan's effort to build a nuclear bomb, which it eventually tested in 1998

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Muslim Times, Lahorewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Scientists asked to emulate Dr Salam's achievements". Dawn. 7 October 2004. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ (Rahman 1998, pp. 10–101)

- ^ "Re-engineering Pakistan and Physics from Pakistan Conference:MQM Stays loyal with Pakistan Armed Forces". Jang News Group. Jang Media Cell and MQM Science and Technology Wing. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, and other prominent scientists, have made Pakistan, a nuclear power. All of these scientists were poor or Muhajir (migrants from India), says Altaf Hussain.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Philately (21 November 1998). "Scientists of Pakistan". Pakistan Post Office Department. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Abdus Salam, As I Know him: Riazuddin, NCP

- ^ Ishfaq Ahmad (21 November 1998). "CERN and Pakistan: a personal perspective". CERN Courier. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Riazuddin (21 November 1998). "Pakistan Physics Centre". ICTP. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "Abdus Salam -Biography". Nobel Prize Committee.