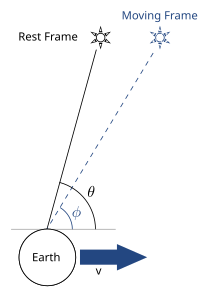

In astronomy, aberration (also referred to as astronomical aberration, stellar aberration, or velocity aberration) is a phenomenon where celestial objects exhibit an apparent motion about their true positions based on the velocity of the observer: It causes objects to appear to be displaced towards the observer's direction of motion. The change in angle is of the order of where is the speed of light and the velocity of the observer. In the case of "stellar" or "annual" aberration, the apparent position of a star to an observer on Earth varies periodically over the course of a year as the Earth's velocity changes as it revolves around the Sun, by a maximum angle of approximately 20 arcseconds in right ascension or declination.

The term aberration has historically been used to refer to a number of related phenomena concerning the propagation of light in moving bodies.[1] Aberration is distinct from parallax, which is a change in the apparent position of a relatively nearby object, as measured by a moving observer, relative to more distant objects that define a reference frame. The amount of parallax depends on the distance of the object from the observer, whereas aberration does not. Aberration is also related to light-time correction and relativistic beaming, although it is often considered separately from these effects.

Aberration is historically significant because of its role in the development of the theories of light, electromagnetism and, ultimately, the theory of special relativity. It was first observed in the late 1600s by astronomers searching for stellar parallax in order to confirm the heliocentric model of the Solar System. However, it was not understood at the time to be a different phenomenon.[2] In 1727, James Bradley provided a classical explanation for it in terms of the finite speed of light relative to the motion of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun,[3][4] which he used to make one of the earliest measurements of the speed of light. However, Bradley's theory was incompatible with 19th-century theories of light, and aberration became a major motivation for the aether drag theories of Augustin Fresnel (in 1818) and G. G. Stokes (in 1845), and for Hendrik Lorentz's aether theory of electromagnetism in 1892. The aberration of light, together with Lorentz's elaboration of Maxwell's electrodynamics, the moving magnet and conductor problem, the negative aether drift experiments, as well as the Fizeau experiment, led Albert Einstein to develop the theory of special relativity in 1905, which presents a general form of the equation for aberration in terms of such theory.[5]

- ^ Schaffner, Kenneth F. (1972). Nineteenth-century aether theories. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 99–117 und 255–273. ISBN 0-08-015674-6.

- ^ Williams, M. E. W. (1979). "Flamsteed's Alleged Measurement of Annual Parallax for the Pole Star". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 10 (2): 102–116. Bibcode:1979JHA....10..102W. doi:10.1177/002182867901000203. S2CID 118565124.

- ^ Bradley, James (1727–1728). "A Letter from the Reverend Mr. James Bradley Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, and F.R.S. to Dr.Edmond Halley Astronom. Reg. &c. Giving an Account of a New Discovered Motion of the Fix'd Stars". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 35 (406): 637–661. Bibcode:1727RSPT...35..637B. doi:10.1098/rstl.1727.0064.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Alan (2001). Parallax:The Race to Measure the Cosmos. New York, New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-7133-4.

- ^ Norton, John D. (2004). "Einstein's Investigations of Galilean Covariant Electrodynamics prior to 1905". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 59 (1): 45–105. Bibcode:2004AHES...59...45N. doi:10.1007/s00407-004-0085-6. S2CID 17459755. Archived from the original on 2009-01-11.