| Acinetobacter baumannii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Pseudomonadales |

| Family: | Moraxellaceae |

| Genus: | Acinetobacter |

| Species: | A. baumannii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii Bouvet and Grimont 1986[1]

| |

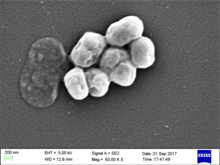

Acinetobacter baumannii is a typically short, almost round, rod-shaped (coccobacillus) Gram-negative bacterium. It is named after the bacteriologist Paul Baumann.[2] It can be an opportunistic pathogen in humans, affecting people with compromised immune systems, and is becoming increasingly important as a hospital-derived (nosocomial) infection. While other species of the genus Acinetobacter are often found in soil samples (leading to the common misconception that A. baumannii is a soil organism, too), it is almost exclusively isolated from hospital environments.[3] Although occasionally it has been found in environmental soil and water samples,[4] its natural habitat is still not known.[citation needed]

Bacteria of this genus lack flagella but exhibit twitching or swarming motility, likely mediated by type IV pili. Motility in A. baumannii may also be due to the excretion of exopolysaccharide, creating a film of high-molecular-weight sugar chains behind the bacterium to move forward.[5] Clinical microbiologists typically differentiate members of the genus Acinetobacter from other Moraxellaceae by performing an oxidase test, as Acinetobacter spp. are the only members of the Moraxellaceae to lack cytochrome c oxidases.[6]

A. baumannii is part of the ACB complex (A. baumannii, A. calcoaceticus, and Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). It is difficult to determine the specific species of members of the ACB complex and they comprise the most clinically relevant members of the genus.[7][8] A. baumannii has also been identified as an ESKAPE pathogen (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species), a group of pathogens with a high rate of antibiotic resistance that are responsible for the majority of nosocomial infections.[9]

Colloquially, A. baumannii is referred to as "Iraqibacter" due to its seemingly sudden emergence in military treatment facilities during the Iraq War.[10] It has continued to be an issue for veterans and soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Multidrug-resistant A. baumannii has spread to civilian hospitals in part due to the transport of infected soldiers through multiple medical facilities.[5] During the COVID-19 pandemic, coinfection with A. baumannii secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infections has been reported multiple times in medical publications.[11]

- ^ Parte, A.C. "Acinetobacter". LPSN.

- ^ Lin, Ming-Feng; Lan, Chung-Yu (2014). "Antimicrobial Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: From Bench to Bedside". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2 (12): 787–814. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.787. PMC 4266826. PMID 25516853.

- ^ Antunes, Luísa C.S.; Visca, Paolo; Towner, Kevin J. (August 2014). "Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen". Pathogens and Disease. 71 (3): 292–301. doi:10.1111/2049-632X.12125. PMID 24376225. S2CID 30201194.

- ^ Yeom, Jinki; Shin, Ji-Hyun; Yang, Ji-Young; Kim, Jungmin; Hwang, Geum-Sook; Bundy, Jacob Guy (6 March 2013). "1H NMR-Based Metabolite Profiling of Planktonic and Biofilm Cells in Acinetobacter baumannii 1656-2". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e57730. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857730Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057730. PMC 3590295. PMID 23483923.

- ^ a b McQueary, Christin N.; Kirkup, Benjamin C.; Si, Yuanzheng; Barlow, Miriam; Actis, Luis A.; Craft, David W.; Zurawski, Daniel V. (30 June 2012). "Extracellular stress and lipopolysaccharide modulate Acinetobacter baumannii surface-associated motility". Journal of Microbiology. 50 (3): 434–443. doi:10.1007/s12275-012-1555-1. PMID 22752907. S2CID 18294862.

- ^ Garrity, G., ed. (2000). "Pts. A & B: The Proteobacteria". Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-387-95040-2.

- ^ O'Shea, MK (May 2012). "Acinetobacter in modern warfare". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 39 (5): 363–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.018. PMID 22459899.

- ^ Gerner-Smidt, P (October 1992). "Ribotyping of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 30 (10): 2680–5. doi:10.1128/JCM.30.10.2680-2685.1992. PMC 270498. PMID 1383266.

- ^ Rice, LB (15 April 2008). "Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (8): 1079–81. doi:10.1086/533452. PMID 18419525.

- ^ Drummond, Katie (2010-05-24). "Pentagon to Troop-Killing Superbugs: Resistance Is Futile". Wired.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Kyriakidis, I; Vasileiou, E; Pana, Z-D; Tragiannidis, A (2021). "Acinetobacter baumannii Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms". Pathogens. 10 (373): 373. doi:10.3390/pathogens10030373. PMC 8003822. PMID 33808905.