This article contains too many quotations. (April 2024) |

Sultanate of Adal سلطنة عدل (Arabic) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1415–1577 | |||||||||

|

The combined three banners used by Ahmad al-Ghazi's forces | |||||||||

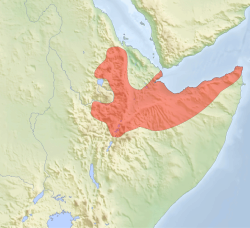

The Adal Sultanate in c. 1540 | |||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Government | Kingdom | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

• 1415–1423 (first) | Sabr ad-Din III | ||||||||

• 1577 (last) | Muhammad Gasa | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | 1415 | ||||||||

• Sabr ad-Din III returns from exile in Yemen | 1415 | ||||||||

• War with Yeshaq I | 1415–1429 | ||||||||

• Succession Crisis | 1518–1526 | ||||||||

| 1529–1543 | |||||||||

• Disestablished | 1577 | ||||||||

| Currency | Ashrafi[2] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Adal Sultanate, also known as the Adal Empire or Bar Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling Adel Sultanate, Adal Sultanate) (Arabic: سلطنة عدل), was a medieval Sunni Muslim Empire which was located in the Horn of Africa.[3] It was founded by Sabr ad-Din III on the Harar plateau in Adal after the fall of the Sultanate of Ifat.[4] The kingdom flourished c. 1415 to 1577.[5] At its height, the polity under Sultan Badlay controlled the territory stretching from Cape Guardafui in Somalia to the port city of Suakin in Sudan.[6][7][8][9][10][11] The Adal Empire maintained a robust commercial and political relationship with the Ottoman Empire.[12] Sultanate of Adal was alternatively known as the federation of Zeila.[13]

- ^ Telles, Balthazar (1710). The Travels of the Jesuits in Ethiopia (1st ed.). J. Knapton.

It might perhaps be to called from Abaxa, the Capital City of the Kingdom of Adel.

- ^ Zekaria, Ahmed (1991). "Harari Coins: A Preliminary Survey". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 24: 24. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 41965992. Archived from the original on 2022-12-31. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^ Ta'a, Tesema (2002). ""Bribing the Land": An Appraisal of the Farming Systems of the Maccaa Oromo in Wallagga". Northeast African Studies. 9 (3). Michigan State University Press: 99. doi:10.1353/nas.2007.0016. JSTOR 41931282. S2CID 201750719. Archived from the original on 2021-05-20. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Ahmed, Hussein (2007). "Reflections on Historical and Contemporary Islam in Ethiopia and Somalia: A Comparative and Contrastive Overview". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 40 (1/2). Institute of Ethiopian Studies: 264. JSTOR 41988230. Archived from the original on 2023-02-01. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ Elrich 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Pradines, Stéphane (7 November 2022). Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa From Timbuktu to Zanzibar. BRILL. p. 127. ISBN 9789004472617. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Braukamper, Ulrich (2002). Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia. Lit. p. 33. ISBN 9783825856717. Archived from the original on 2024-05-22. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

- ^ Owens, Travis. BELEAGUERED MUSLIM FORTRESSES AND ETHIOPIAN IMPERIAL EXPANSION FROM THE 13TH TO THE 16TH CENTURY (PDF). NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020.

- ^ Pouwels, Randall (31 March 2000). The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780821444610. Archived from the original on 18 September 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Leo, Africanus; Pory, John; Brown, Robert (1896). The history and description of Africa. Harvard University. London, Printed for the Hakluyt society. pp. 51–53.

- ^ Hassan, Mohamed. The Oromo of Ethiopia: A History, 1570-1860. p. 35.

- ^ Salvadore, Matteo (2016). The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations, 1402–1555. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-1317045465. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ Brill, E. J. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. A - Bābā Beg · Volume 1. Brill. p. 126. ISBN 9789004097872. Archived from the original on 2024-05-22. Retrieved 2023-07-07.