| Quran |

|---|

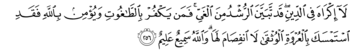

The verse (ayah) 256 of Al-Baqara is a very famous verse in the Islamic scripture, the Quran.[1] The verse includes the phrase that "there is no compulsion in religion".[2] Immediately after making this statement, the Quran offers a rationale for it: Since the revelation has, through explanation, clarification, and repetition, clearly distinguished the path of guidance from the path of misguidance, it is now up to people to choose the one or the other path.[1] This verse comes right after the Throne Verse.[3]

The overwhelming majority of Muslim scholars consider that verse to be a Medinan one,[4][5][6] when Muslims lived in their period of political ascendance,[7][8] and to be non abrogated,[9] including Ibn Taymiyya,[10] Ibn Qayyim,[11] Al-Tabari,[12] Abi ʿUbayd,[13] Al-Jaṣṣās,[14] Makki bin Abi Talib,[15] Al-Nahhas,[16] Ibn Jizziy,[17] Al-Suyuti,[18] Ibn Ashur,[19] Mustafa Zayd,[20] and many others.[21] According to all the theories of language elaborated by Muslim legal scholars, the Quranic proclamation that 'There is no compulsion in religion. The right path has been distinguished from error' is as absolute and universal a statement as one finds,[22] and so under no condition should an individual be forced to accept a religion or belief against his or her will according to the Quran.[23][24][25][26]

The meaning of the principle that there is no compulsion in religion was not limited to freedom of individuals to choose their own religion. Islam also provided non-Muslims with considerable economic, cultural, and administrative rights.[27]

- ^ a b Mustansir Mir (2008), Understanding the Islamic Scripture, p. 54. Routledge. ISBN 978-0321355737.

- ^ Quran 2:256

- ^ Jacques Berque (1995), Le Coran : Essai de traduction, p.63, note v.256, éditions Albin Michel, Paris.

- ^ John Esposito (2011), What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam, p. 91. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979413-3.

- ^ Sir Thomas Walker Arnold (1913), Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith, p. 6. Constable.

- ^ Mapel, D.R. and Nardin, T., eds. (1999), International Society: Diverse Ethical Perspectives, p. 233. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691049724.

- ^ Taha Jabir Alalwani (2003), La 'ikraha fi al-din: 'ichkaliyat al-riddah wa al-murtaddin min sadr al-Islam hatta al-yawm, pp.92-93. ISBN 9770909963.

- ^ "this verse is acknowledged to belong to the period of Quranic revelation corresponding to the political and military ascendance of the young Muslim community. ‘There is no compulsion in religion’ was not a command to Muslims to remain steadfast in the face of the desire of their oppressors to force them to renounce their faith, but was a reminder to Muslims themselves, once they had attained power, that they could not force another's heart to believe. There is no compulsion in religion addresses those in a position of strength, not weakness. The earliest commentaries on the Quran (such as that of Al-Tabari) make it clear that some Muslims of Medina wanted to force their children to convert from Judaism or Christianity to Islam, and this verse was precisely an answer to them not to try to force their children to convert to Islam." Open Letter to his holiness Pope Benedict XVI (PDF) Archived 2009-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Richard Curtis (2010), Reasonable Perspectives on Religion, p. 204. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739141892. Quote: "While the pope, following many anti-Islam propagandists, seemingly argues that the oft-cited Quranic dictum "no compulsion in religion" was abrogated by subsequent revelations, this is not the mainstream Muslim interpretation. Indeed, the pope made a major scholarly blunder when he claimed that the "no compulsion in religion" verse was revealed during the Meccan period, "when Mohammed was still powerless and under threat." In fact, it was revealed during the later Medinan period--the same period as the verses that authorize armed struggle against the Meccan enemies of the nascent Muslim community in Medina, that is, "when Muhammad was in a position of strength, not weakness."" (emphasis added)

- ^ Ibn Taymiyya, Qāʿidah Mukhtaṣarah fī Qitāl al-Kuffār wa Muhādanatihim wa Taḥrīm Qatlihim li-Mujarrad Kufrihim: Qāʿidah Tubayyn al-Qiyam al-Sāmiyah lil-Haḍārah al-Islāmiyyah fī al-Harb wa al-Qitāl, p.123. Ed. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn ʿAbd Allah ibn Ibrāhīm al-Zayd Āl Hamad. Riyadh: N.p., 2004/1424. Quote: "جمهور السلف و الخلف على أنها ليست مخصوصة و لا منسوخة، ..." Translation: "Most of the salaf considered the verse to be neither specific nor abrogated but the text is general, ..."

- ^ Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, Ahkam Ahl al-Dhimma, pp.21-22.

- ^ Al-Tabari, Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan ta'wīl āy al-Qur'ān 4, Dar Hajar, 2001, p.553.

- ^ Abi ʿUbayd, Kitab al-Nasikh wa al-Mansukh, p.282.

- ^ Al-Jaṣṣās, Aḥkām al-Qur'ān 2, p.168.

- ^ Makki bin Abi Talib, al-Idah li Nasikh al-Qur'an wa Mansukhih, p. 194.

- ^ Abu Jaʿfar al-Nahhas, al-Nasikh wa al-Mansukh fi al-Quran al-Karim, p.259.

- ^ Ibn Jizziy. at-Tasheel. p. 135.

- ^ Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti, Al-Itqān fi ʿUlum al-Qur’an 2. p.22-24.

- ^ Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur, Al-Tahrir wa al-Tanwir, (2:256).

- ^ Mustafa Zayd, al-Naskh fi al-Qur'an al-Karim 2, p.510. Dar al-Wafa'. Quote: "تبطل دعوى النسخ في قوله جل تناؤه:

لَا إِكْرَاهَ فِي الدِّينِ

لَا إِكْرَاهَ فِي الدِّينِ : ٢٥٦ في سورة البقرة."

: ٢٥٦ في سورة البقرة."

- ^ Muhammad S. Al-Awa (1993), Punishment in Islamic Law, p.51. US American Trust Publications. ISBN 978-0892591428.

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 186. ISBN 978-1780744209.

- ^ Yousif, Ahmad (2000-04-01). "Islam, Minorities and Religious Freedom: A Challenge to Modern Theory of Pluralism". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 20 (1): 35. doi:10.1080/13602000050008889. ISSN 1360-2004. S2CID 144025362.

- ^ Leonard J. Swidler (1986), Religious Liberty and Human Rights in Nations and in Religions, p.178. Ecumenical Press.

- ^ Farhad Malekian (2011), Principles of Islamic International Criminal Law, p.69. Brill. ISBN 978-9004203969.

- ^ Mohammad Hashim Kamali, The Middle Path of Moderation in Islam: The Qur'anic Principle of Wasatiyyah (Religion and Global Politics), pp. 110-1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190226831.

- ^ David Ray Griffin (2005), Deep Religious Pluralism, p.159. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664229146.