Alcohol and cancer have a complex relationship. Alcohol causes cancers of the oesophagus, liver, breast, colon, oral cavity, rectum, pharynx, and larynx, and probably causes cancers of the pancreas.[2][3] Cancer risk can occur even with light to moderate drinking.[4][5] The more alcohol is consumed, the higher the cancer risk,[6] and no amount can be considered completely safe.[7]

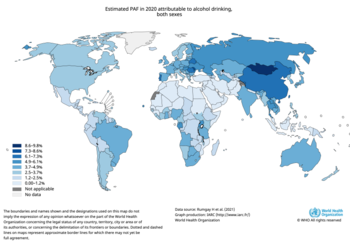

Alcoholic beverages were classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1988.[3] An estimated 3.6% of all cancer cases and 3.5% of cancer deaths worldwide are attributable to consumption of alcohol (more specifically, acetaldehyde, a metabolic derivative of ethanol).[8] 740,000 cases of cancer in 2020 or 4.1% of new cancer cases were attributed to alcohol.[3][2]

Alcohol is thought to cause cancer through three main mechanisms: (1) DNA methylation,[8] (2) Oxidative stress, and (3) Hormonal alteration. Additional mechanisms include microbiome dysbiosis, reduced immune system function, retinoid metabolism, increased levels of inflammation, 1-Carbon metabolism and disruption of folate absorption.[9]

Heavy drinking consisting of 15 or more drinks per week for men or 8 or more drinks per week for women beverages/week contributed the most to cancer incidence compared with moderate drinking. The rate of alcohol related cases is 3:1 male:female, especially in oesophageal and liver cancers.[3] Some nations have introduced alcohol packaging warning messages that inform consumers about alcohol and cancer. The alcohol industry has tried to actively mislead the public about the risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption, in addition to campaigning to remove laws that require alcoholic beverages to have cancer warning labels.

- ^ Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004 (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-92-4-156272-0.

- ^ a b "IARC: Home". www.iarc.who.int. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Rumgay H, Shield K, Charvat H, Ferrari P, Sornpaisarn B, Obot I, et al. (August 2021). "Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study". The Lancet. Oncology. 22 (8): 1071–1080. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5. PMC 8324483. PMID 34270924.

- ^ de Menezes RF, Bergmann A, Thuler LC (2013). "Alcohol consumption and risk of cancer: a systematic literature review". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 14 (9): 4965–72. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.9.4965. PMID 24175760.

- ^ Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, Scotti L, Jenab M, Turati F, Pasquali E, Pelucchi C, Bellocco R, Negri E, Corrao G, Rehm J, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C (February 2013). "Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta-analysis". Annals of Oncology. 24 (2): 301–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds337. PMID 22910838.

- ^ "Alcohol and Cancer Risk Fact Sheet - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 14 July 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". www.who.int. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ a b Varela-Rey M, Woodhoo A, Martinez-Chantar ML, Mato JM, Lu SC (2013). "Alcohol, DNA methylation, and cancer". Alcohol Research. 35 (1): 25–35. PMC 3860423. PMID 24313162.

- ^ Rumgay H, Murphy N, Ferrari P, Soerjomataram I (September 2021). "Alcohol and Cancer: Epidemiology and Biological Mechanisms". Nutrients. 13 (9): 3173. doi:10.3390/nu13093173. PMC 8470184. PMID 34579050.