| Alcoholism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Alcohol addiction, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol use disorder (AUD)[1] |

| |

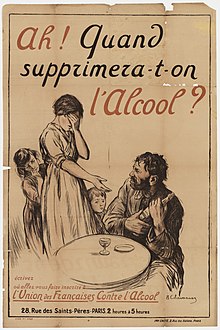

| A French temperance organisation poster depicting the effects of alcoholism in a family, c. 1915: "Ah! When will we be rid of alcohol?" | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology, toxicology, addiction medicine |

| Symptoms | Drinking large amounts of alcohol over a long period, difficulty cutting down, acquiring and drinking alcohol taking up a lot of time, usage resulting in problems, withdrawal occurring when stopping[2] |

| Complications | Mental illness, delirium, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, irregular heartbeat, cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, suicide[3][4][5][6] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic factors[4] |

| Risk factors | Stress, anxiety, easy access[4][7] |

| Diagnostic method | Questionnaires, blood tests[4] |

| Treatment | Alcohol cessation typically with benzodiazepines, counselling, acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone[8][9][10] Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other Twelve Step Programs, AA/Twelve Step Facilitation (AA/TSF)[11] |

| Frequency | 380 million / 5.1% adults (2016)[12][13] |

| Deaths | 3.3 million / 5.9%[14] |

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal.[15] Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 283 million people with alcohol use disorders worldwide as of 2016[update].[12][13] The term alcoholism was first coined in 1852,[16] but alcoholism and alcoholic are sometimes considered stigmatizing and to discourage seeking treatment, so diagnostic terms such as alcohol use disorder or alcohol dependence are often used instead in a clinical context.[17][18]

Alcohol is addictive, and heavy long-term alcohol use results in many negative health and social consequences. It can damage all the organ systems, but especially affects the brain, heart, liver, pancreas and immune system.[4][5] Heavy alcohol usage can result in trouble sleeping, and severe cognitive issues like dementia, brain damage, or Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. Physical effects include irregular heartbeat, an impaired immune response, liver cirrhosis, increased cancer risk, and severe withdrawal symptoms if stopped suddenly.[4][5][19] These health effects can reduce life expectancy by 10 years.[20] Drinking during pregnancy may harm the child's health,[3] and drunk driving increases the risk of traffic accidents. Alcoholism is also associated with increases in violent and non-violent crime.[21] While alcoholism directly resulted in 139,000 deaths worldwide in 2013,[22] in 2012 3.3 million deaths may be attributable globally to alcohol.[14]

The development of alcoholism is attributed to both environment and genetics equally.[4] The use of alcohol to self-medicate stress or anxiety can turn into alcoholism.[23] Someone with a parent or sibling with an alcohol use disorder is three to four times more likely to develop an alcohol use disorder themselves, but only a minority of them do.[4] Environmental factors include social, cultural and behavioral influences.[24] High stress levels and anxiety, as well as alcohol's inexpensive cost and easy accessibility, increase the risk.[4][7] People may continue to drink partly to prevent or improve symptoms of withdrawal.[4] After a person stops drinking alcohol, they may experience a low level of withdrawal lasting for months.[4] Medically, alcoholism is considered both a physical and mental illness.[25][26] Questionnaires are usually used to detect possible alcoholism.[4][27] Further information is then collected to confirm the diagnosis.[4]

Treatment of alcoholism may take several forms.[9] Due to medical problems that can occur during withdrawal, alcohol cessation should be controlled carefully.[9] One common method involves the use of benzodiazepine medications, such as diazepam.[9] These can be taken while admitted to a health care institution or individually.[9] The medications acamprosate or disulfiram may also be used to help prevent further drinking.[10] Mental illness or other addictions may complicate treatment.[28] Various individual or group therapy or support groups are used to attempt to keep a person from returning to alcoholism.[8][29] Among them is the abstinence based mutual aid fellowship Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). A 2020 scientific review found that clinical interventions encouraging increased participation in AA (AA/twelve step facilitation (AA/TSF))—resulted in higher abstinence rates over other clinical interventions, and most studies in the review found that AA/TSF led to lower health costs.[a][31][32][33]

Many terms, some slurs and some informal, have been used to refer to people affected by alcoholism such as tippler, drunkard, dipsomaniac and souse.[34]

- ^ "Alcoholism MeSH Descriptor Data 2020". meshb.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5". November 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Fetal Alcohol Exposure". 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5 ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 490–97. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ^ a b c "Alcohol's Effects on the Body". 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Borges G, Bagge CL, Cherpitel CJ, Conner KR, Orozco R, Rossow I (April 2017). "A meta-analysis of acute use of alcohol and the risk of suicide attempt". Psychological Medicine. 47 (5): 949–957. doi:10.1017/S0033291716002841. PMC 5340592. PMID 27928972.

- ^ a b Moonat S, Pandey SC (2012). "Stress, epigenetics, and alcoholism". Alcohol Research. 34 (4): 495–505. PMC 3860391. PMID 23584115.

- ^ a b Morgan-Lopez AA, Fals-Stewart W (May 2006). "Analytic complexities associated with group therapy in substance abuse treatment research: problems, recommendations, and future directions". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 14 (2): 265–73. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.265. PMC 4631029. PMID 16756430.

- ^ a b c d e Blondell RD (February 2005). "Ambulatory detoxification of patients with alcohol dependence". American Family Physician. 71 (3): 495–502. PMID 15712624.

- ^ a b Testino G, Leone S, Borro P (December 2014). "Treatment of alcohol dependence: recent progress and reduction of consumption". Minerva Medica. 105 (6): 447–66. PMID 25392958.

- ^ Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD012880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. PMC 7065341. PMID 32159228.

- ^ a b Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2018. pp. 72, 80. ISBN 978-92-4-156563-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects – Population Division". United Nations. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

NIH2015Statswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Littrell J (2014). Understanding and Treating Alcoholism Volume I: An Empirically Based Clinician's Handbook for the Treatment of Alcoholism: Volume II: Biological, Psychological, and Social Aspects of Alcohol Consumption and Abuse. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-317-78314-5. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017.

The World Health Organization defines alcoholism as any drinking which results in problems

- ^ Alcoholismus chronicus, eller Chronisk alkoholssjukdom. Stockholm und Leipzig. 1852. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ Morris J, Moss AC, Albery IP, Heather N (1 January 2022). "The 'alcoholic other': Harmful drinkers resist problem recognition to manage identity threat". Addictive Behaviors. 124: 107093. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107093. PMID 34500234. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Ashford RD, Brown AM, Curtis B (1 August 2018). "Substance use, recovery, and linguistics: The impact of word choice on explicit and implicit bias". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 189: 131–138. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.005. PMC 6330014. PMID 29913324.

- ^ Romeo J, Wärnberg J, Nova E, Díaz LE, Gómez-Martinez S, Marcos A (October 2007). "Moderate alcohol consumption and the immune system: a review". The British Journal of Nutrition. 98 (Suppl 1): S111-5. doi:10.1017/S0007114507838049. PMID 17922947.

- ^ Schuckit MA (November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens)". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113. S2CID 205116954. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Ritzer G, ed. (15 February 2007). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa039.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Moonat S, Pandey SC (2012). "[Stress, epigenetics, and alcoholism]". Alcohol Research. 34 (4): 495–505. PMC 3860391. PMID 23584115.

- ^ Agarwal-Kozlowski K, Agarwal DP (April 2000). "[Genetic predisposition for alcoholism]". Therapeutische Umschau. 57 (4): 179–84. doi:10.1024/0040-5930.57.4.179. PMID 10804873.

- ^ Mersy DJ (April 2003). "Recognition of alcohol and substance abuse". American Family Physician. 67 (7): 1529–32. PMID 12722853.

- ^ "Health and Ethics Policies of the AMA House of Delegates" (PDF). June 2008. p. 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

H-30.997 Dual Disease Classification of Alcoholism: The AMA reaffirms its policy endorsing the dual classification of alcoholism under both the psychiatric and medical sections of the International Classification of Diseases. (Res. 22, I-79; Reaffirmed: CLRPD Rep. B, I-89; Reaffirmed: CLRPD Rep. B, I-90; Reaffirmed by CSA Rep. 14, A-97; Reaffirmed: CSAPH Rep. 3, A-07)

- ^ Higgins-Biddle JC, Babor TF (2018). "A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: Past issues and future directions". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 44 (6): 578–586. doi:10.1080/00952990.2018.1456545. PMC 6217805. PMID 29723083.

- ^ DeVido JJ, Weiss RD (December 2012). "Treatment of the depressed alcoholic patient". Current Psychiatry Reports. 14 (6): 610–8. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0314-7. PMC 3712746. PMID 22907336.

- ^ Albanese AP (November 2012). "Management of alcohol abuse". Clinics in Liver Disease. 16 (4): 737–62. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.006. PMID 23101980.

- ^ Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (CD012880): 15. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. PMC 7065341. PMID 32159228.

- ^ Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD012880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. PMC 7065341. PMID 32159228.

- ^ Kelly JF, Abry A, Ferri M, Humphreys K (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and 12-Step Facilitation Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Distillation of a 2020 Cochrane Review for Clinicians and Policy Makers". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 55 (6): 641–651. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agaa050. PMC 8060988. PMID 32628263.

- ^ "Alcoholics Anonymous most effective path to alcohol abstinence". 2020. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Chambers English Thesaurus. Allied Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-81-86062-04-3.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).