| Part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Alternative cancer treatment describes any cancer treatment or practice that is not part of the conventional standard of cancer care.[2] These include special diets and exercises, chemicals, herbs, devices, and manual procedures. Most alternative cancer treatments do not have high-quality evidence supporting their use and many have been described as fundamentally pseudoscientific.[3][4][5][6] Concerns have been raised about the safety of some purported treatments and some have been found unsafe in clinical trials. Despite this, many untested and disproven treatments are used around the world.

Alternative cancer treatments are typically contrasted with experimental cancer treatments – science-based treatment methods – and complementary treatments, which are non-invasive practices used in combination with conventional treatment. All approved chemotherapy medications were considered experimental treatments before completing safety and efficacy testing.[citation needed]

Since the late 19th century, medical researchers have established modern cancer care through the development of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapies, and refined surgical techniques. As of 2019[update], only 32.9% of cancer patients in the United States died within five years of their diagnosis.[7] Despite their effectiveness, many conventional treatments are accompanied by a wide range of side effects, including pain, fatigue, and nausea.[8][9] Some side effects can even be life-threatening.[citation needed] Many supporters of alternative treatments claim increased effectiveness and decreased side effects when compared to conventional treatments. However, one retrospective cohort study showed that patients using alternative treatments instead of conventional treatments were 2.5 times more likely to die within five years.[10]

Most alternative cancer treatments have not been tested in proper clinical trials. Among studies that have been published, the quality is often poor. A 2006 review of 196 clinical trials that studied unconventional cancer treatments found a lack of early-phase testing, little rationale for dosing regimens, and poor statistical analyses.[11] These kinds of treatments have appeared and vanished throughout history.[12]

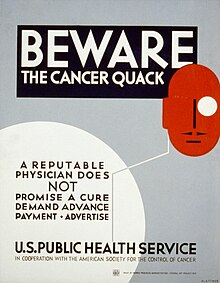

- ^ "Beware the cancer quack A reputable physician does not promise a cure, demand advance payment, advertise". Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) for Patients". National Cancer Institute. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pseudoscientificwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Vickers, AJ; Cassileth, BR (2008). "Living proof and the pseudoscience of alternative cancer treatments". Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 6 (1): 37–40. PMC 2630257. PMID 18302909.

- ^ Grimes, David Robert (1 January 2022). "The Struggle against Cancer Misinformation". Cancer Discovery. 12 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1468. eISSN 2159-8290. ISSN 2159-8274. PMID 34930788. S2CID 245373363.

This dubious amplification of pseudoscience diminishes trust in the medico-scientific sphere. Cancer misinformation is harmful even when it is not fully embraced or believed, precisely because it creates a lingering impression that no medical consensus exists on the topic or that official sources of information lack credibility.

- ^ Ernst, E (August 2001). "Alternative cancer cures". British Journal of Cancer. 85 (5): 781–782. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.1989. eISSN 1532-1827. ISSN 0007-0920. PMC 2364136. PMID 11531268.

Alternative cancer cures (ACCs) typically have a common life cycle (Ernst, 2000). At the origin of almost every ACC is a charismatic individual who claims to have found the answer to cancer. He (the male sex seems to dominate) often supports his claims with pseudoscientific evidence referring to (but rarely presenting) many cured patients. Thus he soon gathers ardent supporters who lobby for a wider acceptance of this ACC. The pressure on the medical establishment increases to a point where the treatment is finally submitted to adequate testing. When the results turn out to be negative, the ACC's proponents argue that the investigations were not done properly. In fact, they were set up to generate a negative result so that the commercial interests of orthodoxy would not be threatened. A conspiracy theory is thus born, and the ACC lives on in the 'alternative underground'.

- ^ "Cancer of All Sites – SEER Stat Fact Sheets". 12 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Sugerman, Deborah Tolmach (10 July 2013). "Chemotherapy". JAMA. 310 (2): 218. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.5525. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 23839767.

- ^ "Risks of Cancer Surgery". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Skyler B.; Park, Henry S.; Gross, Cary P.; Yu, James B. (2018). "Use of Alternative Medicine for Cancer and Its Impact on Survival". JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 110 (1): 121–124. doi:10.1093/jnci/djx145. PMID 28922780.

- ^ Vickers AJ, Kuo J, Cassileth BR (January 2006). "Unconventional anticancer agents: a systematic review of clinical trials". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (1): 136–40. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8406. PMC 1472241. PMID 16382123.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cassileth1996was invoked but never defined (see the help page).