A page from the Analects | |

| Author | Disciples of Confucius |

|---|---|

| Original title | 論語 |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Publication place | China |

Original text | 論語 at Chinese Wikisource |

| Translation | Analects at Wikisource |

| Analects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

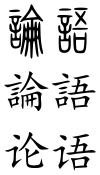

"Analects" written using seal script (top), as well as modern traditional (middle) and simplified (bottom) regular script character forms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 論語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 论语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lúnyǔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 'Selected sayings',[1] 'Edited conversations'[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Luận ngữ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 論語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 논어 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 論語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 論語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ろんご | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Analects, also known as the Sayings of Confucius, is an ancient Chinese philosophical text composed of sayings and ideas attributed to Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled by his followers.

The consensus among scholars is that large portions of the text were composed during the Warring States period (475–221 BC), and that the work achieved its final form during the mid-Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). During the early Han, the Analects was merely considered to be a commentary on the Five Classics. However, by the dynasty's end the status of the Analects had grown to being among the central texts of Confucianism.

During the late Song dynasty (960–1279 AD) the importance of the Analects as a Chinese philosophy work was raised above that of the older Five Classics, and it was recognized as one of the "Four Books". The Analects has been one of the most widely read and studied books in China for more than two millennia; its ideas continue to have a substantial influence on East Asian thought and values.

Confucius believed that the welfare of a country depended on the moral cultivation of its people, beginning from the nation's leadership. He believed that individuals could begin to cultivate an all-encompassing sense of virtue through ren, and that the most basic step to cultivating ren was filial piety—primarily the devotion to one's parents and older siblings.

He taught that one's individual desires do not need to be suppressed, but that people should be educated to reconcile their desires via li, rituals and forms of propriety, through which people could demonstrate their respect for others and their responsible roles in society. Confucius also believed that a ruler's sense of de, or 'virtue', was his primary prerequisite for leadership.

Confucius' primary goal in educating his students was to produce ethically well-cultivated men who would carry themselves with gravity, speak correctly, and demonstrate consummate integrity in all things.

- ^ Van Norden (2002), p. 12.

- ^ Knechtges & Shih (2010), p. 645.