Andranik | |

|---|---|

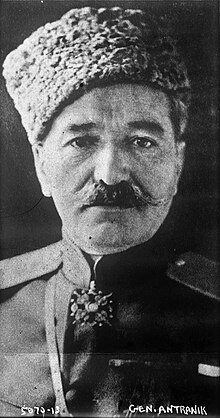

General Andranik Ozanian, wearing his uniform and medals with a papakha hat | |

| Nickname(s) | Andranik pasha[1] |

| Born | 25 February 1865 Shabin-Karahisar, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 31 August 1927 (aged 62) Richardson Springs, California, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Armenian paramilitaries (1917–19) |

| Years of service | 1888–1904 (fedayi) 1912–13 (Bulgaria) 1914–16 (WWI) 1917–19 (Armenia) |

| Rank | Commander of the fedayi (1899–1904)[2] Commander of the Western Armenian division of the Armenian Army Corps (1918) Commander of the Special Striking Division (1919) |

| Wars | |

| Awards | see below |

| Signature | |

Andranik Ozanian,[B] commonly known as General Andranik[4][C] or simply Andranik;[D] (25 February 1865 – 31 August 1927),[E] was an Armenian military commander and statesman, the best known fedayi[1][5][7] and a key figure of the Armenian national liberation movement.[8] From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, he was one of the main Armenian leaders of military efforts for the independence of Armenia.

He became active in an armed struggle against the Ottoman government and Kurdish irregulars in the late 1880s. Andranik joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktustyun) party and, along with other fedayi (militias), sought to defend the Armenian peasantry living in their ancestral homeland, an area known as Western (or Turkish) Armenia—at the time part of the Ottoman Empire. His revolutionary activities ceased and he left the Ottoman Empire after the unsuccessful uprising in Sasun in 1904. In 1907, Andranik left Dashnaktustyun because he disapproved of its cooperation with the Young Turks, a party which years later perpetrated the Armenian genocide. Between 1912 and 1913, together with Garegin Nzhdeh, Andranik led a few hundred Armenian volunteers within the Bulgarian army against the Ottomans during the First Balkan War.

From the early stages of World War I, Andranik commanded the first Armenian volunteer battalion within the Russian Imperial army against the Ottoman Empire, capturing and later governing much of the traditional Armenian homeland. After the Revolution of 1917, the Russian army retreated and left the Armenian irregulars outnumbered against the Turks. Andranik led the defense of Erzurum in early 1918, but was forced to retreat eastward due to an threat of encirclement and a lack of food. By May 1918, Turkish forces stood near Yerevan—the future Armenian capital—and were halted at the Battle of Sardarabad. The Dashnak-dominated Armenian National Council declared the independence of Armenia and signed the Treaty of Batum with the Ottoman Empire, by which Armenia gave up its rights to Western Armenia. Andranik never accepted the existence of the First Republic of Armenia because it included only a small part of the area many Armenians hoped to make independent. Andranik, independently from the Republic of Armenia, fought in Zangezur against the Azerbaijani and Turkish armies, and helped to keep it within Armenia.[9]

Andranik left Armenia in 1919 due to disagreements with the Armenian government and spent his last years of life in Europe and the United States seeking relief for Armenian refugees. He settled in Fresno, California in 1922 and died five years later in 1927. Andranik is greatly admired as a national hero by Armenians; numerous statues of him have been erected in several countries. Streets and squares were named after Andranik, and songs, poems and novels have been written about him, making him a legendary figure in Armenian culture.[10]

- ^ a b Libaridian, Gerard J. (1991). Armenia at the Crossroads: Democracy and Nationhood in the Post-Soviet Era. Watertown, Massachusetts: Blue Crane Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9628715-1-1.

- ^ Holding, Nicholas (2008). Armenia, with Nagorno Karabagh (2nd ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-84162-163-0.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hovannisian 1967was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Adalian 2010, p. 79.

- ^ a b Hovannisian, Richard G. (2000). Armenian Van/Vaspurakan. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-56859-130-8.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, p. 191.

- ^ Sarkisyanz, Manuel (1975). A Modern History of Transcaucasian Armenia: Social, Cultural, and Political. Leiden, Netherlands. p. 140. OCLC 8305411.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Walker 1990, p. 178.

- ^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. London: Columbia University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-231-51133-9.

- ^ Ghaziyan, Alvard (1984). "Զորավար Անդրանիկը որպես վիպա-հերոսական կերպար [General Andranik as a heroic character]" (in Armenian). Yerevan: Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Armenian National Academy of Sciences: 25–26. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Cite error: There are <ref group=upper-alpha> tags or {{efn-ua}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=upper-alpha}} template or {{notelist-ua}} template (see the help page).